The collapse of Assad’s regime shows the limits of Russian airpower

After a decade-long civil war, Bashar al-Assad was firmly ensconced in Damascus — a far cry from the summer of 2012 and again in 2015, when policymakers, analysts, and pundits alike believed his rule was on the brink of collapse. The intervention of the Russian Air Force in the fall of 2015 saved the al-Assad regime.

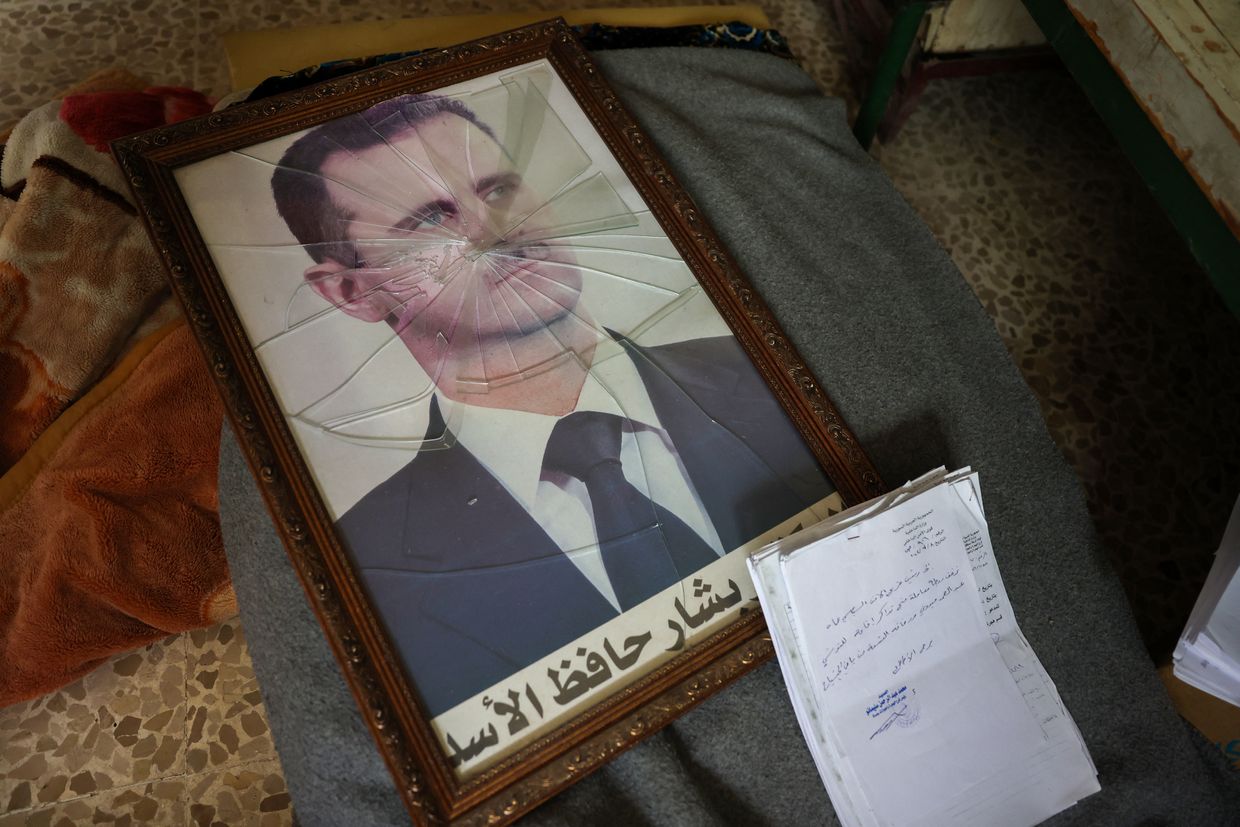

Yet, its sudden collapse on Dec. 7 highlights a key lesson: airpower can achieve tactical victories but not long-term strategic ones. This offers a glimmer of hope for Ukraine. Al-Assad lost because he couldn’t survive sanctions, and Russia’s bombing didn’t break the people’s resistance — two lessons with direct implications for Russia’s war in Ukraine.

Since the Arab uprisings of 2011, Syria has been the only case of a Soviet/Russian-provided military arsenal — originally designed to achieve strategic parity with Israel — being turned on its own population. Yet, by 2015, the Syrian government was at its weakest, unable to break a stalemate. The state had secured the north-south axis from the capital along its coastal spine, while the Kurds consolidated control over their territory. However, Aleppo was outside government control, and ISIS was on the offensive.

In May 2015, Secretary of State John Kerry visited Russia to restart negotiations. The stalemate of 2015 had set in, and this would have been the most opportune moment for the Syrian state to feel pressure to pursue a negotiated political resolution. But instead, Russia’s decision to intervene in fall 2015 ensured that al-Assad would not negotiate from a position of weakness. The Russian intervention was not about supporting al-Assad out of devotion to Syria’s president per se, but about dictating the outcome of a negotiated endgame, including a politically expedient way for al-Assad to step down on Russia’s terms.

The Russian air deployment was relatively small, consisting of just 28 aircraft and 20 helicopters. Yet, as Russia scholar Mark Galeotti noted, “Just by starting their Syrian operation, they essentially derailed large parts of U.S. foreign policy with about 30 aircraft.” The Russian force mainly included 12 Su-24s, 12 Su-25s, and 4 Su-34s, as well as six Mi-24 Hind helicopters, all designed for air-to-ground combat.

Some aircraft, like the Su-34, were newer models not in the Syrian inventory, illustrating another Russian goal: using Syria as a training ground for its revamped military. Russia also tested its first stealth fighter, the Su-57, in combat over Syria in February 2018. Additionally, from fall 2015 to summer 2016, Russia tested long-range Kalibr cruise missiles over Syria, ostensibly against ISIS targets.

Deploying the previously mentioned Russian aircraft stationed in Syria would have been more effective and accurate in targeting ISIS, not to mention cheaper than using costly cruise missiles. However, for Russian President Vladimir Putin, an air raid would not deliver the same political message. The range of the cruise missiles demonstrated to the U.S. and NATO Russia’s advances in military technology, which were more about Moscow’s tensions with the U.S. and NATO’s presence in the Baltics than about Syria.

The strategy of the Syrian state up to 2015 — and the Russian Air Force post-2015 — was to saturate insurgents with firepower from a distance, even if it meant risking air assets to deploy indiscriminate bombing campaigns to terrorize civilian populations in insurgent-held areas (such as with barrel bombs). However, the state lacked enough forces to garrison troops in every insurgent area to hold those regions, hence the need for the creation of the National Defense Forces and the importation of fighters from Iraq, Afghanistan, and Pakistan. While Russia deployed technical crews to maintain its aircraft, most of its ground forces came from mercenaries employed by Evro Polis, a company often associated with the Wagner Group.

It was at this juncture — when Damascus was mired in a hurting stalemate — that the intervention of Russia’s Air Force and renewed Iranian commitment allowed the state to eventually recapture lost territory, including Aleppo in December 2016 and many, though not all, remaining insurgent enclaves by 2022. This was enough to determine victory for al-Assad. It also explains the Russian hubris in believing its 2022 assault on Kyiv would be swift and decisive.

Russia’s air force intervention was a decisive factor in turning the momentum back to the Syrian state, culminating in al-Assad’s victory in Aleppo. By 2022, after a decade of civil war, the Syrian state — thanks to its allies — had essentially achieved a military victory, though its hold on certain territories remains tenuous. As of early 2022, the state controlled 75% of the country’s territory, including most urban centers along the north-south spine, while the eastern oil fields remained under the control of the U.S. and Kurdish allies.

This is the first lesson: with no access to oil and sanctions imposed on Syria, al-Assad didn’t realize how much the people were hurting economically and how indifferent they were to his regime’s survival.

The second lesson comes from the Blitz of London during World War II. Malcolm Gladwell, in “The Bomber Mafia,” writes, “It turns out that people were a lot tougher and more resilient than anyone expected. And it also turns out that maybe if you bomb another country day in and day out it doesn’t make the people you’re bombing give up and lose faith.”

Gladwell concludes, “More than a million buildings were damaged or destroyed. And it didn’t work!” The Blitz did not break the morale of the British people, nor did it break the morale of the Syrians, and it won’t break the morale of Ukrainians.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed in the op-ed section are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Kyiv Independent.