Inside Ukraine’s kitchen drone labs halting Russia’s war advance

The Russian-Ukrainian war has redefined modern combat, with drones firmly at the forefront as the most game-changing innovation.

Since the war’s early days a decade ago, drones have become a silver bullet of Ukrainian ingenuity, taking on Russia’s far superior military. Once cheap reconnaissance tools, they’ve transformed into indispensable weapons, driving intelligence, logistics, ground operations, and naval attacks.

The role of drones has surged so dramatically that in June 2024, Ukraine established the Unmanned Systems Forces (USF), becoming the world’s first country to create a dedicated branch of its military for drone warfare. This innovation was paired with the government’s ambitious goal to produce one million drones in 2024 — a target set at the end of 2023 and surpassed by October 2024.

This leap was powered by more than 200 state-owned and private drone manufacturers, ranging from small startups to large-scale producers. Yet, just as drones sparked a revolution in Ukrainian warfare a decade ago, their production has done the same for the nation’s weapons industry.

Many of the drone makers driving the nation’s technological leap are ordinary civilians, equipped with nothing more than free online courses, 3D printers, and post offices that deliver their creations straight to the front.

Ukraine’s kitchen-table defense industry

While defense manufacturing usually conjures images of sprawling factories with assembly lines cranking out weapons, Ukraine is rewriting the playbook. In addition to traditional factories — some tucked underground to shield them from Russian strikes — it’s embracing a decentralized model that proves more agile.

Now, decentralized production networks unite thousands of Ukrainians working on drone manufacturing projects from their homes, coordinating production and logistics online, and shipping finished products straight to military units.

While the scale of this networked production is still small, with even the fastest workers assembling just a few drones a day, it offers drone enthusiasts a stepping stone to larger projects — or even the chance to start their own drone factory.

27-year-old software engineer Mykhailo Karpyshyn is one of many Ukrainians who answered the call to join weapons production efforts. In just a few months, he went from volunteer assembler to military drone operator, now piloting sophisticated drone bombers. However, it all started in a small flat-turned-workshop.

Now, this small apartment is lined with 9-inch FPV drone frames stuck to the walls, waiting to be turned into fully functional drones, though they serve as décor for now. Two 3D printers hum away on the table, churning out plastic parts for drones and munitions.

Mykhailo’s computer is plugged into a backup power battery, so in case of a Russian missile strike, it can run for a few extra hours during a blackout until the power is restored.

Karpyshyn has already built and delivered over 20 drones to Ukrainian troops, using his own funds to purchase parts — far cheaper than buying ready-made drones. To cut costs even further, he prints hundreds of components on his 3D printers, setting them up for the task each morning.

Karpyshyn is just one cog in a vast, volunteer-powered network fueling Ukraine’s military effort. He’s part of the Druk Army (Printing Army), a growing online force of hundreds of Ukrainians with 3D printers, printing the future of the fight.

An army behind the Army

“A 3D printer costs just $250, anyone can set it up at home with no harmful fumes, and you can start printing in just a few days,” reads the official Druk Army page.

Mykhailo was one of many volunteers who turned this idea into action, transforming their printers – now nearly 10,000 in total – into a powerhouse of innovation for Ukraine’s defense. Today, the network produces more than 500 items, varying from medical tools to grenade-dropping components.

By October 2024, the initiative had delivered over 275 tons of various plastic parts to the frontlines and set up warehouses stocked to keep deliveries flowing in case Russian airstrikes cause blackouts that hinder production.

After a quick registration and basic training, new volunteers can download 3D models provided by Druk Army coordinators. These models are shared on a dedicated online platform that lists the required quantities for each part.

Volunteers select the parts they can produce based on their printer capacity, while the platform tracks progress automatically, flagging when a task is completed.

Once the parts are printed, volunteers ship them to coordinators for testing via Nova Poshta, Ukraine’s largest postal service. With lightning-fast delivery times of just 12–36 hours, even to frontline areas, the service ensures swift logistics to the next stage.

After testing, the parts are sent to production facilities or delivered directly to frontline towns and villages, ready for action.

The range of plastic parts used in drone warfare is vast, from projectile wings and tail sections to shell attachments and beyond.

People’s FPV: Ukraine’s backyard drone-making rear

However, the ability to create drones for the army isn’t limited to tech-savvy volunteers with 3D printers — it’s open to all civilians.

Small aerial drones, such as FPV (first-person view) drones, can be built by any citizen after minimal training. In 2024, Ukrainian drone activist Maria Berlinska, who championed the idea of a drone army in war’s early days ten years ago, teamed up with the Dignitas Fund to launch the Narodnyi FPV (People’s FPV) project, part of the broader Victory Drones initiative.

Thanks to this initiative, any Ukrainian can now learn to build a drone from scratch with a free course on Prometheus, Ukraine’s largest online education platform.

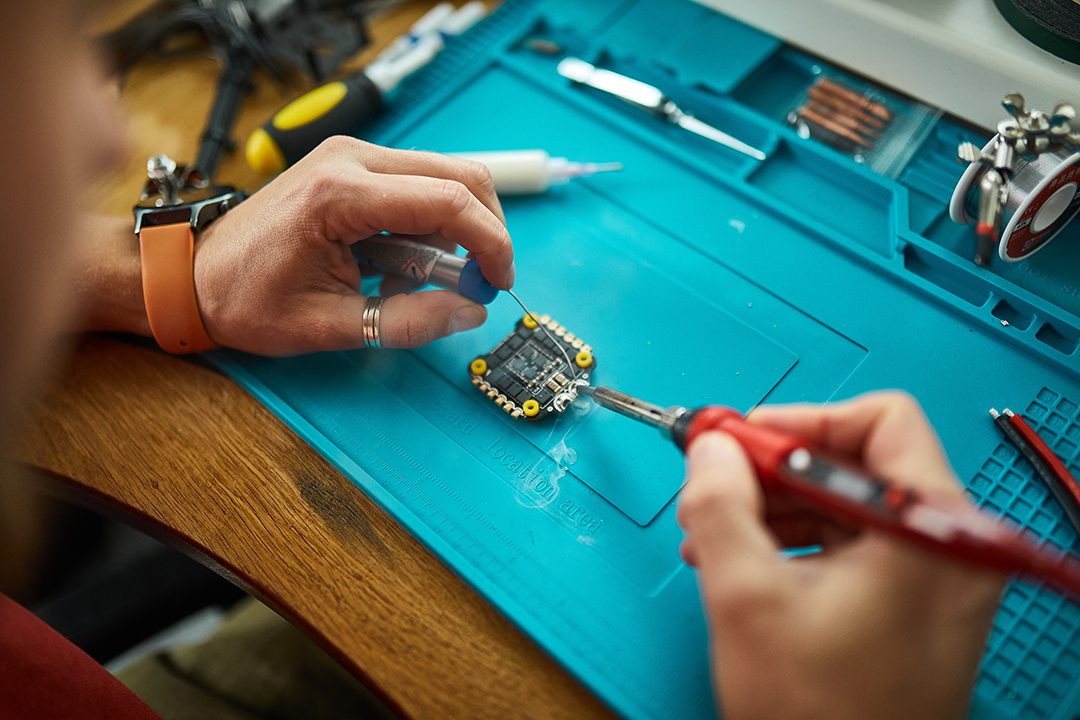

Beyond teaching assembly, the course covers the key drone parts — frame, motors, propellers, flight controller, and camera. While beginners can stick to standard models, advanced builders can craft custom drones or even launch their own serial production — and a social mission woven into the fabric of the course.

All a novice needs is a basic soldering station, drone parts, and a few affordable tools like a screwdriver and electronic cleaner. From a technical standpoint, assembling the drone is much like building a toy model, with the added step of soldering cables between the parts.

Once assembled, volunteers configure the drone using ready-made software, then send it to specialists for testing. After passing the tests, the drones are dispatched to the frontline, ready for action.

As of now, thousands of volunteers have completed the Victory Drones training, producing over 3,000 drones through the program. Many have gone on to join the military or production facilities, making the impact far greater than just numbers.

For Maria Berlinska, the course is at the heart of her vision for the “technological militarization of society” — the only path she sees for Ukraine to defeat a stronger enemy like Russia.

People’s FPV isn’t the only initiative guiding civilians to build drones for the military. A variety of guides and resources are available to help people assemble drones for the units they support. Meanwhile, several centralized projects resembling People’s FPV collect, test, and deliver drones directly to the frontline.

The razor-edge war technology race

Initially championed by grassroots initiatives, small, inexpensive drones were quickly recognized by Ukrainian civilians for their potential in warfare. As the full-scale war progressed, the Ukrainian government began taking these new weapons seriously, launching the Army of Drones project.

In 2023, the state provided over 300,000 drones to the Ukrainian army through this initiative, according to Ukraine’s Ministry of Digital Transformation.

Around 90% of the drones supplied to Ukraine’s military are homegrown, with over 200 Ukrainian companies leading the charge. These companies are focused on localizing production, making as many parts as possible within Ukraine itself.

Adapting to the evolving tactics of drone warfare, the Ukrainian military has become the first in the world to establish dedicated strike drone companies within each brigade and other large units — totaling 67 such companies by the start of 2024.

Meanwhile, Russia has rapidly adapted to drone warfare, scaling up its domestic drone production. The Kremlin’s track has shifted from the reliance on importing allies’ technology, mainly Iranian-made Shahid – to ramping up centralized domestic production.

Russia’s drone production still trails Ukraine’s — by October 2024, Putin had only announced plans for 1.4 million drones, a target Ukraine had already hit — but that gap could close fast. In 2023, Russia poured $3 billion — half of Ukraine’s total 2024 arms procurement budget — into boosting production, raising alarms among Ukrainian pioneers like Maria Berlinska.

Berlinska, one of Ukraine’s leading drone experts, has long warned that Ukraine needs at least 3.5 million drones annually to stay competitive. But the real threat isn’t just the numbers — Russia’s growing edge in quality could soon tip the scales in its favor.

She warns that Russian engineers are on the brink of a game-changer. With thermal cameras and computer vision, their drones can already lock onto targets with minimal human input. Leveraging this tech, Berlinska cautions that Russia is dangerously close to unleashing drone swarms that will operate autonomously, guided entirely by algorithms.

Ukrainian drone operator and instructor Serhiy Ristenko echoes her concerns, stressing that both quantity and innovation are crucial in this high-tech battle. He explains that there’s a constant race between electronic warfare (EW) systems and drones. As soon as EW systems can counter a new type of drone, the drones must be revamped to stay one step ahead.

In the drone race, he warns, speed is the name of the game.

Read also:

• Ukraine deploys demining drones to break Russia’s Dnipro wall

• An entrepreneur’s journey to leading one of Ukraine’s deadliest drone units

• Chasiv Yar’s survival rests on daring night drone team

• Russian drones terrorize Kherson civilians with “human safari”