Global instability 2025: Analysis shows growing economic, political and climate risks

If you think the world is sliding into chaos and unpredictability — you’re not wrong. While countless analyses have tackled this global turbulence, few delve into its fundamental causes: the deep demographic, social, and economic processes, climate change, and scientific-technical shifts that shape our reality. Let me paint you a picture of how we got here.

1. The origins: how stability bred instability

Ironically, the path to today’s instability began at the moment of greatest stability — the end of the Cold War. In 1990, as the Soviet Union ceased to be the West’s opponent (even before its formal collapse), the world entered a brief period of unprecedented certainty. Economic, political, military, and cultural power concentrated in one center: broadly in the democratic “Western world” and specifically in the United States.

This new global order operated on clear rules: comply or face consequences.

Sometimes these consequences exceeded reasonable bounds, as witnessed in Iraq in 2003. This era of certainty and concentrated power enabled a wave of globalization — both economic and socio-political — that dominated from 1990 until the 2008 global financial crisis.

Economic globalization created multiple winners: transnational corporations rushed to move production to Asia, resource-rich countries like Russia profited from rising commodity prices, and China and its populous neighbors achieved dramatic economic growth by offering cheap labor to Western capital.

On paper, almost everyone got richer — West, East, and South alike. But beneath the surface, societies were transforming in vastly different ways.

Take Russia: A flood of petrodollars coincided with Putin’s rise to power, enabling him to systematically dismantle the nascent democratic institutions of the early 2000s. He skillfully leveraged Russia’s market reforms of the 1990s (which, ironically, he criticized but never reversed) and oil wealth to build a power vertical, establish information control, and pacify the population with relative prosperity.

The result? An amorphous, depoliticized society under authoritarian control.

China’s trajectory during this period followed a different but equally significant path. The Chinese Communist Party cemented its legitimacy by finally delivering basic prosperity to its population — something not seen since before the Opium Wars. As hundreds of millions of Chinese citizens moved from abject poverty to modest stability, the party consolidated power and began projecting international influence.

Both Russia and China, along with Brazil (though democratic) and roughly twenty other nations, eventually hit what economists call the “middle-income trap” — a development ceiling where easy economic gains are exhausted and further progress demands fundamental institutional reforms. Among authoritarian states, only Singapore successfully navigated this transition; others either democratized or stagnated (with small, oil-rich Gulf states being the rare exceptions).

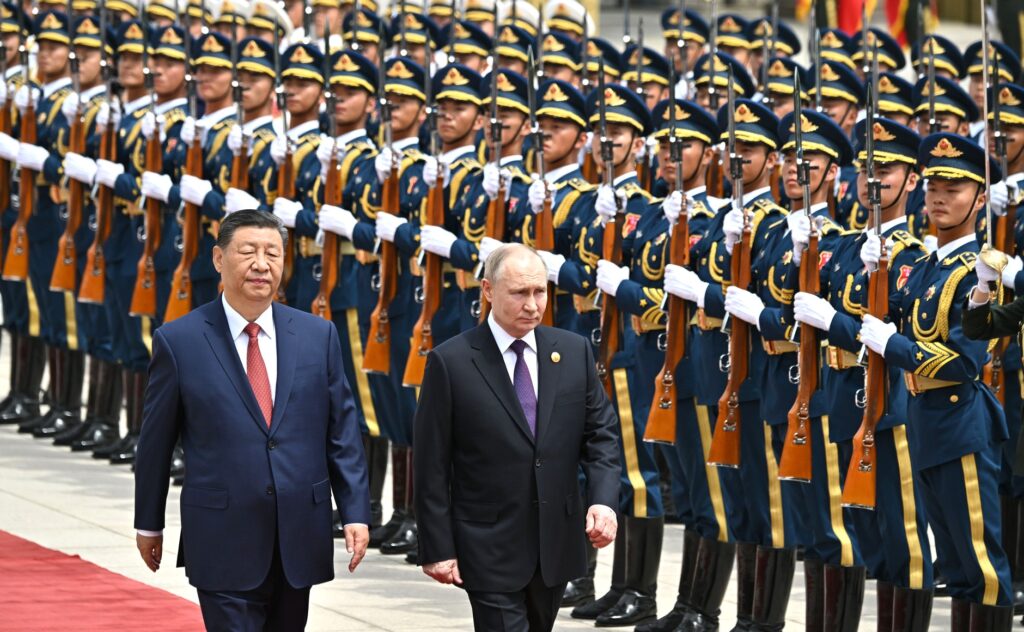

For Russia and China, the logical path forward should have been democratization, supported by their growing middle classes. Instead, their ruling elites chose a different route: preserving autocracy by manufacturing external threats.

Meanwhile, the West experienced its own transformations. While corporations prospered, the bedrock of Western stability — the middle class — began crumbling.

The “Great Transfer” of manufacturing to China triggered a dual crisis: the physical loss of industrial jobs and the devaluation of industrial labor across Europe and North America. In the United States, this deterioration accelerated with the implementation of an unbalanced free trade agreement with Mexico in the early 1990s — a move that benefited corporations while further undermining workers and the broader middle class.

Globalization’s effects reached beyond social classes to reshape geography itself. Major cities evolved into concentrated centers of economic power, while peripheral regions lost access to resources and opportunities. This urban-rural divide added another layer to growing societal tensions.

The increasing power of global corporations and financial markets over national economies created particular challenges for democracies and smaller nations. Many governments, especially those with limited economic leverage, found themselves unable to resist global market forces — a dynamic that undermined state sovereignty and fueled populist demands for its restoration.

Then came the migration challenge. This population movement strained social cohesion and accelerated the erosion of traditional political consensuses.

These compounding pressures intensified social divisions, creating entire segments of “forgotten” populations — former industrial workers, struggling middle-class families, and marginalized migrants.

The weakening of the middle class particularly undermined moderate political voices, especially social democrats, leading to growing distrust in democratic institutions perceived as ineffective or compromised. This erosion of faith in traditional politics created fertile ground for both left and right-wing populism, making it increasingly difficult for democracies to implement merit-based policies instead of populist compromises.

Ironically, autocratic regimes proved adept at exploiting globalization’s opportunities while maintaining tight domestic control. Russia and China masterfully used open global markets to export resources and expand influence while carefully restricting foreign access to their internal markets and protecting domestic power structures. Their success as alternative development models has only grown over recent decades, even though their societies remain deliberately underdeveloped to maintain control.

Russia and China exploited globalization’s opportunities while maintaining tight domestic control over the population, which remains deliberately underdeveloped.

2. Dimensions of current instability

Today’s world grows increasingly unpredictable, and this broken equilibrium won’t right itself anytime soon — perhaps not for a decade. The interplay of economic crises, geopolitical conflicts, climate change, and technological disruption creates a complex web of destabilizing factors. Let’s examine the key drivers of this instability:

- Global economic inequality: The widening wealth gap between and within nations creates dangerous social tensions. With over 700 million people still living in poverty while the richest 1% own more than the rest of humanity combined, we’re seeing inequality fuel political radicalization and economic instability worldwide.

- Global inflation and energy crisis: The triple impact of COVID-19, the Ukraine war, and supply chain disruptions continues to erode purchasing power globally. The challenging transition to green energy, complicated by geopolitical tensions, further strains economic stability.

- Resource scarcity in the tech transition: The growing demand for rare earth metals, coupled with climate-driven food and water insecurity, intensifies international competition. China’s dominance in rare metals markets and Russia’s attempted weaponization of energy resources demonstrate how resource control increasingly shapes global power dynamics.

- Climate change: Regardless of ongoing debates about causes, the consequences affect everyone. More frequent extreme weather events strain infrastructure, disrupt agriculture and increase epidemic risks. The Global South faces particular vulnerability, with projections suggesting 200 million climate refugees by 2050.

- Information revolution: The digital transformation of global communication has accelerated disinformation’s spread, fundamentally challenging democratic processes. Social media platforms have become powerful vectors for both unintentional misinformation and deliberate manipulation by authoritarian regimes, populist politicians, and malicious actors. Traditional institutions — from education systems to mainstream media — struggle to adapt quickly enough to counter these forces.

- Technological revolutions: We’re witnessing multiple transformative shifts simultaneously: automation’s “new industrial revolution,” the search for sustainable energy sources, and artificial intelligence’s rapid emergence. Each advance brings both opportunities and risks. Cybersecurity threats exemplify these dual implications — attacks on critical infrastructure, financial systems, and government institutions have surged 70% in three years, according to European cybersecurity authorities.

- Paralysis of global institutions: Organizations designed to manage international conflicts and challenges, particularly the UN, have become increasingly ineffective. This institutional failure stems from multiple sources: excessive bureaucracy, major powers’ abuse of veto powers (particularly by the US, China, and Russia), and chronic underfunding. The result is a more chaotic, less manageable world order.

- Leadership vacuum: Traditional global powers either abdicate responsibility or actively contribute to instability. The US-China economic and technological rivalry intensifies while Russia positions itself as a destabilizing force, waging Europe’s largest conflict since World War II. Meanwhile, emerging powers like India, Iran, Türkiye, Saudi Arabia, Japan, Indonesia, and the European Union pursue their regional interests, further complicating global dynamics.

3. The 2025 outlook and beyond

2025 promises unprecedented turbulence. Recent years have already brought Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, renewed Middle Eastern conflicts, and Sudan’s devastating civil war. Political upheavals in Bangladesh and Syria, alongside numerous African coups, suggest this pattern of instability will continue.

Economically, forecasts indicate sluggish global growth accompanied by persistent inflation in food, energy, and raw materials markets. Resource scarcity will particularly impact import-dependent European economies. The rapid advancement of AI and automation will reshape labor markets and political landscapes, while US-China technological competition risks splitting the world into competing digital spheres.

The potential US-China trade war (possibly expanding to include the EU and Canada) threatens to further slow global economic growth. These economic pressures will likely intensify military and political instability.

China’s economic slowdown and mounting debt crisis could push Xi’s regime toward more aggressive external policies, including potential action against Taiwan. Meanwhile, tensions simmer between India and Pakistan, across Central Asia, and in the South China Sea.

We must also face two inexorable forces: climate change and migration. Whether we accept or deny them, these phenomena cannot be stopped without addressing their root causes.

Migration pressures will intensify as instability spreads — while Syrian refugees may gradually return home, the Sudanese crisis promises to create even larger displacement. Europe and the Middle East have yet to feel its full impact, and the prospect of new conflicts erupting in Africa or Asia could dwarf current challenges.

These compounding crises will likely strengthen demands for authoritarian solutions in democratic societies while simultaneously undermining autocracies’ long-term legitimacy.

For the average person, this means living with constant uncertainty: here a dictatorship falls, there a default occurs, elsewhere drought triggers famine and mass migration, while ultra-right populists gain power in previously stable democracies.

Russia under Putin faces particular challenges in this unstable environment. Having depleted significant resources in its war against Ukraine, Russia has become more vulnerable to systemic crises, terrorist attacks, or shifts in global resource demand. Unlike during the crises of 1991 and 1998, today’s Russian society suffers from intense internal divisions and demographic decline. Putin must now balance between managing chaos and risking its uncontrolled spread within his own system.

For Ukraine, this situation presents both challenges and opportunities. Understanding global demands — particularly for food security — must shape our priorities. Ukraine needs to:

- Maintain a consistent, pragmatic foreign policy;

- Strengthen ties with nations facing similar threats;

- Expand export markets in Africa, Latin America, and Southeast Asia;

- Transform its diplomatic presence from symbolic to substantial;

- Develop its defense industry, particularly in drones and modern military equipment;

- Participate in green initiatives to modernize its energy sector and industry.

The path forward requires remembering a fundamental principle: systemic problems cannot be solved at the same level of management that created them. While globalization initially promised stability and development, it became a catalyst for new challenges — deepening inequality, empowering autocracies, and weakening democratic institutions.

The solution demands building a new model of global governance that genuinely considers all countries’ and social groups’ interests. However, this transformation will likely only come after a systemic crisis — hopefully without global war — and possibly a new, multipolar “cold war” between major global powers.

Autocracies cannot sustain such a new world order due to their inherent contradictions. Yet democracies, too, must evolve, developing new mechanisms for effective coordination to restore global stability. This requires:

- Rethinking approaches to inequality (traditional social policies and tax regulations have proven insufficient);

- Returning to foundational solutions like universal access to education;

- Creating robust frameworks for managing digital platforms and AI to prevent manipulation;

- Reforming international institutions, particularly the UN;

- Establishing new platforms for technology regulation and climate action;

- Building resilient infrastructure for extreme weather;

- Developing renewable energy sources;

- Creating strategic resource reserves to reduce dependence on autocratic powers.

We likely cannot reverse climate change entirely or eliminate all autocracies simultaneously. However, we can adapt to these challenges while working toward long-term solutions. This path is difficult but necessary — it’s our only route to a more stable, equitable world.

The current global turbulence may be our new normal, but it also presents an opportunity to rebuild our international systems more thoughtfully. Success requires understanding that quick fixes won’t suffice — we need fundamental reforms addressing root causes rather than symptoms. Only by acknowledging this complexity and committing to long-term solutions can we hope to create a more resilient global order.

The choices we make in navigating these challenges will determine whether this period of instability leads to a more just and stable world or deeper chaos. The stakes couldn’t be higher, and the responsibility falls on both democratic institutions and civil society to guide this transition thoughtfully and deliberately.

Related: