Ukraine, territory of sincerity: where we live despite it all

This essay was first published in the Swiss outlet Republic.ch under the title “Leben, trotzdem.” Euromaidan Press is publishing an English translation with the permission of the author.

I stand by the Literary House of Liechtenstein, gazing in amazement at a most unexpected sight. Sheep are frolicking in the meadow at the city center. They are merry as puppies, playfully jostling each other, and the joyful tinkling of their bells instantly transports me to the atmosphere of a Carpathian mountain pasture.

But no, here the mountains are different, the animals are different, the people are different—everything is different. “When I die, in my next life, I want to be a merry, carefree sheep in Liechtenstein,” I tell my Ukrainian colleagues, with whom I am touring Western Europe on a literary journey. “Or a cow in Switzerland,” says my publisher. “That sounds like a plan.”

In fact, I have only one life, and I want to live it in Ukraine. As a Ukrainian film director and writer, I often travel to other countries, but I generally live in Kyiv.

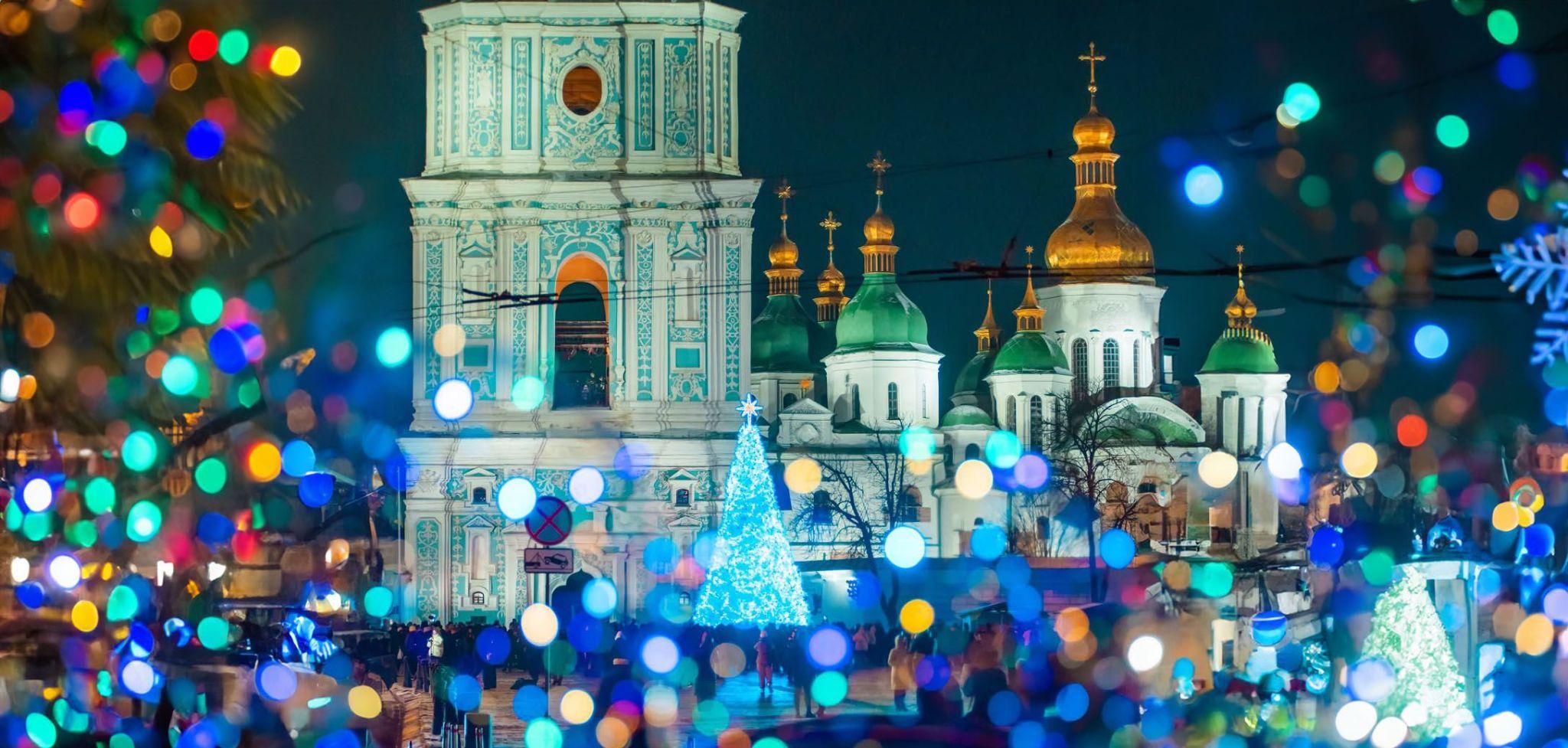

I love this city with unconditional love—it is my place of power and my Achilles’ heel at the same time, and therefore I cannot speak of it objectively. And yet I’ll risk saying that Kyiv, on the one hand, has its unique face, and on the other, even despite today’s situation of war, differs little from many other European capitals.

Indeed, it has its share of shortcomings, and beneath the applied makeup of modernity, the features of the repulsive post-Soviet legacy still occasionally peek through. But, despite everything, it is a very ancient, strong, and beautiful city. Now, it also pulses with a very vibrant special energy, which draws many people here like a magnet even during the war.

Before the start of the full-scale Russian invasion, there were over 3 million inhabitants here. Since then, the population in Kyiv and the Kyiv Oblast has grown by almost 50%. This is entirely logical, as many internally displaced persons from other regions of Ukraine have moved here, but there are also foreigners.

Though, of course, many people have left. Recently after my talk in Vienna, a very pleasant man approached me. He turned out to be an American who had lived in Kyiv for 13 years working as a teacher, but was forced to evacuate his family because of the Russian invasion.

He gifted me his book, which contains clever reflections on teaching and learning English. What’s interesting is that between the lines, the author’s sincere homesickness for Kyiv clearly emerges. I sympathize with those people who were forced to leave their familiar lives and now cannot take root in other countries. In our family’s case, the idea of possible emigration never even arose. But it’s always a question of a very difficult choice and responsibility for that choice.

Either way, I’m coming home once again. The trains between Poland and Ukraine, which I most often take, have their own special atmosphere: the majority of passengers are women and children, but you can almost always meet foreigners too—military personnel from the International Legion, journalists, or simply tourists who still come to the country where war continues.

This time too, I meet a distinguished gray-haired Canadian, whom I couldn’t help but ask about the Ukrainian flag on his jacket. It turned out he’s a biologist, but lately has been regularly coming to Ukraine to help with civilian evacuations and teach tactical medicine. Passing time at the station between trains, my new acquaintance and I eat kebabs while he tells me about his Arctic expeditions, life in South Africa, and his new love—Ukraine. Eventually we part to different train cars, but exchange contacts.

The train arrives in Kyiv at 5 AM, just as curfew ends. The city is still dark and quiet, but the sound of generators disrupts this harmony and reminds me that the Russians have lately been trying very persistently again to complicate civilian Ukrainians’ lives in winter. There’s no electricity in my building right now either, so I drag my suitcase up to the seventh floor, regretting that I asked my husband not to meet me.

At home everyone is sleeping, and I quietly make coffee on the gas stove while reading the morning news. Ukraine again won’t be invited to NATO, Russian drones have hit several energy infrastructure facilities in Ukraine, in the east the enemy is biting off new pieces of our land day by day, and we are all hanging in an anxious limbo, anxiously awaiting new scenarios from the reconfigured American political landscape…

“Oh, Mom, you’re home,” a sleepy teenager finally appears, followed by the rest of the cast—my husband and our cat. Everyone’s together again. My husband has been serving in Kyiv for over a year now and so lives at home, going to his army service as if to an office. This is something of a luxury compared to the times when he, a well-known Ukrainian writer, spent months on the front line.

In total, he has given four and a half years of his life to the army, and as someone who grew up with an aversion to any military experience (he had an Afghanistan war veteran in his family), he never planned anything like this for himself. But then again, who among us could have planned for this almost 11-year war?

We’re drinking coffee and unpacking travel souvenirs when suddenly, a siren starts wailing. To be honest, the sirens in Kyiv no longer force us to react to them in any way. First, not every one of them actually means an attack, and second, the capital is the best-protected of all Ukrainian cities.

Although, of course, no air defense system can guarantee 100% protection. Recently, one of these drones killed a teenage girl in Kyiv: it flew directly into her room, while her parents, whose room was on the other side, remained unharmed. There are many such stories in Ukraine, and I’ve grown thick-skinned. But this particular tragedy triggered me strongly: our apartment has the exact same layout.

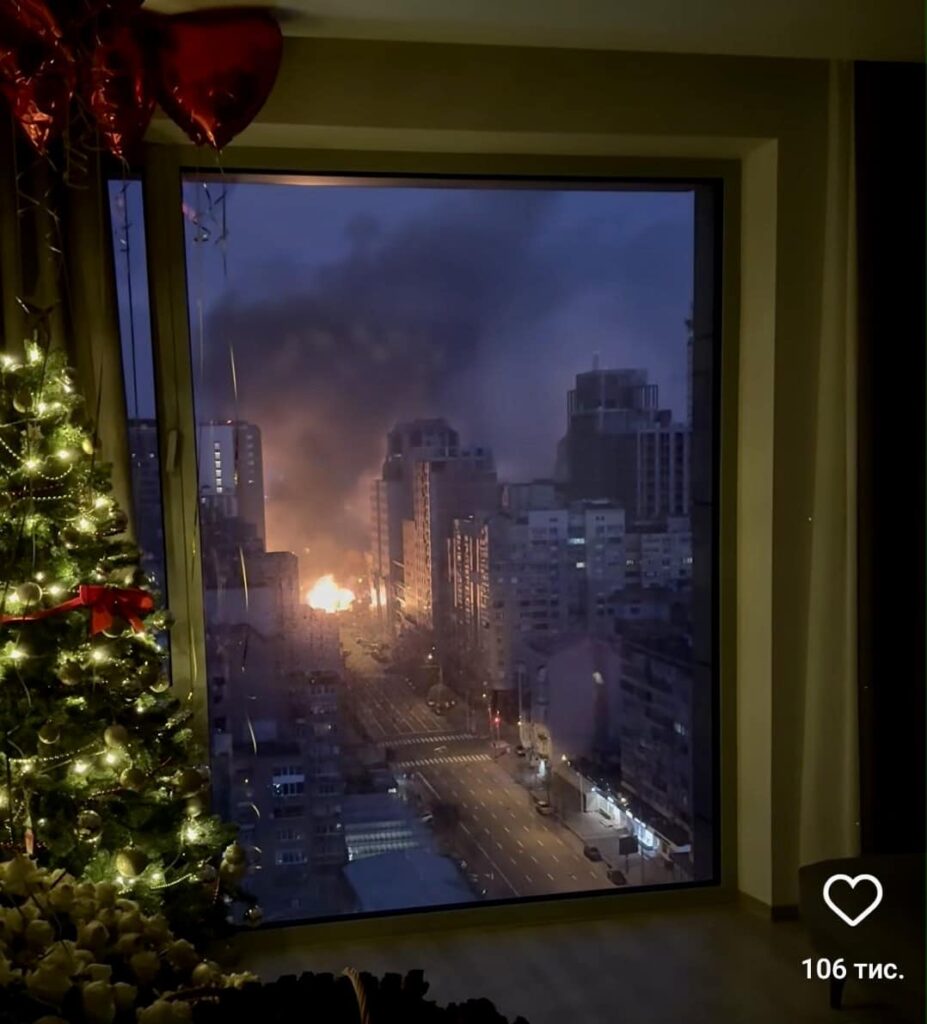

(Screenshot from video by Kateryna Moiseienko)

Still, this hasn’t made me and my 14-year-old son take air raid alerts more seriously. But while our self-preservation instincts have dulled and our fear response has completely disappeared, it’s the opposite for my husband. A year and a half ago, he went through a very traumatic experience at the front. He miraculously survived then and thought he’d emerged unscathed. But recently, his body has developed a new response: the sounds of explosions in Kyiv sometimes trigger panic attacks in my husband.

There are many people like him now, and there will be more. However, these traumas, invisible to others, often aren’t obvious, and Kyiv at first glance might appear like a rather carefree city. Restaurants and bars are full of people, theater life is more vibrant than ever, people actively go to cinemas, and new fashionable bookstores are opening in the city center. And on Saint Nicholas Day, a large Christmas tree was erected in Kyiv on the square in front of the 11th-century Saint Sophia Cathedral.

On the same day, rockets hit Zaporizhzhia, people burned in their cars and were killed and injured, including children, even a baby. The Christmas season in Ukraine has its own particular atmosphere.

And yet, the more missiles fall on our cities, the more we all find ourselves under the dark shadow of an uncertain future, the more desperately people need at least some moments of normalcy, rich cultural life, and so on. After all, there’s nothing new here—it’s all happened before in history.

Once in Paris, I visited an exhibition about the city in the early 20th century. I was deeply moved by the section devoted to World War I: here was a hall of testimonies about great tragedies, millions of lost lives, brilliant poets in trenches, and so forth. But then you enter the next hall, and there’s an exhibition about the flourishing cultural life that was thriving at the same time, just a bit further from the hell. How familiar…

Such things are even more striking when you travel now to frontline areas. In November, I visited several cities in southern Ukraine together with two other poets. The cities in this region are under constant shelling, with civilian casualties almost daily. But there, as in other threatened frontline areas, the halls are always full, and poets are sometimes received like rock stars. In Kherson, where the event organizers only allowed us to travel in bulletproof vests and helmets, and instructed us what to do in case of a drone attack, the meeting with readers was held secretly, without publicly announcing the place and time, in an underground shelter. But despite the morning hours on a workday, the hall was still full of people.

Of course, it’s not just love for the poetic word that brings people to such meetings. By and large, it’s people searching for kindred spirits. Especially in times of such immense uncertainty, which increasingly risk turning into collective depression.

The dark December days weigh heavily, and the year’s end always prompts us to draw various conclusions. Exactly a year ago, I wrote a Christmas poem that began with the words “Everyone is tired. To be honest, everyone is really tired.”

What can be said about this year, which has been significantly harder? Ukrainian society is exhausted and frightened by vague prospects, while the existing sharp rifts between people with different experiences wound us all.

For example, we’ve long been short of fighters at the front, and the tension that has formed between those serving in the military and those remaining in the rear has intensified greatly. If at the start of the invasion there were queues of volunteers at recruitment offices, now societal fatigue and disbelief that the collective West truly desires victory over Russia, along with the numbers of those killed and maimed at the front, have severely cooled the desire to fight among those who haven’t yet served.

The difference in experiences is felt even more strongly during my constant travels to various countries of the Western world. There are different people there, everything is different, and somewhere at the junction of our polar realities comes an understanding of the heterogeneity of the threads of fate that invisible Moirai spin for us all.

We Europeans are very different and face dissimilar challenges. Often, the well-fed don’t understand the hunger, the traumas of former colonies and former colonizers differ, and so on. But over the years of war, I’ve become a wise owl, and my personal feeling of resentment about these unequal rules of the game given at the start has dissipated. Unfortunately, however, my faith in the strength of the collective West has also faded.

Holding dialogues with Evil and trusting its promises is a dubious strategy, as any plot from world history or literature will tell you. Of course, I can understand the confusion, the fear of possible escalation, and the desire to distance oneself from someone else’s misfortune. As well as the fact that many are now ready to sacrifice Ukraine for the sake of postponing an open conflict with Russia. Still, the subtle art of double standards practiced by those we consider our allies has proved, for me personally, a greater trial than the open aggression of enemies.

The subtle art of double standards practiced by those we consider our allies has proved a greater trial than the open aggression of enemies.

Iryna Tsilyk

I remember when in summer, Ukraine’s largest children’s hospital, OHMATDYT in Kyiv, was deliberately struck by a Russian Kh-101 missile,experts thoroughly examined the recovered missile. Eventually, they found electronics from various Western companies in missiles of this type, including from the USA, China, Switzerland, Germany, and others. By and large, it’s long been official information that Russian weapons seized on the battlefield constantly contain large numbers of American and European parts and components. Well, it’s all just business, as they say. And this is just one fragment of this complex puzzle.

Look, here’s the UN Secretary-General, studiously ignoring the genocidal nature of Russia’s war in Ukraine as he warmly shakes Putin’s hand—snap, what a striking photo. And here, look at these other haunting images—from the opened prisons in Damascus, following the fall of Putin’s ally’s regime. Human skeletons wrapped in skin who spent 40 years in prison, raped women whose children were born in captivity and never saw daylight, fragments of human bodies not fully dissolved in acid.

Now I’m more certain than ever that such a modern death camp would have existed in my city if Putin’s dreamed-of blitzkrieg—”Kyiv in three days”—hadn’t failed. And the entire democratic liberal world would have maintained the same silence about these modern gulags, just as it “failed to notice” them in Syria or in other Ukrainian territories occupied by Russia.

And so it goes. But I don’t really want to peer too deep into this Pandora’s box. After all, if it weren’t for the Western allies and their help, Putin’s dream of completely swallowing Ukraine would likely have come true long ago. Still, I find myself longing for those times when, standing on Maidan during the Euromaidan Revolution, I could still believe wholeheartedly in concepts like honesty and honor.

By the way, in December we marked a particular anniversary—exactly 30 years ago, the Budapest Memorandum was signed, under which Ukraine was forced to relinquish its nuclear weapons in 1994. In exchange, we received a Memorandum from the USA, Great Britain, and the Russian Federation, who pledged to protect Ukraine’s sovereignty and integrity and “to seek immediate United Nations Security Council action to provide assistance to Ukraine if it becomes a victim of aggression.” Well, doesn’t all this sound like a bitter joke now?

That’s why I always return home and want to live only here. Paradoxically, amid endless hardships, revolutions, war, and a total sense of vulnerability, despite exhaustion, frustration with internal corruption scandals, and so on, I still feel that Ukraine is a territory of sincerity and struggle for justice for me.

Yes, there are many “buts” behind all this, and we shouldn’t gloss over or romanticize them, but nevertheless, as American historian Marci Shore recently put it in an interview,

“You just feel that you want to be here because something important is happening here. I think that today Ukraine is the most important place in the world, where our future is being defined.”

Marci Shore

…In Kyiv, I slip back into the rhythm of normal life. Or rather, normal-abnormal life, but we have no other. A few days before Christmas, Russia attacked my city with eight ballistic missiles. One person died, at least twelve were wounded. Also, one of the intercepted missiles fell on a large office complex, and the resulting explosion damaged the stained-glass windows of the neo-Gothic St. Nicholas Cathedral across the street.

Nevertheless, people quickly returned to their usual lives: amid sirens, attacks, and daily tragedies, we maintain our regular daily routines, go to work, send children to school, sometimes enjoy leisure time, and drink wine with friends (or antidepressants).

But you know all this from the news. Let me tell you something unexpected and bizarre. Recently, I learned that some Ukrainians, when going to bed at night, put a little dry dog food in their pajama pockets. Why? So that rescue dogs can find them more quickly under the rubble if need be. A useful life hack.

There’s something deeply moving about this image: here stands the average Ukrainian—perpetually sleep-deprived (oh yes) and irritated because of it. This person wants nothing more than a peaceful life. On one hand, they look hopefully at the rumors from all sides prophesying the coming resolution of this war. On the other hand, they stubbornly crave justice and won’t accept a bad peace, understanding that we’ll be deceived again.

And so even while disillusioned with everything, no longer allowing themselves to confidently say the word “victory” aloud, cursing everything in the world and especially their country’s government, losing their last remnants of faith, strength, and youth, these average Ukrainians—standing with weapons in hand, with donations for FPV drones for the front, with dog food in their pajama pockets, and so on—are very dear to me. And only here am I finally home.

Editor’s note. The opinions expressed in our Opinion section belong to their authors. Euromaidan Press’ editorial team may or may not share them.

Submit an opinion to Euromaidan Press

Related: