Why is Ukraine losing ground? Deep analysis of military problems in 2025

“A small Soviet army cannot defeat a big Soviet army.” Once a cautionary tale, this phrase now rings prophetic. Of course, calling Ukraine’s army a “small Soviet army” oversimplifies the issue – neither Russia’s nor Ukrainian military is truly Soviet in the broad sense, but both have inherited the Soviet military’s systemic flaws.

For Ukraine, decades of neglect, underfunding, lack of military prestige, and compounding socio-economic problems have exacerbated these problems. Only a large-scale demanding society-wide mobilization has laid these issues bare.

As the war dragged on, minor issues in 2022 became glaring problems by 2025. Ukraine’s professional military core eroded, replaced by mobilized teachers, drivers, farmers, and IT workers. The military’s rapid expansion brought problems initially dismissed as “growing pains.” Three years later, these issues expose systemic failures to adapt, not mere growing pains.

A recent damning report on the 155th Anne of Kyiv Brigade exposes deep underlying issues in Ukraine’s military. Despite receiving training in France, the brigade allegedly suffered from high AWOL rates and inadequate initial preparation. It was fragmented and attached to other frontline units — symptomatic of broader systemic problems — ultimately leading to severe underperformance.

These demand attention. Blaming everything on a lack of Western weapons is simplistic and misleading — the brigade was trained in France and wielded Western arms.

Ukraine’s major manpower issues are often misread as mere unwillingness to fight, assuming frontline reluctance stems from a lack of will. Such oversimplification ignores critical structural problems.

Honest discussion about these issues is essential, without downplaying or ignoring their existence. History shows existential, conventional, and industrial-scale wars like this require drafts and mobilization. World War II proved large wars can’t be won by motivated volunteers alone: success depends on the state efficiently generating and deploying mobilized resources.

When undermanned brigades lose positions, it’s not always due to insufficient recruitment. Poor organizational decisions, such as funneling new draftees into new units rather than reinforcing depleted, veteran brigades, are often to blame. The window of opportunity to address these identified issues is closing fast – inaction is not an option.

Key critical issues for Ukraine’s army

1. Mobilization setbacks and infantry shortages

The story of Ukraine’s military recruitment has dramatically changed. In 2022, when Russia first invaded, hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians rushed to volunteer, eager to defend their homeland. But by 2024, the situation has reversed: more people are trying to avoid military service than are willingly joining up.

This shift isn’t surprising when we look at history. During major wars like World War I and World War II, countries fighting for survival often had to force citizens to join the military. Ukraine faces a similar challenge today. However, its government spent too much time trying to please both sides – avoiding unpopular decisions about military recruitment while still trying to meet the army’s growing need for soldiers.

Ukraine faced a growing shortage of combat soldiers in 2024. While its forces pushed into Kursk and created new military units, finding people to fill infantry roles became increasingly difficult. New recruits tried to avoid combat positions, worried about three main issues: commanders who didn’t value soldiers’ lives, little chance for rest from the frontlines, and poor planning.

Many chose to serve in support roles instead. While doctors, supply drivers, helicopter crews, drone teams, analysts, tech experts, communications staff, and military planners are vital to modern warfare, one fact hasn’t changed: you need infantry troops on the ground to control territory. Even the best defensive positions are worthless if there aren’t soldiers there to defend them.

The harsh reality of infantry combat can’t be ignored: the longer a soldier serves on the front line, the less likely they are to come home whole – or at all. For many Ukrainians who volunteered in 2022, their service has stretched into three years with few ways out of combat roles. Their options are grim: serious injury, death, desertion, or transfer to another position.

While Ukraine’s losses are much lower than Russia’s, especially when comparing the size of both countries, infantry soldiers still face terrifying odds. And “casualties” means more than just deaths. It includes life-changing injuries – lost limbs, blindness, severe mental trauma, or permanent brain damage. Some soldiers, exhausted from endless combat with no breaks, choose to desert rather than continue fighting.

In today’s war, where artillery and FPV drone strikes dominate the battlefield, infantry soldiers often face a brutal task: to draw enemy fire and absorb drone attacks, trying to survive from one fight to the next. It’s a devastating role that breaks both body and spirit.

Russian infantry face similar dangers, but with a few more escape routes. If they joined through volunteer units, they can leave when their contracts end. That’s not true for their regular soldiers – mobilization laws keep them locked in indefinitely. Meanwhile, Ukrainian infantry have even fewer options – one year of combat duty stretches into two, then three, with no end in sight.

The crisis runs deeper than just infantry shortages. When battalions desperately need foot soldiers, they start pulling people from crucial support roles – mortar crews, medical teams, and drone operators all get reassigned to the front lines. This creates a deadly domino effect: support units get hollowed out, while untrained soldiers face enemy fire. These reassigned troops, lacking basic infantry skills and combat experience, face a brutal – often fatal – learning curve.

This practice also sabotages recruitment efforts. When the army advertises positions for FPV or IFV operators, potential recruits are skeptical. They’ve seen too many specialists end up as basic riflemen shortly after completing their technical training.

Some observers – especially those amplifying Russian propaganda – jump to a harsh conclusion: Ukrainians’ recruitment struggles mean they lack the will to defend their homeland and thus deserve defeat. This misses a crucial historical truth: no nation can win a grinding conventional war of attrition through volunteers alone.

History proves this point. Both the Soviet Union and the United States had to draft large portions of their populations during World War II. Today’s conflict is no different – the scale of conventional warfare demands mass mobilization, not just willing volunteers.

Ukraine’s military draft has become deeply unfair. While wealthy and well-connected people often find ways to avoid service, the system targets society’s most vulnerable: the poor and those with health problems, including many battling alcoholism.

This creates a dangerous illusion. A unit’s paperwork might show 50 new recruits, but reality tells a different story. Many of these draftees have serious health issues, mental health problems, or substance dependencies. Instead of strengthening Ukraine’s fighting force, these recruits often drain resources while creating a false picture of military readiness. Units appear fully staffed on paper but lack real combat capability.

This broken system does more than just waste resources – it tears at society’s fabric. The war’s burden falls heaviest on those who already have the least, while the privileged remain safely distant from the fighting. This obvious inequality is destroying public support for the war effort.

Ukraine’s broken recruitment system reflects both current mismanagement and decades of deeper problems. While today’s government shares blame for avoiding tough decisions about military staffing, the roots of this crisis run much deeper.

For thirty years after independence, Ukraine’s leaders failed to build a system that could support wartime mobilization. This failure stemmed partly from a widespread belief that large-scale wars were history’s relics – something for textbooks, not modern reality. Meanwhile, Russian agents worked to weaken Ukraine from within, exploiting these gaps in military readiness.

The contrast with Russia is telling. Russia’s authoritarian system produces more reliable recruitment numbers through brutal repression. Any public resistance is quickly crushed, leaving only brief complaints on social media that are soon silenced. Ukraine, operating as a democracy, tries to work within legal boundaries – but its laws aren’t suited for wartime and aren’t properly enforced.

These problems aren’t impossible to fix. But after decades of neglect, solutions don’t come easy. What’s most damaging is the lack of urgency in making real changes. This has led many Ukrainians to question whether their leaders truly want victory or are just managing the ongoing crisis. Public trust in both political and military leadership has crumbled as a result.

The math is straightforward: adding 80,000 infantry troops could transform Ukraine’s frontline situation, either halting Russian advances or dramatically raising their costs, making every meter of captured territory unsustainable. This force – equivalent to 130 new battalions or bringing 200 existing ones to full strength – could either stop Russian advances or make their territorial gains too costly to hold.

Western observers often scoff at Ukraine’s recruitment struggles. They see a country with millions of men aged 24-55 and ask: how can finding 80,000 soldiers be so hard? This criticism paints Ukraine’s government as simply unwilling to take tough steps toward victory.

Ukraine’s response to this criticism has merit: they lack the weapons and equipment to properly arm such numbers. Sending poorly equipped soldiers to the front lines could backfire, leading to heavy losses without meaningful gains.

Yet this creates a dangerous cycle. Ukraine can’t control what weapons the West provides, but waiting for perfect conditions before expanding its forces is a risky gamble.

If Ukraine delays mobilization while waiting for Western equipment that may never arrive, it risks total defeat. The consequences would reach far beyond Ukraine’s borders – but by then, Ukraine might no longer exist as an independent nation.

2. Organizational and structural failures

Ukrainian forces face a serious command problem above the brigade level. This weakness has deep historical roots. Since gaining independence in 1991, Ukraine kept downsizing its military, chasing the idea of a “small but professional army” to save money. As part of these cuts, they eliminated larger military formations like corps and divisions.

The brigade became Ukraine’s highest tactical army unit. This seemed reasonable during peacetime but created a critical gap in leadership experience. Without large formations to manage, the military rarely conducted the kind of major exercises needed to train officers in coordinating multiple brigades or battalions.

When Russia launched its full-scale invasion, these past decisions came back to haunt Ukraine. Even when experienced officers were available, they couldn’t be used effectively – the military’s structure simply stopped at the brigade level.

This left Ukraine struggling to coordinate the kind of large-scale operations needed in a major war.

Ukraine has tried to patch its command structure gaps using temporary formations: OTU (Operational-Tactical Group) and OSUV (Operational-Strategic Group). These are stopgap measures meant to replace proper divisions and corps, but they come with serious flaws.

Officers in these temporary commands rotate frequently, creating an unstable chain of command. This constant turnover has real consequences: commanders don’t develop the deep understanding of their units that permanent leadership provides. More importantly, these temporary leaders don’t face the same accountability as permanent division or corps commanders – they know they’ll soon move on to different roles.

This fractured command system creates chaos on the battlefield. Instead of keeping brigades together as complete fighting units, the military often splits them up, sending individual battalions to different areas. The result is like a poorly assembled puzzle: brigades end up containing battalions from various other units, all operating under temporary OTU commanders.

These temporary OTU commanders then report to OSUV leaders who barely know the units under their control. They might understand what each brigade is supposed to look like on paper, but they lack real knowledge about the units’ actual capabilities, internal problems, or limitations.

This setup makes effective military planning nearly impossible. How can commanders make good decisions when they don’t truly know their own forces?

3. False reporting and lack of accountability

This broken command system is just one piece of a larger problem. Both Ukrainian and Russian militaries suffer from a toxic culture of dishonest reporting up the chain of command.

Officers learn a harsh lesson: admitting problems leads to punishment, so it’s safer to pretend everything is fine – even when units are falling apart.

Consider how this plays out: when a unit doesn’t have enough soldiers, regulations say it’s the brigade commander’s fault. Yet these commanders have no real power over recruitment – that’s controlled by completely different departments. Caught in this trap, senior officers often approve missions they know can’t succeed rather than risk being blamed for staffing problems they can’t fix.

Those who do speak up about troop shortages or supply problems quickly lose their positions, replaced by officers who will simply nod and agree to impossible orders. The cost of this broken system is paid in blood: units are sent into battles they cannot win, leading to needless deaths and mission failures that could have been prevented.

This culture of false reporting creates deadly situations on the battlefield. For example: when a position is lost, senior officers often don’t report it. They hope they can quickly retake the ground themselves, so they see no need to admit losing it in the first place.

This deception puts other units in extreme danger. Without knowing their neighbors have lost ground, units don’t realize their flank is exposed until it’s too late. Russian forces exploit these gaps, pushing deeper behind Ukrainian lines and attacking unsuspecting units from behind or from the sides. Caught by surprise, these units often can’t mount an effective defense.

False reporting and lack of accountability feed each other, creating a system where no one wants to make decisions. This becomes deadly when units face crisis situations – like being partially surrounded with their supply lines cut.

A perfect example: when a unit needs to retreat. Instead of making a quick tactical decision, the command chain freezes up:

- The battalion commander, afraid to take responsibility, passes the choice up to the brigade commander.

- The brigade commander does the same, pushing it to the temporary OTU leadership.

- The OTU sends it to OSUV.

- The decision keeps climbing higher, eventually reaching the commander-in-chief himself.

What should be a quick battlefield decision turns into a bureaucratic nightmare, with every level of command involved. By the time a decision finally comes, it’s often too late.

This broken system is so predictable that frontline units already know what to expect: even in desperate situations, they’ll likely be ordered to hold position until it’s too late. The command chain’s paralysis leads to needless deaths.

Some soldiers, seeing this pattern, choose to survive rather than wait for orders that may never come – they retreat without permission. This creates a new cycle of deception: officers, trying to protect their own positions, falsely report that everything is under control. They hope to either get troops back in position or hide the situation from their superiors.

The final twist is bitter: those soldiers who retreated to save their lives often become scapegoats. They’re blamed for the entire sector’s collapse and branded as cowards who abandoned their duty.

4. The West and the perception of betrayal

Morale has been damaged by more than just internal problems. The war’s early days in 2022 brought real hope – NATO and Western countries united against a common threat in ways not seen for decades. Putin’s invasion looked like a massive mistake, as he hadn’t expected such a strong, coordinated Western response.

But by 2023 and 2024, this unity began to crack. Putin’s original calculation – that the West’s support would eventually fracture – proved more accurate than initially thought. It just took longer to happen than he expected.

By 2023, cracks in Western support became impossible to ignore. The failed counteroffensive exposed painful truths: crucial weapons like ATACMS missiles arrived too late, after the operation had already failed. Western backing began to waver just as Ukraine needed it most.

The situation worsened in 2024. While Ukrainian forces fought desperately to hold Avdiivka, US Republicans blocked vital aid in Congress. Western politicians and experts began openly discussing whether Ukraine should accept peace at any cost – essentially suggesting Ukraine give up territory to end the war. For Ukrainians fighting for survival, these debates felt like more than betrayal.

History shows why this matters so much. Foreign support often decides the fate of nations fighting larger enemies.The American Revolution succeeded with the help of French aid to the Continental Army. The Soviet Union defeated Nazi Germany with crucial help from the US Lend-Lease program. Ukraine’s fight is no different – it needs steady Western support to survive.

Instead, delayed aid and uncertain backing have shaken Ukrainian society’s confidence in both victory and their Western allies.

Ukrainians are being forced to rethink their relationship with the West. The evidence is troubling: despite having an economy ten times larger than Russia’s, Western nations haven’t ramped up military production to meet wartime needs. Their decision-making remains slow, NATO membership stays out of reach, and promises remain vague.

A bitter question is emerging: Is Ukraine meant to be just a buffer state – a bloody frontier between the EU and Russia’s authoritarian regime? Are Ukrainians expected to endure endless war and economic hardship while Europe contributes minimal resources to its own defense, hiding behind American protection?

Western leaders send mixed messages. While European countries provide some aid, they fail to use their massive economic, demographic, and financial advantages over Russia. Their lack of political unity hands Moscow the advantage. This raises an uncomfortable question for many Ukrainians: Why are they expected to show constant gratitude when Europe seems more willing to watch Ukraine bleed than to slightly increase its defense spending and provide more substantial support?

These doubts create fertile ground for conspiracy theories – some homegrown, others planted by Russian operatives looking to exploit Ukrainian frustration.

This criticism of Western support reflects a growing frustration in Ukrainian society. More and more Ukrainians are facing a harsh choice: should they move their families to safety abroad rather than continue hoping for adequate Western backing?

While these feelings stem from despair and a deep sense of unfairness, they have real impact. They shape how Ukrainians view their future – or whether they believe they have one at all.

Help us make more articles like these — become a patron.

5. Failed communication and unclear goals

“Truth is the first casualty of war,” wrote Aeschylus, the Greek tragedian and war veteran, over 2,500 years ago. His observation remains accurate today – propaganda and deception still shape battles by influencing how people think and feel about the war.

When Russia first invaded, Ukraine’s use of inspiring stories and somewhat inflated victories served a vital purpose. At a time when most experts predicted Kyiv would fall within days or weeks, these narratives gave people hope to keep fighting against overwhelming odds. They helped combat despair both inside Ukraine and abroad.

In this light, Ukraine’s use of propaganda wasn’t just understandable – it was essential for survival. Every army and nation does the same in similar circumstances.

That being said, propaganda is also a dangerous tool that can turn against its creators. Putin himself fell into this trap, becoming a victim of his own lies. His propaganda machine convinced him that Russian forces could capture Kyiv in days – a delusion that led to one of his biggest strategic blunders.

Ukraine faced similar problems with its own propaganda. Before the 2023 counteroffensive, official messages painted Russian forces as weak and disorganized, unable to defend their positions effectively. Past victories – in Kyiv, Sumy, Chernihiv, Kharkiv, Mykolaiv, and Kherson oblasts – were used to support this story. But this optimistic narrative would soon backfire.

Both Ukrainian and Western analysts dismissed Russia’s mobilization efforts as failures that wouldn’t make a real difference. This fed a dangerous optimism about the upcoming counteroffensive – some even predicted it would end the war and push Russian forces out of Crimea.

Reality proved very different. When these ambitious goals proved impossible, the narrative had to change. Leaders started talking about capturing Tokmak instead – a much more modest objective.

When Tokmak also proved unreachable, the story changed again. Officials now claimed success by pointing to attacks on Russia’s Black Sea Fleet. But this raised eyebrows – these naval drone strikes had little connection to the ground offensive that had just failed.

This moment marked a turning point in Western support.

What started with hopes of quick Ukrainian victory now looked like a grinding war of attrition – exactly the kind of fight Russia had been preparing for since its “partial mobilization” in 2022.

Only then did many in Ukraine and the West begin to grasp the real situation: this would be a long, grinding war. It would test willpower, economic strength, and political unity – areas where Russia has historically proved resilient.

Yet the same mistakes were repeated with Avdiivka. At first, officials portrayed it as an impregnable fortress that would wear down Russian attacks. When the situation worsened, they insisted everything was “under control.” Reality proved different: Ukrainian forces eventually had to retreat under heavy pressure.

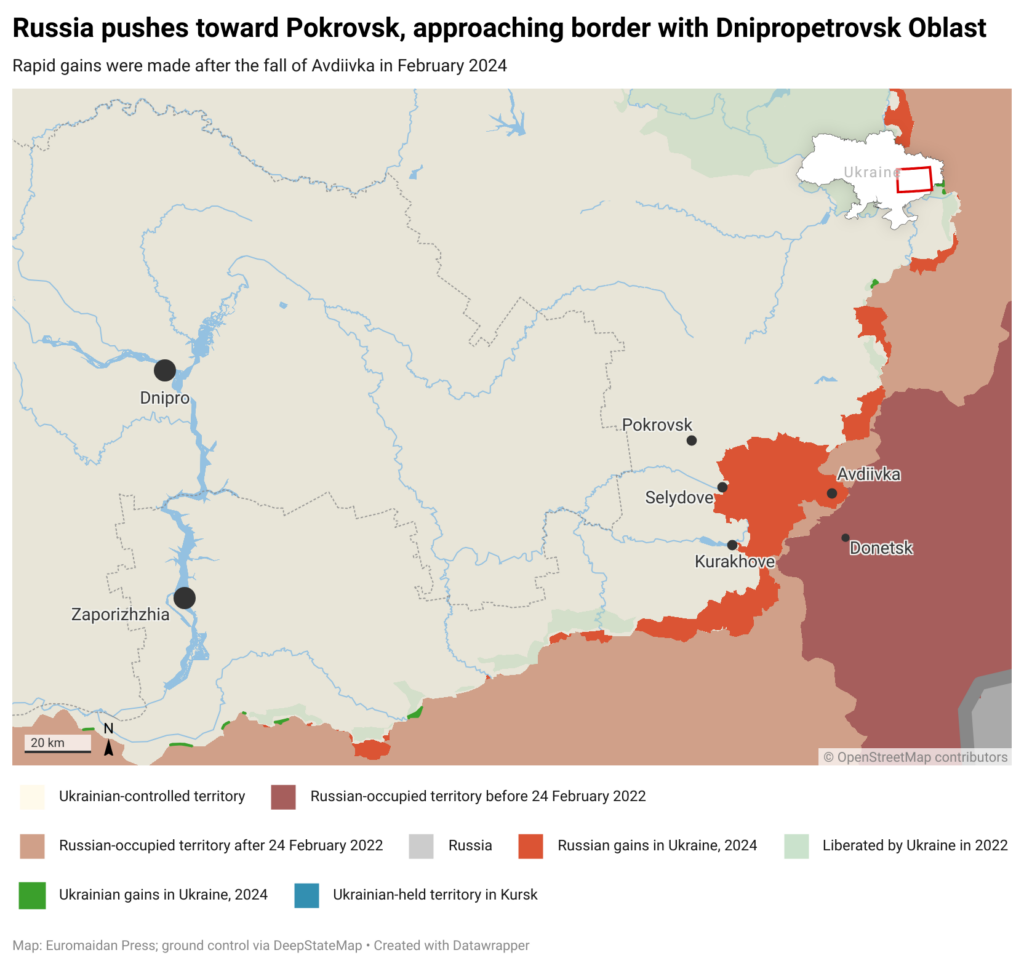

Predictably, the fall of Avdiivka was downplayed. Some analysts and commentators in both Ukraine and the West framed it as a tactical loss with little operational impact. Reality told a different story: the defensive lines behind the city were weak and understaffed. This allowed Russian forces to keep pushing forward – advancing toward Pokrovsk, taking Selydove and Kurakhove, and now threatening the Dnipropetrovsk Oblast.

The situation got worse when Vuhledar fell. This defensive strongpoint had held for years, but its collapse gave Russian forces new routes to push deeper into both Donetsk and Zaporizhzhia oblasts.

Some had sounded the alarm well before the crisis hit. Western analysts, Ukrainian reporters, and soldiers themselves raised red flags about Ukraine’s lack of manpower and weak fortifications months in advance. Back in December 2023, journalist Francis Farrell of the Kyiv Independent directly asked President Zelenskyy why defensive lines were behind schedule. Zelenskyy publicly insisted the fortifications were being strengthened.

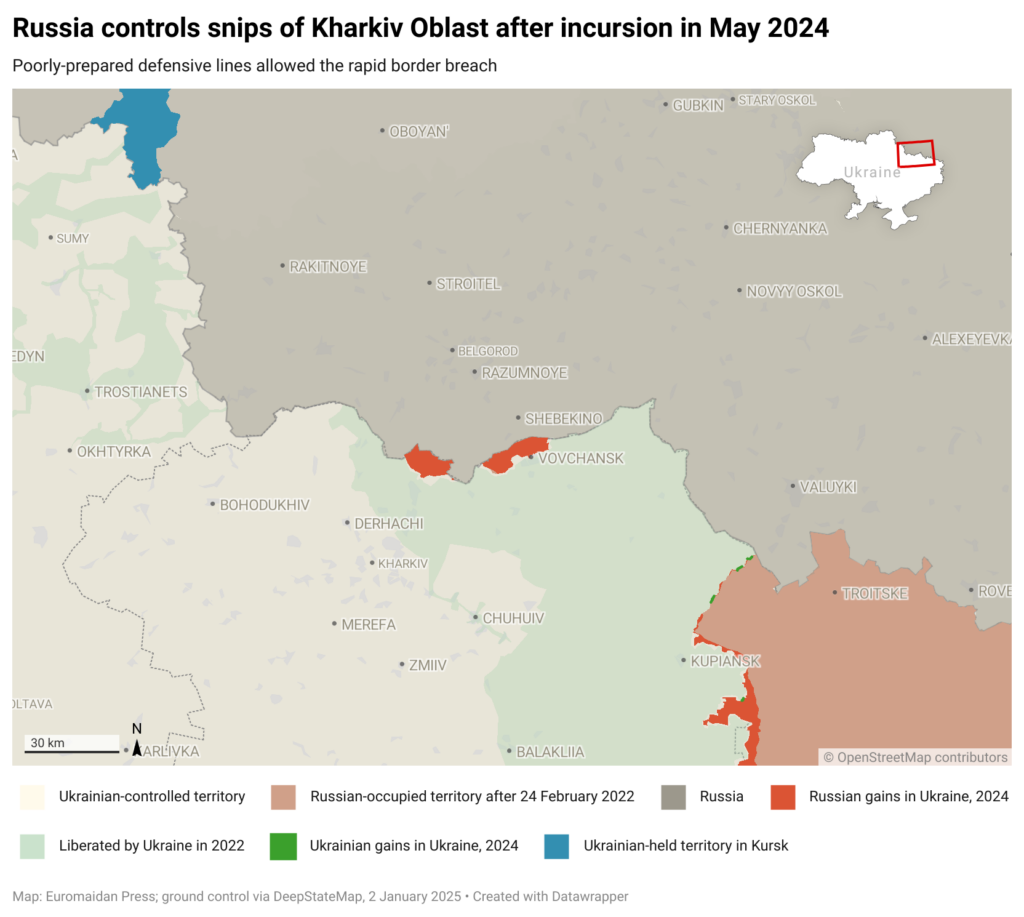

But when Russian troops surged back into Kharkiv oblast in May 2024, those defenses crumbled. Trenches were poorly built and often made little military sense. Earlier critics who highlighted these problems had been brushed off as “enemy propagandists” out to “undermine morale.”

In the end, it all came to a head at once for Ukraine: unprepared defenses, too few troops manning them, and a demoralized public realizing their leaders had failed to fix critical issues after years of war and had misled them about it. Ukraine was forced to grapple with this perfect storm.

Ukraine’s leaders also consistently tried to shift focus from domestic troubles to a lack of Western aid. They argued that all their major battlefield losses stemmed from allies not doing enough. This criticism was absolutely valid and needed to be voiced, but it was overemphasized to the point of overshadowing internal issues.

At first, the arrival of Leopard and Abrams tanks was touted as a potential game-changer. When their impact fell short of hopes, the focus turned to securing ATACMS missiles and F-16 jets. But even after Ukraine received these systems later and in fewer numbers than desired, the battlefront situation did not change dramatically. No miracles materialized.

To be clear, the Ukrainian government was absolutely right to obtain these advanced weapons and pressure the West for support. But their fundamental error was portraying foreign aid as the decisive key to victory while minimizing unresolved problems at home.

This messaging missed a chance to tackle critical domestic issues head-on. Worse, it further sapped faith that victory was possible, as the much-hyped new arms failed to meaningfully shift the war’s course. Ukrainians saw that none of the “wonder weapons” proved to be silver bullets.

As the war grinds on, a lack of clear, public war aims is sowing confusion about the endgame. Is Ukraine fighting to retake its 1991 borders or just to reach a ceasefire with Russia? Does enlisting now mean potentially unending military service that could drag on for a decade before these foggy goals are reached?

Meanwhile, an absence of visible urgency from Kyiv belies an existential fight for survival. For some, the horrific Bucha massacre is starting to feel like a remote event unlikely to be repeated. After all, if Ukrainian troops are holding the line far from the capital, decimating Russian forces and equipment, why the need for total mobilization?

By late 2024, the sense of relative normalcy wasn’t just a product of government messaging but also something society itself embraced.

To keep morale up, many journalists, analysts, and soldiers with large online followings often avoided uncomfortable truths. They self-censored, hoping others would resolve the issues. But the problems persisted, and Ukraine has now been jolted awake, faced with a mountain of challenges that feel overwhelming to many.

The once common refrain of “This isn’t the time to discuss problems” has shifted in many circles to: “It’s so dire it might be too late.”

However, it’s not too late. Although the window for achieving victory may be narrowing, there is still time to focus on avoiding defeat. Measures can still be taken to prevent further deterioration.

Solutions for Ukraine’s military problems

a) Reforming military leadership

Ukraine’s military leadership lies at the root of many of its problems, particularly the lack of decisive, forward-thinking generals. Much of the resistance to change comes from senior officers who rose through the ranks in the 1990s and 2000s, a time of military decline, corruption, downsizing, and stagnant careers. Most of these generals have little to no combat experience, having been promoted during peacetime rather than earning their stripes in battle.

However, there are positive examples to emulate, such as General Mykhailo Drapatyi. He started his combat career in 2014 as a battalion commander and steadily advanced to brigade commander, then head of an operational-tactical group, where he delivered results. He was recently promoted to Commander of the Ukrainian Ground Forces. This demonstrates the potential for competent leadership when merit takes precedence over seniority or political loyalty.

Ukraine’s national leaders must demonstrate a true commitment to the nation’s survival when appointing officers. This means replacing the Soviet-minded Commander-in-Chief Syrskyi, overhauling operational group leadership, and decisively, if gradually, replacing Soviet-era generals whose failures have often been ignored or even rewarded with promotions or new posts. Absent new leadership, reforms will fail as before.

That being said, replacing individuals, even high-ranking ones, is not enough on its own. Ukraine needs a system based on merit rather than connections or political loyalties. This demands establishing a framework that prioritizes measurable performance over subjective favoritism. Implementing a grading system supported by data-driven evaluations and key performance indicators would help ensure decisions are more objective and less influenced by bias.

Creating a perfectly objective system that consistently delivers ideal outcomes and selects the best candidates every time is nearly impossible. However, a well-designed framework can significantly curb rampant favoritism.

One of the most effective metrics for evaluating officers is operational efficiency – their ability to achieve objectives while minimizing the expenditure of resources. For example, if two officers operate under similar conditions, but one systematically completes the mission with minimal casualties while the other succeeds at the cost of entire platoons, the officer who achieved better outcomes with lower costs should clearly be prioritized for promotion.

It’s currently common for underperforming officers or those guilty of misconduct to be reassigned to equivalent or even higher positions within the military. This is not only unfair but deeply damaging, as it fosters a system of negative selection. Such practices must be eliminated as quickly as possible by ensuring that officers who fail to meet performance standards are excluded from promotions and, at a minimum, demoted during wartime – or dismissed entirely in peacetime.

For example, if four company commanders are competing for a single battalion commander position, only the most capable officer should be promoted. Those who repeatedly fail to advance after a few attempts should be retired from service, making way for better candidates.

Undoubtedly, it will take years to establish a new culture and system that consistently produces better military leaders. However, steps must be taken immediately, as nearly three years of stagnation have only emboldened incompetent officers, reinforcing the perception that they are neither accountable for rampant favoritism nor held responsible for repeated failures.

b) Elevating the conditions of frontline infantry

Serving in frontline infantry units should come with major perks that others don’t get. This includes set terms of service and guaranteed demobilization options when your time is up.

Some people are afraid that giving frontline soldiers a fixed end date could lead to a mass exodus with no one to replace them. But this is already happening, just in a different way. Thousands of soldiers are deserting or refusing to follow orders and go to the front.

In some units, this could be over 5-10% of the troops. That’s way riskier than letting infantry leave after a set time, like a year.

Still, war can’t just rely on volunteers. As I mentioned before, it needs required service, too, especially for infantry jobs that will never have enough volunteers. Ukraine’s current system for making sure people serve isn’t working well.

Trying to prosecute people for desertion or going AWOL takes too long and doesn’t fix the shortage of soldiers fast enough. It doesn’t help that Ukraine’s military court system is basically dead, having been effectively dismantled before the war.In fact, Ukraine still doesn’t have special military courts—they were abolished back in 2010 under President Yanukovych.

To address these challenges, Ukraine must fundamentally reform its military judicial system by creating an independent oversight body modeled after the US Army’s Office of the Inspector General. Such an institution could serve as a catalyst for meaningful change by investigating violations, handling complaints, monitoring compliance, and overseeing reform implementation.

It would help identify systemic issues, gather critical data, and provide analytical insights to measure progress and root out ineffective leadership among officers and non-commissioned officers.

In a promising step, Ukraine has already begun this process. In April 2024, the Ministry of Defense established a Military Ombudsman institution, with President Zelenskyy appointing Olha Reshetylova as the first Ombudsman. This role will safeguard military personnel’s rights, investigate violations, and implement measures to protect soldiers and their families. Yet, much will depend on the real powers of the role, which are yet to be established by a separate law.

Last, but not the least, soldiers must be assured that the state will not abandon them after they are wounded. While Veterans Affairs has taken some positive steps under new leadership, the damage done by their predecessors over two years of war has bred deep skepticism. Even well-intentioned efforts now face mounting distrust.

Many veterans are asking a critical question: Why sacrifice for a state that fails to care for its own? State leadership must improve its communication with the public and demonstrate that veteran care is a genuine priority – not just empty rhetoric.

Convincing the population that infantry service is meaningful and honorable will be no small feat, especially after three years of systematic mismanagement. The deeply ingrained image of Soviet-era generals recklessly sacrificing entire companies for minor tactical gains, just to report superficial successes, continues to cast a long shadow over public perception.

To overcome this stigma, Ukraine’s national leadership must demonstrate a genuine commitment to improving soldiers’ conditions and ensuring their survival and effectiveness. By implementing the previously mentioned reforms, they need to show that the military situation is evolving positively, not deteriorating further.

One proposed solution to reduce chaos on the frontline is to transition from the current reliance on temporary structures above the brigade level, to permanent unit frameworks like corps and division. Clearly defined roles, duties and responsibilities for commanders and staff, would improve continuity and cohesion. Commanders would have more time to develop familiarity with the units under their control, improving better coordination and decision-making.

c) Improving the army structure

Additionally, forming multiple separate assault battalions within division and corps structures could help address the issue of brigades being fragmented to reinforce other sectors of the frontline. These specialized battalions could be deployed as rapid-response units to stabilize critical areas without compromising the cohesion and operational integrity of existing brigades

Currently, reinforcements are often pulled from brigade-level units stationed in one region, such as southern Ukraine, and redeployed to entirely unfamiliar areas like Kursk. This practice not only places troops under unfamiliar officers but also leaves them unaware of neighboring units and their capabilities.

Divisions themselves can be formed around successful brigades and units, such as the 3rd Assault Brigade, which could serve as the backbone structure of a newly established division. This approach would allow the division to inherit the brigade’s culture, combat practices, and organizational methods – scaling them across a larger force.

By building divisions on proven brigades, Ukraine can create a framework with operational consistency. This model also provides a structured pathway for career advancement, rewarding officers who demonstrated exceptional performance at commanding companies, battalions, and supporting units — such as logistics, intelligence, and artillery. Experienced officers and NCOs from these brigades can be promoted within the division, enabling them to scale their expertise without being transferred to unfamiliar units.

This also means that Ukraine should immediately cease the formation of new brigades. The country not only lacks a sufficient pool of experienced commanders to effectively lead so many new brigades, but it also faces a shortage of Western countries willing to supply the necessary arms.

It makes little sense to continue establishing brigades that remain undermanned, underequipped, or both when the majority of existing brigades already face these challenges.

d) Transforming the training system

Ukraine’s military training system remains inconsistent despite some improvements. It spans from exceptional basic training with top-notch instructors to poorly run centers with inept staff providing little meaningful instruction.

While not universal, issues with training quality are fairly widespread. Multiple reports describe soldiers spending weeks in basic training idle or on non-combat tasks. In other cases, training is too short, cramming too many topics into insufficient time to learn.

Deploying inadequately trained personnel, especially those fresh out of abbreviated training, not only weakens battlefield units but also saps public morale. It fuels perceptions that all soldiers are poorly prepared and doomed to rapid frontline death.

Swift, thorough investigation of these issues is critical. A well-functioning institution like the proposed Office of the Inspector General should have the authority to promptly launch internal inquiries.

Their goal: determine if failures stem from negligence, lack of resources, incompetence, or even criminal conduct.

Better collaboration with military-focused foundations and organizations such as ComeBackAlive can improve Ukraine’s military effectiveness. These organizations already support crucial initiatives, such as data collection training program analysis. Currently, the Ukrainian military lacks a streamlined data-gathering framework, relying instead on excessive bureaucratic paperwork.

A modernized, electronic system for collecting and assessing data – one that can be quickly updated with real-time feedback from frontline brigades – is critically needed.

Ukraine already has promising examples of digital transformation. The Army+ application has streamlined personnel transfers between units, reducing what previously took months of paperwork to a process now completed within days. Soldiers can now submit transfer requests through the app almost instantly, significantly cutting bureaucratic delays and receiving widespread positive feedback from servicemembers.

Many brigades have independently developed training courses to address the reality that most incoming soldiers arrive unprepared for combat. These effective, ground-tested training practices should be systematically evaluated and then scaled up across the military. There is potential to create unified training programs at the division or corps level, which could complement existing training centers and provide more standardized preparation for soldiers.

Summary

This is a by no means exhaustive list illustrating that Ukraine’s systemic issues can’t be fixed with simple solutions. The critical first step is openly acknowledging these deep flaws exist. To defeat Russia and secure lasting peace, Ukraine must confront the problems undermining its national defense.

Discussions should focus on practical reforms, with national leaders treating constructive criticism as an urgent call to action, not an attempt to discredit the government. At the same time, critics must stay professional, aiming to improve governance, not opportunistically weaken wartime leadership.

Overcoming decades of mismanagement under the extreme pressures of war is a daunting task. But the alternative – defeat, collapse, instability, disintegration – is far harsher. Failure is not an option.

Russia’s gains have come at an enormous cost in lives, equipment, and long-term damage to its economy and demographics. Yet Moscow still pursues its objectives doggedly, and therefore the threat must be taken seriously. The current costs of war are insufficient to force Russia to withdraw. That is why sustained economic pressure on the Kremlin and continued weapons deliveries to Ukraine are vital to make the price of aggression unbearably steep.

Ukraine’s internal problems should not dissuade the West from maintaining its support. However, Ukraine’s leadership must also demonstrate through decisive action that this is an existential fight.

In areas where Ukrainian forces have superior training, coordination, planning, and Western-supplied firepower, Russian assaults are decimated. Making such successes the norm rather than isolated cases is crucial.

Strong leadership, effective training, a proper mobilization process, structural improvements, and consistent weapon supplies are the keys to victory. Without them, Russia will keep capturing Ukrainian land.

Related: