Is Putinism fascism by another name?

The term “fascism” is increasingly used to describe the agenda and actions of the current Russian state under Russian President Vladimir Putin. Today’s use of this label has three dimensions: It is a historical analogy to interpret present events, an expression of Ukraine's lived experience, and a scholarly classification enabling comparisons with other regimes. Understanding these perspectives sheds light on the ideological and practical dynamics behind Putinism and its impact on Ukraine and beyond.

Characterizing Putin’s regime as fascist often serves as a diachronic analogy or metaphorical classification to better understand current developments in Russia and its occupied territories. Drawing parallels with historical events helps to highlight key features and challenges in contemporary Russia. Labeling Putin’s regime as “fascist” aims to clarify for the general public the nature of events unfolding in Russia and in Ukrainian territories under its control.

"Characterizing Putin’s regime as fascist often serves as a diachronic analogy or metaphorical classification to better understand current developments in Russia and its occupied territories."

This comparison is justified by numerous parallels between Putin’s domestic and foreign policies and those of Benito Mussolini’s Italy and Adolf Hitler’s Germany. By late 2024, political, social, ideological, and institutional similarities have accumulated. These range from the increasingly dictatorial and, in some respects, totalitarian characteristics of Putin’s regime to the Kremlin’s revanchist and genocidal tendencies in its external actions. Historian Timothy Snyder has also noted that Russia’s official historical memory and political iconography have, in coded ways, become pro-fascist.

In 2018, Snyder highlighted Ivan Ilyin, a right-wing intellectual from the inter- and post-war Russian emigration who admired Mussolini and Hitler. Under Putin, Ilyin has gained renewed prominence. Snyder describes Ilyin’s work as providing “a metaphysical and moral justification for political totalitarianism” and “practical outlines for a fascist state.” Putin has openly celebrated Ilyin’s ideas, and Ilyin’s influence is evident in the rhetoric of Russian officials, including Dmitry Medvedev, Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov, and Patriarch Kirill of the Russian Orthodox Church.

Putin’s invocation of Ilyin was notably explicit in a speech marking the illegal annexation of Ukraine’s Donetsk, Luhansk, Zaporizhzhia, and Kherson oblasts in September 2022. Putin concluded his remarks with an Ilyin quote: “If I (Iliyn) consider Russia my Motherland, it means that I love, reflect, and think, sing, and speak in Russian; that I believe in the spiritual strength of the Russian people. Its spirit is my spirit; its destiny is my destiny; its suffering is my sorrow; its flowering is my joy.”

For Ukrainians, the term “fascism” functions not only as a historical analogy but also as a verbal expression of collective trauma. Since Russia's invasion in 2014, Ukrainians have coined the term “ruscism” (a blend of "Russia" and "fascism," pronounced “rashyzm”) to describe the Kremlin's genocidal campaign against their nation. This neologism captures the shock and despair caused by Russia's relentless aggression, from airstrikes on civilians to cultural erasure.

The terms “fascism” and “ruscism” are used by the Ukrainian government and society as rallying cries to mobilize domestic and international support against Russian aggression. These labels are meant to highlight the existential stakes of Russia's war of extermination for Ukraine. They signify that Russia's campaign is not merely about territorial conquest. Since 2022, Russia’s revanchist ambitions have focused on annihilating Ukraine as an independent nation-state and distinct cultural community. In this, the Kremlin's words and actions align.

Even before Feb. 24, 2022, statements by Russian officials, lawmakers, and propagandists suggested that Moscow’s goals extended beyond redrawing borders, restoring regional hegemony, or resisting the Westernization of Eastern Europe. Since at least 2014, Russia has ruthlessly targeted Ukrainian national identity, culture, and sentiment.

While it would be an overreach to equate Russian Ukrainophobia with the Nazis' biological and eliminatory antisemitism, Moscow’s irredentist war aims to destroy Ukraine as a sovereign polity and independent civil society. The Kremlin does not seek to physically annihilate all Ukrainians, as the Nazis did with the Jews. However, its agenda goes far beyond harassment, deportation, and indoctrination. It involves the expropriation, terrorization, imprisonment, torture, and murder of Ukrainians (and some Russians) who resist Russia’s military expansion, political repression, and cultural dominance.

"While it would be an overreach to equate Russian Ukrainophobia with the Nazis' biological and eliminatory antisemitism, Moscow’s irredentist war aims to destroy Ukraine as a sovereign polity and independent civil society."

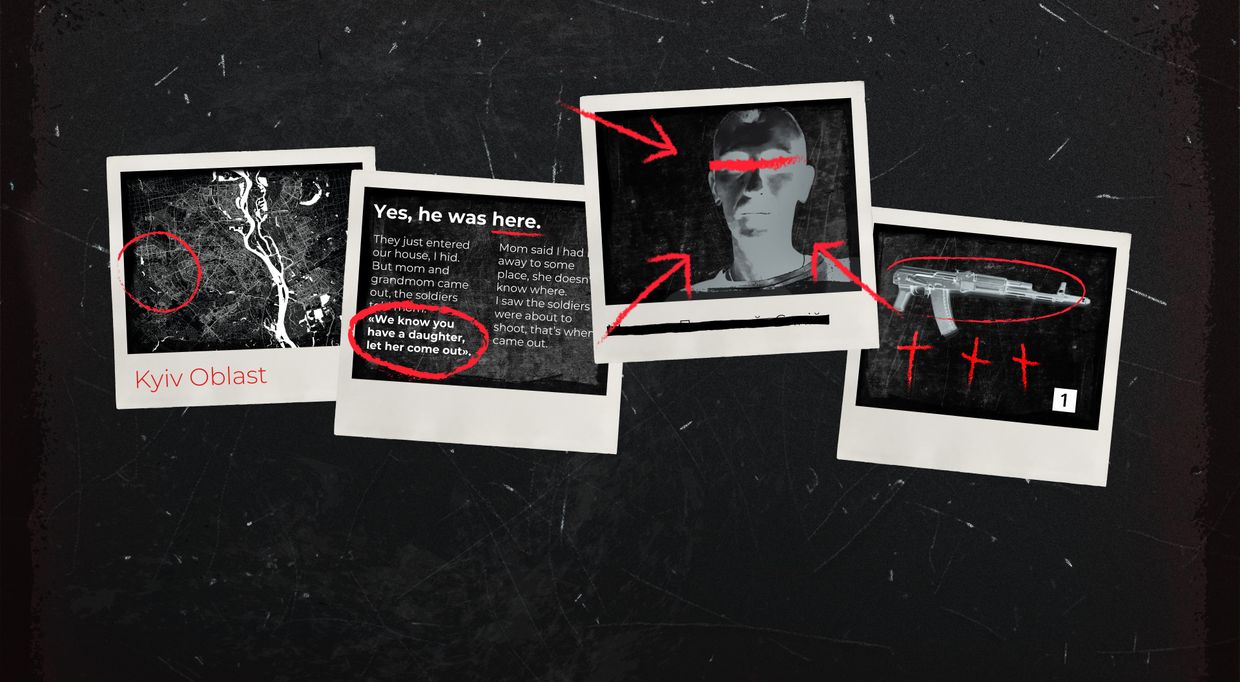

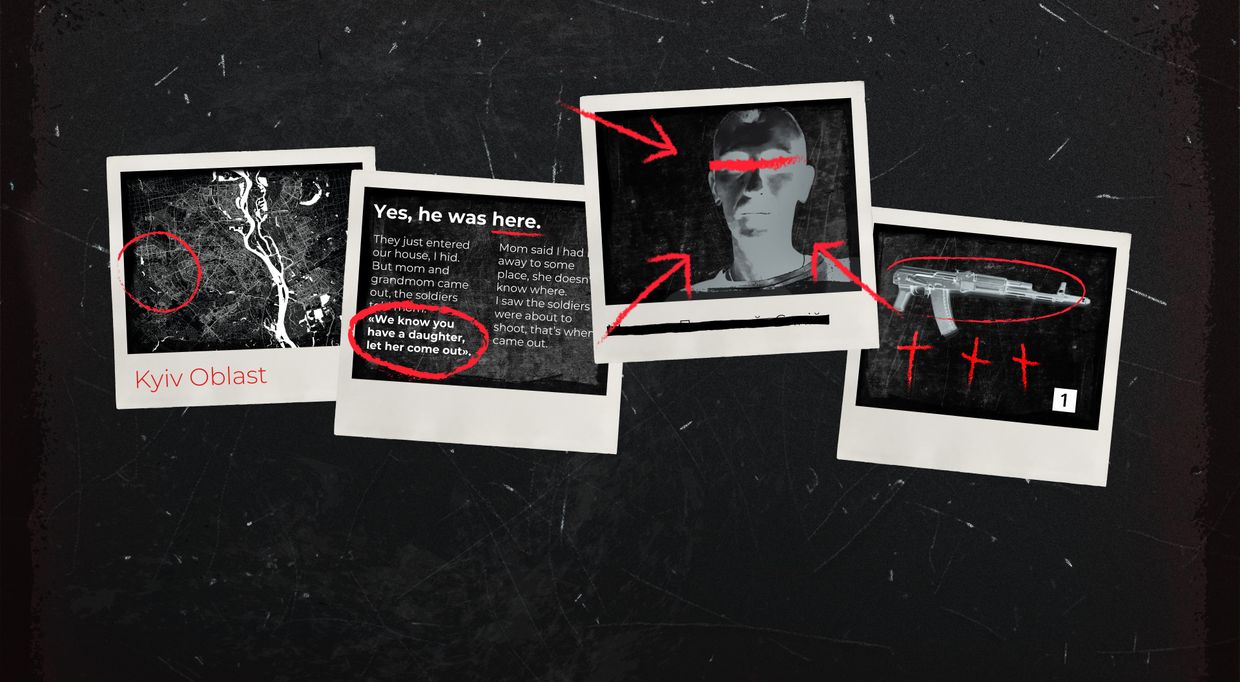

Given this context, it is unsurprising that many Ukrainians and some Russian observers describe Russia's actions as “fascist.” For millions of Ukrainians living under occupation or returning to a war-torn homeland, Moscow’s brutality is made manifest through relentless airstrikes, which frequently target civilian infrastructure — homes, supermarkets, hospitals, and schools — rather than military sites.

Military historians might argue that targeting civilians is not unique to fascist warfare. However, for most Ukrainians, the term “fascism” captures their reality and resonates with their collective memory of historical fascism, particularly German Nazism. For older Ukrainians who lived through World War II and younger who learned about it from their parents or grandparents, the parallels with the Luftwaffe's air raids on civilian populations, Third Reich’s occupation policies, and Nazis’ anti-Slavic racism are stark.

An increasing number of experts on Central and Eastern Europe now describe Putin's Russia as fascist. However, many comparative historians and political scientists hesitate to use this term due to their narrow definitions of generic fascism. For these scholars, a defining characteristic of fascism is the pursuit of political, social, cultural, and anthropological re- or new birth, rather than restoring a past order.

Fascists often mythologize a Golden Age from their nation’s distant past but aim to forge a new national community rather than to preserve or revive the currently decaying order. Unlike the revolutionary nature of fascism, Putinism seeks to restore the Tsarist and Soviet empires instead of creating an entirely new Russian state, culture, and identity. For this reason, many comparativists refrain from categorizing Putin’s regime as fascist.

Nevertheless, Putinism has evolved significantly over the past 25 years. Putin began his political career under pro-Western democrats Anatoly Sobchak and Boris Yeltsin. Early in his presidency, Russia maintained liberal and pro-European elements, and remained a member of the Council of Europe, NATO-Russia Council, and G8. Moscow even negotiated a deepened partnership agreement with the EU until 2014.

However, Putin’s rise to power in 1999 marked the start of Russia’s regression from a proto-democracy to an autocracy. In 2007, during his infamous Munich Security Conference speech, Putin signaled a decisive turn away from the West. Over time, his regime became increasingly illiberal, nationalist, imperialist, and militaristic, with a partial pause during Dmitry Medvedev’s palliative presidency. By 2022, Russia’s pseudo-federation had shifted from semi-authoritarian to semi-totalitarian, culminating in the full-scale invasion of Ukraine and alignment with authoritarian Asian states.

The regime’s regression has been marked not only by escalating rhetorical aggression, internal repression, external escalation, and political radicalization. Putin and his entourage now routinely threaten to employ nuclear weapons. Russia also implements a kind of agenda in the occupied Ukrainian territories that resembles fascist strategies.

In the occupied territories, Russia’s russification campaign employs terror, forced reeducation, and material incentives to impose a profound sociocultural transformation. While such revisionist policies are not inherently fascist, the Kremlin’s methods and goals — turning Ukrainian communities into ideologically standardized cells of a unified "Russian people" — share similarities with the attempted fascist revolutions of Mussolini’s Italy and Hitler’s Germany.

Russian imperial ultranationalists view Ukraine as part of “New Russia” or “Little Russia,” dismissing Ukrainians as a merely sub-ethnic group of the greater Russian people. In their narrative, Ukrainians have been misled by foreign actors — be it the Catholic Church, Imperial Germany, the Bolsheviks, or the West — into forming an artificial nation. This irredentist vision portrays Ukrainians as border-dwellers of the Russian empire rather than citizens of an independent state.

Moscow’s occupation policy seeks to reverse this perceived “civilizational split” by conducting a rebirth of "Little Russia" within the annexed territories. This involves a political, social, cultural, and anthropological transformation reminiscent of fascist domestic and occupation policies. While population homogenization campaigns are not exclusive to fascism, the Kremlin’s russification efforts in Ukraine align closely enough with classical fascist strategies to be considered quasi-fascist.

Russia’s current internal situation is still far from full-fledged fascism, as Putin and his circle are no domestic revolutionaries but representatives of the pre-1991 “ancien régime.” Rather than forging a novel empire, they aim to restore the Tsarist and Soviet orders as much as possible. In this sense, Putin is less akin to Hitler and more comparable to Germany’s last Reich president, Paul von Hindenburg, who enabled Hitler’s rise to power by appointing him Reich chancellor on Jan. 30, 1933.

Within Russian pan-nationalism, Ukraine is viewed not as a foreign country but as the western frontier of Greater Russia. While most outsiders interpret Moscow’s aggressive Ukraine policy as an implementation of Russia’s foreign political priorities, many Russians see it as an internal affair. This perception frames the treatment of Ukraine as a family matter, where the norms of international law and humanitarian conventions are deemed irrelevant.

For Ukrainian victims and international critics of Russia’s actions, the refusal of many scholars to label Putin’s regime as fascist can seem inadequate, disingenuous, or even amoral. Russia’s forces and occupation authorities in Ukraine — particularly since the full-scale invasion of 2022 — have engaged in horrendous acts of terrorism, genocide, and sadism. Insisting that these actions are unequivocally and exclusively non-fascist feels jarring in light of atrocities like the mass murders in Bucha and Mariupol, destruction of the Kakhovka Dam, mass deportation of Ukrainian children, routinized torture of the vast majority of Ukrainian prisoners of war, and targeted airstrikes on apartment buildings, universities, and libraries all over Ukraine.

"For Ukrainian victims and international critics of Russia’s actions, the refusal of many scholars to label Putin’s regime as fascist can seem inadequate, disingenuous, or even amoral."

These crimes are neither incidental byproducts of military operations nor singular aberrations by local commanders nor standard neocolonial practices. A cautious classification of the ideology behind Russia’s war of extermination as merely “illiberal,” “conservative,” or “traditionalist” seems thus grossly insufficient. Many who have studied the harrowing details of Russia’s mass terror campaign in Ukraine would find such descriptors misleading.

At the same time, reducing Putinism solely to fascism oversimplifies its nature. Explaining Moscow’s aggression purely as an outgrowth of ultra-nationalist fanaticism ignores the political pragmatism behind many of its actions. While fascists exist within Russia’s political and intellectual elite, most of the country’s key policymakers are cynics rather than fanatics.

A significant factor in Russia’s pre-2022 foreign policy adventures was their perceived ease and reward. Earlier military interventions in Georgia, Ukraine, and Syria were not only tactically successful but also bolstered Putin’s domestic standing. These campaigns stabilized Putin's rule in Russia’s largely conformist society, where victories abroad translated into popular support at home.

By early 2022, as Putin’s approval ratings were waning again, a repetition of the pattern of previous foreign interventions may have seemed rational given their prior victories on the ground and enthusiastic perception at home. Russia’s earlier military ventures had proven politically advantageous, strategically predictable, militarily effective, economically manageable, and widely popular. From this perspective, the decision to escalate in Ukraine reflects not just a murderous ideology but also calculated pragmatism.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed in the op-ed section are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Kyiv Independent.