Russia’s military collapse by 2026: Ukraine’s intelligence assessment

Ukraine may be entering the final stages of its war with Russia, with the war potentially drawing to a close by the end of 2025 and early 2026, at least according to Kyrylo Budanov, head of Ukraine’s Directorate of Intelligence. Budanov shared this projection based on intelligence data during the annual Yalta European Strategy meeting, an international platform that puts together prominent Western and Ukrainian figures.

As the initial invasion has evolved into an attritional war, understanding the enemy’s will to fight, their resources, and their ability to replace losses becomes critical in order to calculate the trajectory of war. The specific numbers provided by Budanov and backed up by expert analyses provide factual substance to the discussion, making it more valuable for projecting accurate timelines.

Russian military production

Any attritional war ultimately becomes a test of societal endurance, war economics, diplomacy, and the ability to replace losses. As the war drags on, these problems intensify, pushing one side closer to a tipping point where continuing the war worsens their position. Military production and the capacity to replace losses are among the war’s tangible factors that can be calculated and projected well.

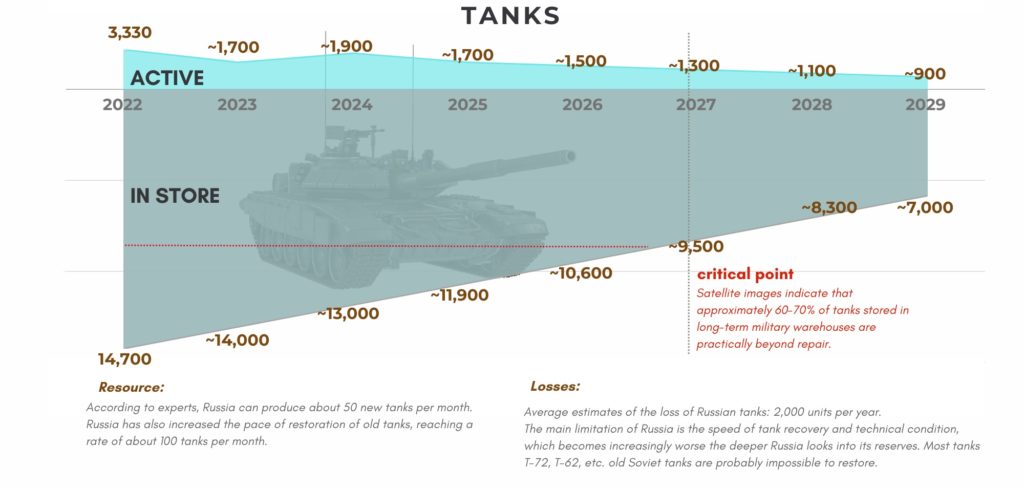

One notable point from Budanov’s conversation was Russia’s plan to produce 149 T-90M tanks in 2024.

At first look, according to data from the open-source intelligence project Warspotting, Russia has lost approximately 47 T-90M tanks this year – a number notably lower than projected production, which makes it tempting to assume that Russia’s tank production is keeping up with its battlefield losses

However, this is only a superficial assessment; the reality for Russia is far direr.

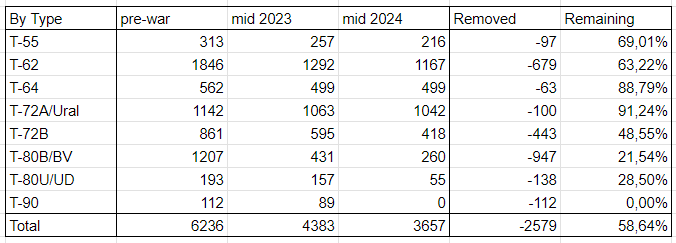

Russia has been heavily relying on refurbishing older tanks, such as the T-72, T-62, and T-55/54 models, from its Soviet-era stockpiles. Most of its current tank fleet on the battlefield is relying on tanks no longer in production.

While this has allowed Russia to preserve more advanced tanks like the T-90M, Russia’s Soviet reserves are depleting quickly, and the tank fleet is on a sharp decline.

OSINT analyst @Highmarsed, who tracks open-air storages and shares insights on X (formerly Twitter), provides a more detailed assessment. He reported that by 6 July 2024, Russia’s stock of T-55s had dropped by 31%, T-62s by 37%, and T-80Bs by 79%, with only 9% of T-72s removed from storage.

While these figures may not be exact, they provide a good idea about the rapid depletion of Russia’s tank reserves.

Additionally, OSINT analyst Naalsio, who tracks battlefield losses, estimates that by 4 October 2024, Russian forces had lost over 539 tanks and 1,830 vehicles in total (including tanks) in the Pokrovsk direction (formerly the Avdiivka direction) since 2023—numbers that far surpass Russia’s current tank production capacity.

Given that since the beginning of its full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Russia has lost over 3,000 tanks (information that can be independently confirmed by open-source projects such as Oryx or Warspotting) Russia has lost more tanks than it had in its entire prewar active-duty tank force, as well as and over 30% of its most advanced self-propelled artillery and multiple rocket launcher systems.

A report from senior analyst Dara Massicot, published by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, further details that Russia is expected to exhaust its stockpile of multiple Soviet-era military equipment by 2026.

There are also clear challenges in replacing Russia’s air force losses. Some older jet models are no longer in mass production, and the new jet production is less impressive. For example, Budanov noted that Russia plans to produce only 14 Su-57 fighters in 2024.

That being said, it’s not all bad news for Russia: its Iskander missile production, particularly the Iskander-M, has ramped up significantly. While Budanov didn’t specify exact numbers, this aligns with reports from the ground about Russia’s frequent use of these missiles.

This is a serious problem for Ukraine, as it cannot currently fully protect itself from these missiles. The limited number of Patriot systems cannot fully safeguard cities and the entire frontline. Additionally, ballistic missiles themselves are a problem for most air defense systems.

Mitigating this threat will require a multi-layered approach: increasing air-defense numbers, as well as detection and warning systems. This should go hand in hand with allowing Ukraine to strike across the border with Western weaponry and developing deep-strike capabilities to neutralize these missile storages at a distance.

Unfortunately, these factors largely depend on the West and its willingness to sustain investment in the war – something over which Ukraine has only limited control.

But can Russia expand its production further?

According to the same Carnegie Endowment report, Russia’s military equipment production, aside from drones, had plateaued as of early 2024. Further expansion is unlikely unless new factories are constructed or the government takes the significant risk of temporarily halting exports or shutting down production lines to retool and modernize existing facilities.

It’s important to note that we are now at the beginning of October 2024, and even if Russia were to begin constructing modern plants with all the necessary equipment and personnel, it would take well over a year to bring such production online. This means that any significant expansion wouldn’t be feasible before the second half of 2025

Currently, Russia is attempting to bridge the gap between its production capacity and frontline needs with the help of its foreign partners and allies.

According to Kyrylo Budanov, North Korea is Russia’s largest military partner in this regard, primarily due to the volume of artillery shell supplies. He noted that after a North Korean shipment arrives, combat intensifies within 8-9 days and this effect lasts for up to two weeks, showing a direct correlation between artillery shipments and combat intensity.

Given that North Korea has also been supplying Russia from its own stockpiles, it’s uncertain whether Pyongyang can significantly ramp up production to meet Russia’s demands. It’s also unclear how deeply North Korea is willing to draw from its own artillery reserves, especially when tensions in Korean Peninsula remain consistent

Domestic Ukrainian projects have had a significant, yet often overlooked, impact on the war effort

While Western technology receives much of the attention in political, diplomatic, and expert circles, the effect of Ukraine’s domestic production, development, and scaling of homegrown technology has been underestimated.

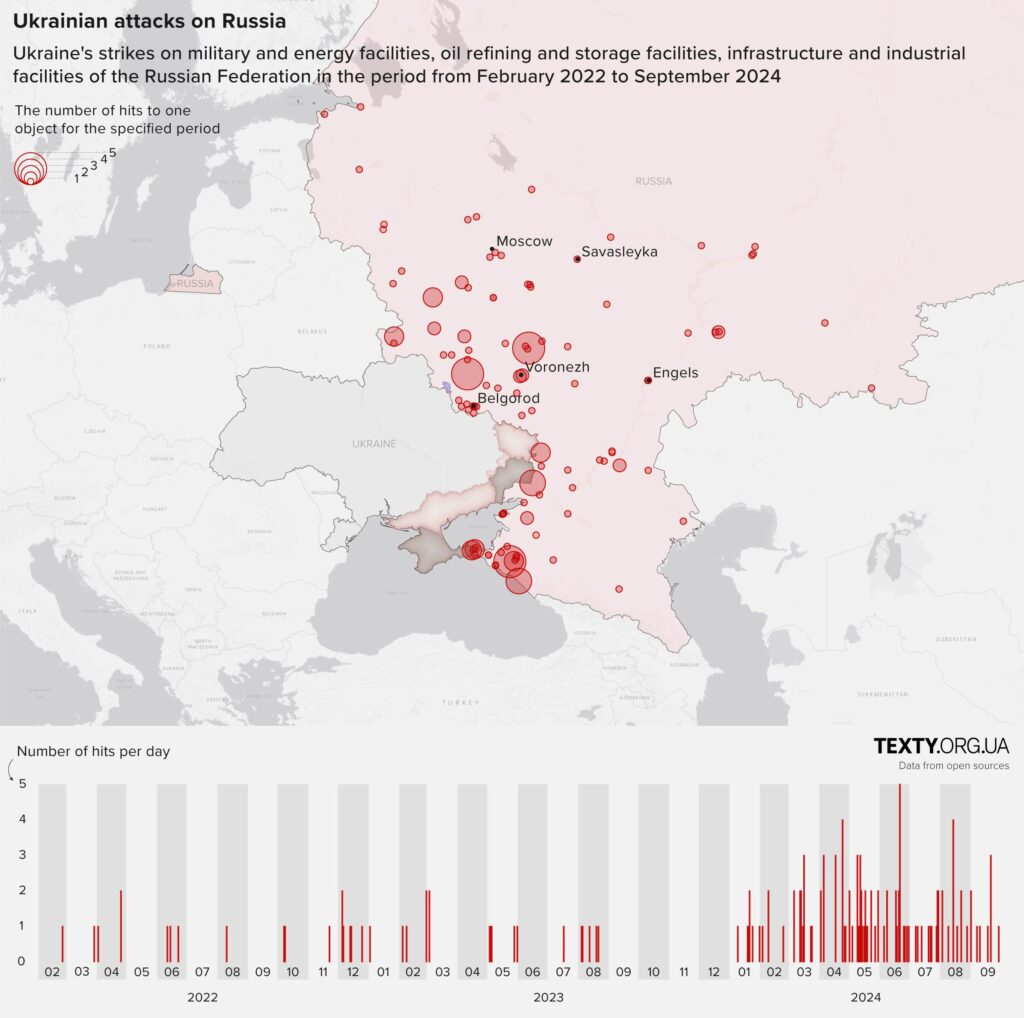

General Budanov explained the importance of Ukraine’s long-range drone strikes deep inside Russia, including Moscow. These strikes have shaken the confidence of the Russian people, undermining the belief that their leadership provides ultimate security and ensures Russia’s military might.

As the war progresses, more Russians from various social backgrounds are questioning why the war is reaching their homes and whether their leadership can truly preserve Russia’s pre-war status as a formidable military power capable of protecting its citizens.

But Ukraine’s successes aren’t limited to long-range drone strikes. Two other key innovations have also shaped the course of the war:

Unmanned Surface Vehicles (Sea Drones)

In the early stages of the invasion, when Ukraine’s already small fleet was unable to resist Russia’s Black Sea fleet, Russian naval dominance seemed unquestionable. That perception started rapidly to change with the successful destruction of the missile cruiser Moskva – the pride of Russia’s Black Sea fleet.

But that was only the beginning.

The introduction of domestically developed sea drones has since become Ukraine’s surprise weapon, rapidly evolving into a core naval weapon, and despite having a largely non-functional fleet, Ukraine has managed to destroy a quarter of Russia’s Black Sea Fleet.

More significantly, these drones have denied Russia’s navy the ability to operate freely. Ukrainian grain ships now sail much safer, as any attempt to impose a blockade or attack risks immediate and effective Ukrainian retaliation in the Black Sea. This capability has enabled Ukraine to protect its maritime interests while deterring Russian actions in the Black Sea.

The number of FPV drones on the battlefield has surged from just dozens to tens of thousands in under a year.

FPV Drones

The widespread use of FPV drones – small, racing-style drones costing under $1,000, has reshaped the battlefield. These drones are capable of targeting everything from armored vehicles to advancing infantry and reconnaissance drones and even helicopters.

During the artillery shortages of 2023 and early 2024, FPV drones became a crucial tool in the arsenal, often serving as the primary means to engage the enemy at longer distances, with some able to fly up to 20 kilometers using transmitter drones.

Through grassroots efforts, volunteer organizations, and some government assistance, Ukraine has managed to scale the production of drones and standardized munitions for them. While there remains a shortage of drones and a lack of sufficient state involvement in their procurement for military units, the number of drones on the battlefield has surged from just dozens to tens of thousands in under a year, making them an essential part of the war theater.

Investing in Ukraine’s domestic production and pursuing joint projects with Western countries could be one of the most effective paths forward. This approach can help to reduce the political risks and fallout associated with gaining permission to strike deep inside Russia with Western missiles – something Ukraine has already managed to achieve independently, without resulting in over exaggerated fears of nuclear missile launches.

A self-sufficient Ukraine is more beneficial to its partners, easing the political friction in the West over its own dwindling military supplies. This will help Ukraine to take an important role in a changing security and geopolitical environment, where it can serve as a key partner for Europe in the defense area. With its proven expertise and production capabilities, Ukraine will organically contribute to the Western defense efforts through collaborative projects.

It’s not just about the military

As General Budanov notes, Russian internal calculations suggest that if Russia doesn’t exit the war by the anticipated time frame, it will be unable to claim “superpower” status in the foreseeable future — at least 30 years. Instead, the most it can hope for is regional leadership.

Internal Russian analysis predicts Russia will lose its global status and only two superpowers will remain: the US and China.

Internal Russian analysis predicts only two superpowers will remain: the US and China, a scenario referred to as “The Rise of China” and “The Domination of America,” with no place for Russia on the global stage.

This projection isn’t driven solely by war production challenges but also by a deteriorating financial and economic situation, slowing growth, and expected setbacks.

Former French military intelligence officer Pierre-Marie Meunier, analyzing 2023 data from Russia’s Central Bank, highlights a sharp decline in Russian exports. Goods and services exports fell by 29% and 17%, respectively, from 2022 to 2023, while imports rose by 10% and 5%, resulting in a sharp drop of the trade surplus.

In September of 2024, Russia raised its key interest rate to 19%, with its inflation rates reaching over 7%

Meunier paints a grim picture: in a country where over half the population relies on state subsidies, where the poverty rate exceeded 13% in 2021 (even with far lower poverty thresholds than in the West), and where 62% of Russians lack savings or the means to afford more than basic necessities, Russia risks facing a long-term economic crisis reminiscent of the one that preceded the fall of the Soviet Union.

It’s fair to say that while sanctions haven’t stopped the war, they are slowly strangling Russia, making it increasingly difficult to manage the consequences of the war.

While sanctions haven’t stopped the war, they are slowly strangling Russia.

These mounting problems create potential grounds for future negotiations, which President Zelensky is aiming to leverage through the Peace Summit scheduled for November 2024, as he seeks a diplomatic resolution.

However, the timeline suggested by General Budanov might prove more realistic than the November talks, with the situation in Kursk playing an important factor.

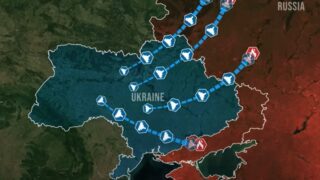

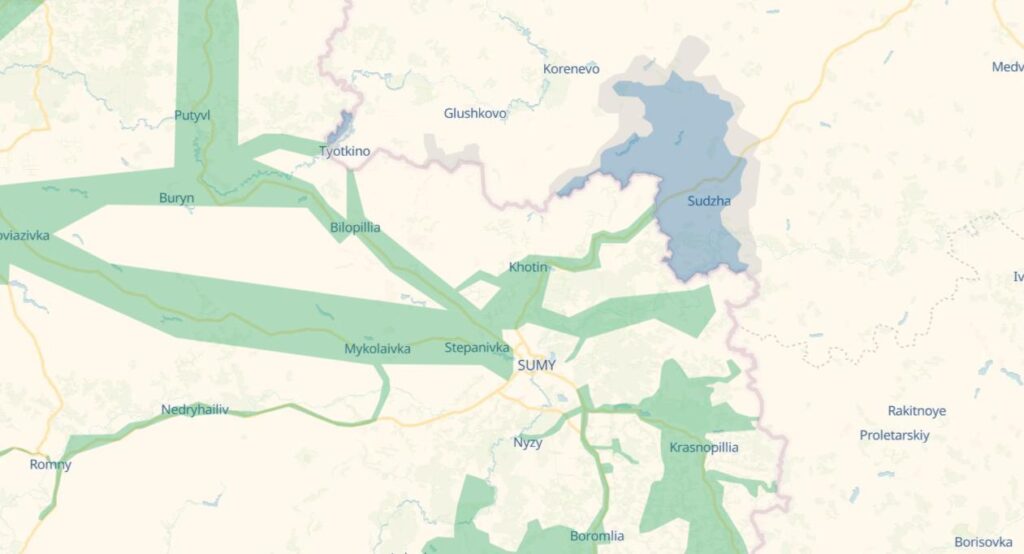

The Kursk Factor

Following Ukraine’s successful incursion into Kursk, Russian political elites are facing a new problem.

If negotiations do take place, Russia won’t be entering from a position of strength: an autocratic regime appears weaker when forced to negotiate over its own territory. Any regime would seek ways to avoid being seen as weak or incompetent internally, so Russia will try to enter talks from a more favorable position.

This suggests Russia may be hesitant to engage seriously in negotiations come November, likely delaying any substantive talks until they attempt to retake Kursk. While Russia is currently struggling to dislodge Ukrainian forces from the area, they are steadily building up troops, preparing for a larger operation in the near future.

While logical, this scenario carries serious risks for the Kremlin: failure to retake Kursk could further damage Putin’s image as a leader who not only failed to defend Russian territory but was also forced to negotiate over it. Despite the state’s propaganda of a powerful Russian army, his inability to reclaim these lands would undermine his internal image.

Failure to retake Kursk could carry serious risks for the Kremlin by undermining Putin’s internal image.

On the other hand, we must consider the possibility that the importance of Kursk and its impact on Russian elites and society may be overstated. They might simply overlook it until the situation becomes an accepted and irrelevant fact, with Kursk becoming a minor factor in Russian decision-making.

This would be especially true if Putin can demonstrate consistent gains in Donbas, pushing further into Ukrainian territory and shifting the focus away from losses elsewhere

Limitations of this analysis

The analysis can’t be considered full or complete without some self-reflection and acknowledging doubts about the data. While the numbers may seem consistent, they don’t necessarily reflect Putin’s rationale, which could operate on entirely different assumptions, like viewing the West as weak or Ukraine’s government as unstable.

The low number of vehicles and economic difficulties might not be enough to compel Putin to end the war. After all, prior to the beginning of the invasion, many individuals and even some professional analysts questioned Russia’s intentions based solely on the number of troops stationed at the border. They concluded that the forces were insufficient to overtake Ukraine and thus believed that Putin would not proceed with an invasion.

He could very well scale down offensive operations, allowing his generals to consolidate gains. By heavily mining the frontlines and continuing missile strikes, he could keep Ukraine in a state of limbo – too dangerous for normal life or business to recover.

With low-intensity combat and reduced military spending, Putin might be able to drag the war out, balancing between war and economics for much longer while waiting for the best possible terms in negotiations.

It is not entirely unrealistic, given that Europe’s trade with Russia’s neighbors, particularly in Central Asia, has been skyrocketing. This trend suggests that Russia may find a path to avoid economic collapse and could continue the war at a lower intensity by leveraging its demographic advantage.

Putin operates under the assumption that Western leaders might lack the resolve to keep helping Ukraine.

Putin is acutely aware of war weariness in the West and operates under the assumption that Western leaders might lack the resolve and incentives to maintain high levels of aid to Ukraine. Foreign assistance is often an unpopular issue in domestic politics, becoming a frequent target for opposition parties that accuse the government of prioritizing foreign spending over pressing issues at home, such as education, healthcare, and infrastructure.

Nevertheless, we can all agree that if the war does not come to an end, its intensity will likely decrease. This means Ukraine needs a long-term plan of action, whether that involves preparing for a potential second invasion or sustaining a low-intensity war.

Editor’s note: A previous version of this article said that only 9% of T-72s remained in storage. It was corrected to say that only 9% were removed from storage.

Related: