Putin’s worst torture camp couldn’t break him. Now he stepped into Assad’s

“I came to see him one day and started explaining my idea, emphasizing how important it was to make a report but that we needed security guarantees.”

It’s not every day that someone walks into the office of Ukraine’s spy chief with an unexpected request. But that’s exactly what Stanislav Aseyev – writer, journalist, and former soldier – said when he faced Kyrylo Budanov, head of Ukraine’s foreign intelligence agency (HUR).

Less than two weeks after Assad’s fall, Aseyev aimed to make history as the first Ukrainian journalist to report from inside Sednaya – Syria’s notorious prison complex, widely regarded as the largest concentration camp since World War II.

“While I was talking, he kept dialing on his phone, and I thought he wasn’t paying close attention,” Aseyev recalled the moment in a video interview with Babel.

“But he was actually calling the person in charge of the evacuation, saying, ‘Now you’ll have a plus one.”

Ukraine’s most daring reporting mission

The next day, Aseyev departed for Syria as part of Ukraine’s first mission to evacuate its citizens from the war-torn country after the regime collapsed. The journey started with a flight to Beirut, followed by a meticulously planned drive to Damascus that required navigating areas where Russian forces and trafficking groups operated.

Russian troops entered Syria in 2015 after Assad sought help against rebel groups, propping up his increasingly unpopular dictatorship. This support lasted until December 2024, when his regime collapsed under the rapid advance of opposition forces led by Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS).

The collapse of Assad’s rule triggered Russia’s gradual and disorganized withdrawal from Homs, where their forces had been stationed at Shayrat airbase — one of the country’s largest. While some units left without their equipment, others retreated to the strategic Beqaa Valley in the country’s north.

Aseyev’s safety was entrusted to the Shaman Battalion (Shamanbat), Ukraine’s elite foreign intelligence unit, which had fought in key battles of the Russian-Ukrainian war, from the 2022 battle of Hostomel to the liberation of Zmiinyi Island later that year.

This time, these veterans were tasked with ensuring Aseyev’s safety — a particularly challenging assignment given his high-profile status and the ongoing surveillance by Russia’s main security agency, the FSB.

Both Ukrainian spies and FSB agents watch his every move for one crucial reason: the man probing Syria’s darkest prison survived Izolyatsia — a notorious torture camp in occupied Donetsk — where he endured tactics mirroring those of Sednaya.

The concentration camp at the heart of Europe

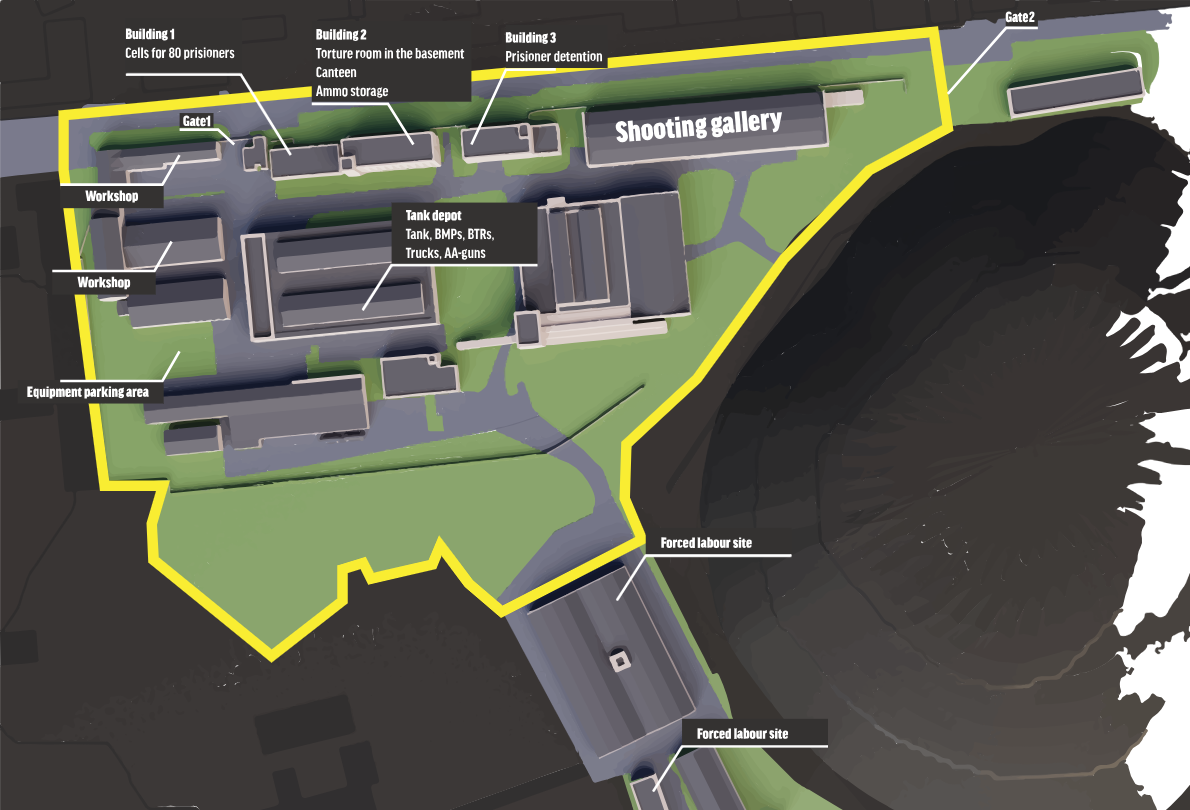

Once a cultural center equipped in a Soviet-time factory, Izolyatsia was seized by Russian-backed forces in June 2014. Its underground bunkers became a secret prison for torturing civilians, journalists, and ex-soldiers accused of opposing the occupation or aiding Ukraine.

At its peak in 2014, the facility held over 100 inmates, with nearly 80 regularly detained in the following years. The exact number of victims remains unknown, as the occupying authorities deny access to human rights organizations.

The underground prison doesn’t formally belong to the official Russian prison system, leaving extreme forms of torture and death of detainees unaccountable. It became one of the first examples of the torture system Russia has established in occupied territories since 2014, expanding into newly occupied areas during the full-scale invasion.

In 2017, Russian-backed forces kidnapped and imprisoned Stanislav Aseyev in Izolyatsia for his freelance reporting on life in occupied Donetsk. In October 2019, after two and a half years of systematic torture, the occupational authorities sentenced him to 15 years on fabricated espionage charges. He was released several months later in a prisoner swap.

“When I tried to share information about Izolyatsia and explain what was happening there, people in the West were very skeptical and said it couldn’t possibly happen in the 21st century,” Aseyev said, explaining the reasons behind his visit to Sednaya.

“Sednaya is just another piece of the larger mosaic, showing that, while we may be in the 21st century, we haven’t moved that far from the mid-20th century,” he said.

Inside Assad’s “human slaughterhouse”

This isn’t just a prison – it’s a death factory, an extermination camp,” Aseyev said of Sednaya, which Amnesty International famously dubbed a “human slaughterhouse.”

Sednaya employed a systematic approach to processing prisoners, including:

- Initial detention in narrow filtration cages;

- Systematic progression through different levels of the facility;

- Mass execution practices;

- Body disposal systems.

Founded in 1987 as a military prison 30 kilometers from Damascus, Sednaya gained notoriety after the outbreak of the Syrian Civil War in 2011. As the government’s war against civil opposition intensified, the number of prisoners soared from 1,500 in 2007 to nearly 20,000 a decade later, according to Amnesty International.

“It feels more like a small, enclosed city, surrounded by a fence with barbed wire, watchtowers, and, according to some reports, even mined along the perimeter,” Aseyev reported from the site to Radio Liberty.

The most striking difference between the two facilities is their scale. While Izolyatsia, at its peak capacity, held approximately 80 prisoners, Aseyev notes that this number “would barely equate to just one cell in Sednaya,” which was designed to hold between 10,000 and 20,000 prisoners.

The facility’s immense size of 1.4 square kilometers (0.54 square miles) makes it the largest concentration camp since World War II, with infrastructure designed for mass detention and the systematic elimination of prisoners. According to Amnesty International, between 5,000 and 13,000 people were executed there between 2011 and 2015.

Of the tens of thousands believed to have been imprisoned there, only about 2,000 were released after Assad’s regime fell on 8 December.

“The question remains: where did all these tens of thousands go? Most likely, the answer lies in the execution and torture chambers,” Aseyev said. “These people were simply exterminated, and perhaps nothing remains, not even their bodies.”

He encountered families still searching the facility for missing relatives, walking the corridors at night, looking for hidden entrances to potential underground cells.

“The very idea that you might be walking over people who are dying right now from the lack of water – that’s what affected me most,” he says.

The anatomy of modern torture camps

Sednaya’s primary purpose of physically exterminating opposition, a function that emerged after Assad’s violent crackdown on dissenters in 2011, marks a key difference from Izolyatsia, where the death of prisoners, although recorded, was not the goal.

This distinction led to differences in the conditions created by the prison administrations in both facilities, despite the extreme brutality and similar torture practices. As Aseyev describes: “At Izolyatsia, you could count the bunks, even in the worst conditions.”

“In Sednaya, it was just tiles on concrete. They’d create a bare space, shove you in, and that was it. You’d sleep however you could — standing, sitting, or sideways,” he said, describing the cells where up to 50 people could be crammed together.

Only long-term prisoners occasionally received makeshift mattresses, while the majority slept directly on the concrete floor, enduring sharp temperature fluctuations both at night and during the day.

However, according to Aseyev, both prisons share the use of systematic torture, though with different methods and scales. While brutal, Izolyatsia operated on a smaller scale, with more individualized torture practices.

He mentioned that the torture system in Izoliatsia followed a graded process, with several stages applied to inmates who couldn’t be broken in earlier ones. The initial stage involved severe beatings, followed by electric shocks — at which point most victims would give in —then sexual violence, and finally, threats to harm the victim’s family.

According to the 2021 report based on survivors’ accounts, the torture system in Izolyatsia included the following practices:

- The deprivation of food, water, sleep, and access to the toilet;

- Beatings, blows with hands and feet;

- Beatings with wooden or metal rods, weapons, or batons;

- Suffocation with plastic bags and water;

- Electric shocks;

- mock executions;

- blindfolding and handcuffing for several days;

- pouring cold water during interrogations;

- forced nudity and other forms of sexual violence;

- verbal abuse and threats, including threats of sexual violence and violence against detainees’ relatives, as well as torture of relatives in the presence of prisoners.

In turn, Sednaya exemplifies large-scale, industrialized detention and elimination, reminiscent of World War II concentration camps.

The prison employed most of the 72 torture methods used by Assad’s regime across 50 facilities for dissenters, as reported by the Syrian Network for Human Rights.

The key features of Sednaya’s torture system include:

- Filtration procedure following initial detention;

- Dedicated torture rooms with specialized equipment;

- Mass rape as a systematic practice;

- Widespread use of electric shock torture;

- System for disposal of remains (including the use of mechanical presses for crushing prisoners and dissolution of remains in acid).

“The very idea that you might be walking over people who are dying right now — that’s what affected me most,” Aseyev told Babel.

The psychology of cruelty

One of the most significant aspects of Aseyev’s analysis is his insight into how ordinary people become capable of extraordinary cruelty. Drawing on the Stanford Prison Experiment, he emphasizes that “cruelty has no nationality.”

Exploring the psychology of cruelty in Izolyatsia, Aseyev cites the example of its notorious commandant, Denys “Palych” Kulykovskyi.

Kulykovskyi, known for his excessive cruelty towards detainees, was detained by Ukraine’s SBU in 2021. The arrest followed a lengthy independent investigation by Aseyev and investigators from Bellingcat, who worked to establish his whereabouts.

“Comparing my stories about Palych from 2017-19, he got progressively worse,” he says. In 2014, he wasn’t like that.”

Drawing on his experience in Izolyatsia, he elaborates that a closed space, inaccessible to eyewitnesses, is the primary and most important condition for the development of a torture mentality:

“I [prison administration] become someone like God – I enter this room, close the door, there are no cameras, the victim is completely restrained with tape or handcuffs. I can do anything without consequences,” he says. “No one will say it’s abnormal because everyone’s around part of it.”

The rising cost of occupation

Stanislav Aseyev points out that the widespread torture and human rights abuses in Russian-controlled territories are another reason why Ukraine cannot abandon its citizens under Russian occupation.

He points out that the aggressive policy of indoctrination systematically carried out in these areas takes a particular toll on the younger generation, who are more vulnerable to Russification through education. As Russian is imposed as the official language, Ukrainian children who started school in the occupied territories in 2014-2015 no longer understand Ukrainian.

Stanislav Aseyev claims that these seemingly insurmountable challenges of reintegration – as well as the reality of rampant human rights abuse, conducted in Izolyatsia and exemplified by Sednaya – explain why Ukraine has no choice but to keep fighting for the liberation of its territories, including his native Donbas region:

“It’s crucial to approach this like Azerbaijan did with Karabakh. Thirty years passed, and they kept saying, ‘This is ours, this is ours, this is ours, we will take it back someday.’”

Read also:

• Putin’s Syrian defeat can crumble under Trump’s Ukraine peace bargain

• What Syria means for Ukraine

• Russia’s African presence at risk from potential Syria naval base loss, expert says