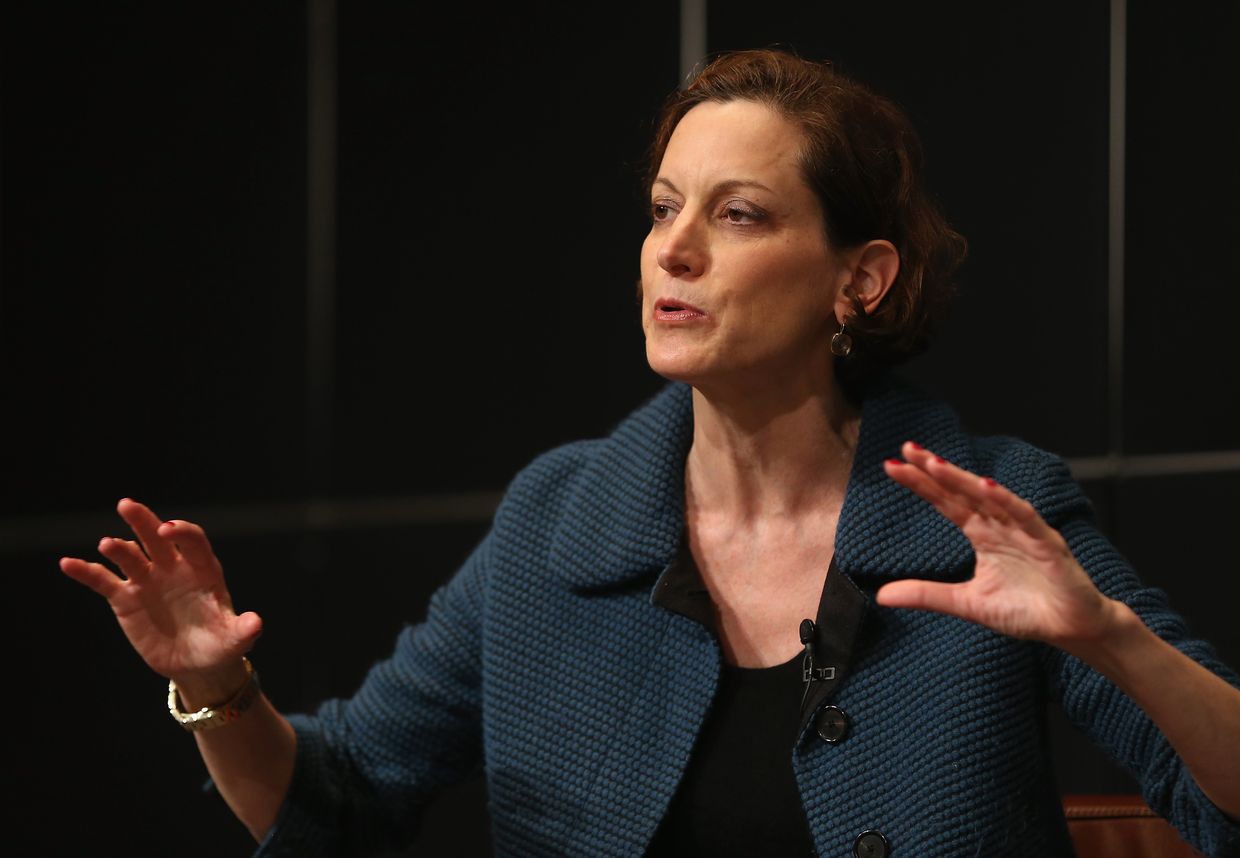

Deals over ideals — Anne Applebaum explains the playbook of autocracies in new book, and how to undermine them

Autocratic regimes like Russia are becoming increasingly bold in their efforts to undermine the principles and norms that came to define the democratic world order in the aftermath of World War II. A month after the start of the full-scale war against Ukraine, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov even declared “this is not about Ukraine at all, but the world order.”

“The current (war) is a fateful, epoch-making moment in modern history,” he continued. “It reflects the battle over what the world order will look like.”

As Ukraine's Western allies grapple with how far they can go in supporting the embattled country against a war of total annihilation, Russia's intent reveals not only a profound contempt for the Ukrainian people, their history, and culture but also a broader aspiration to reshape the world into a landscape marked by the erosion of individual freedoms and consolidation of power at the top.

In her latest book, “Autocracy, Inc.,” U.S. journalist and historian Anne Applebaum delves into the intricate web of financial, technological, and police networks that autocracies such as Russia, China, North Korea, and Iran have cultivated to bolster one another. She examines how these regimes, in some instances, have begun to operate as if with complete impunity, disregarding international condemnation and withstanding the impact of severe economic sanctions.

The autocratic leaders of today, Applebaum argues, are not driven by spreading ideologies of the past such as communism or fascism. They “share a determination to deprive their citizens of any real influence or public voice, to push back against all forms of transparency or accountability, and to repress anyone, at home or abroad, who challenges them.”

The alliances between these countries are forged through "deals, not ideals," enabling them to sidestep the burden of Western financial sanctions that many face. The arrangements between these countries frequently involve the exchange of surveillance technology to bolster internal control over their populations or the mutual enrichment of the considerable wealth they have accumulated.

Belarus is one of the more striking examples cited by Applebaum. Despite widespread unpopularity among the Belarusian population and condemnation from international bodies like the European Union and the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, Belarusian dictator Alexander Lukashenko has managed to remain in power for the past three decades. The relatively small country is not as isolated as it may seem, nor is it facing a major economic crisis.

Belarusian goods are barred from the EU market due to sanctions, and its national airline, Belavia, is prohibited from flying to European destinations. However, as Applebaum notes, Belarus has found alternative economic partners. “More than two dozen” Chinese companies have invested in its economy, while Russia has long provided the country with a crucial financial lifeline.

The relationship between Belarus and Russia is deeply interdependent. When some Belarusian journalists refused to cover up Lukashenko’s widespread election fraud during the 2020 presidential election, for example, Russian state-affiliated media sent their own journalists to take their place. Since the onset of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Belarus has effectively served as both a military base for Russian troops and a launchpad for attacks on Ukrainian territory.

As autocratic regimes seek out like-minded allies to forge an alternative to the democratic world order, we are witnessing a number of troubling trends, such as the targeting of dissidents abroad. This alarming strategy sends a clear message — that these regimes believe they are on the advance and nothing can stop them.

According to Applebaum, “the conviction, common among the most committed autocrats, that the outside world cannot touch them – that the views of other nations don’t matter and that no court of public opinion will ever judge them – is (a) relatively recent (phenomenon).”

“The conviction, common among the most committed autocrats, that the outside world cannot touch them – that the views of other nations don’t matter and that no court of public opinion will ever judge them – is (a) relatively recent (phenomenon).”

One disturbing example is the kidnapping of Belarusian opposition journalist Roman Protasevich from a Ryanair flight from Athens to Vilnius in 2021. When the plane crossed through Belarusian airspace, Belarusian air traffic falsely told the pilots of the Irish-owned airline that a bomb was on board. MiG fighter jets were dispatched to force a landing in Minsk, the country’s capital, and Protasevich and his girlfriend were taken off the flight.

Applebaum describes the incident as having “no exact precedent,” shattering the illusion that individuals in the democratic world are insulated from autocratic threats. Protasevich’s kidnapping ultimately challenged the belief that democratic systems can “protect anyone who lives in them from the lawlessness that prevails in (countries like) Russia or Cuba.”

Autocracies “keep track of one another’s defeats and victories, timing their own moves to create maximum chaos,” explains Applebaum. In the fall of 2023, Applebaum writes, amid the bolstered discourse of “Ukraine fatigue,” the long-standing conflict between Azerbaijan and Armenia reignited as Azerbaijan launched a military offensive on Nagorno-Karabakh, which had already been under a blockade for the past year. In the Middle East, Iranian-backed Hamas militants perpetrated a terrorist attack against Israel that resulted in over 1,000 fatalities and started a new escalation that killed 45,000 people in Palestine.

Numerous other conflicts have flared up since the start of Russia’s full-scale war against Ukraine nearly three years ago. As Applebaum notes, “this multifaceted, interconnected, self-reinforcing polycrisis was not coordinated by a single mastermind, and it is not evidence of a secret conspiracy. Instead, these episodes, taken together, demonstrate how different autocracies have extended their influence across different political, economic, military, and informational spheres.”

Meanwhile, autocracies exploit loopholes in the financial systems of democratic countries, benefiting financially from the very countries they are working to undermine. Autocracies also continue to infiltrate information spaces within democratic societies, aiming to sow seeds of doubt and discord.

This includes the “fantastical tales of biological warfare (that) began to surge across the internet” following Russia's invasion of Ukraine. The Russian Defense and Foreign Ministries alleged that the U.S. had funded laboratories in Ukraine where experiments on viruses were purportedly being conducted. Although these claims were easily debunked, they proliferated rapidly on platforms like X and formerly Twitter and also gained traction elsewhere, such as in Chinese state media.

“China had a clear interest in this story, since it muddied recent history and helped relieve China of the need to investigate its own hazardous biolabs, including the one in Wuhan that might have been the true source of the COVID-19 pandemic,” Applebaum explains.

Even some independent news sites have amplified blatant disinformation. However, as Applebaum explains, many operate as "information laundromats," disguising themselves as media outlets when their purpose is to disseminate Russian talking points.

Readers may find themselves overwhelmed while reading “Autocracy, Inc.” — and justifiably so. In her 2021 article for The Atlantic which partly inspired this book, Applebaum didn’t mince words, warning that “the bad guys are winning.” She paints a grim picture of a possible future where international human rights are no longer guaranteed, and global conflict becomes the norm. At the same time, Applebaum points out that democracies cannot completely sever ties with these autocratic regimes, as cooperation will still be necessary on critical issues like climate change.

Yet, despite these challenges, Applebaum maintains an optimistic outlook and advocates for strategies to confront and counter the rise of global autocracy. These solutions are far from simple – if they were, notes Applebaum, they would have been implemented long ago.

Applebaum proposes that the solutions she lays out in the book be taken on by coalitions of countries that can be more effective in achieving goals such as working toward eliminating any loopholes that allow for money laundering and dark money. She also calls for undermining the information war rather than engaging in direct confrontation. A key part of this strategy is ensuring the information system — given its power over public perception — functions under strong laws and regulations, similar to the financial system.

“Since we first encountered Russian disinformation inside our own societies,” Applebaum writes, “we’ve imagined that our existing forms of communication could beat it without any special effort. But no one who studies autocratic propaganda believes that fact-checking or even swift reactions are sufficient. By the time the correction is made, the falsehood has already traveled around the world.”

Applebaum also warns against relying too heavily on trade with autocratic countries like Russia and China, calling it an "existential" threat. She recalls Europe’s dependence on Russian gas and explains how after Russia's full-scale war against Ukraine, the switch to more expensive energy sources triggered inflation. Russia then amplified the crisis through the spread of disinformation, fueling support for far-right movements in countries like Germany.

For those living comfortably in democratic societies, the dangers posed by countries like Russia might feel distant. However, North Korean troops supporting Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, as well as Iranian drones and missiles with China-supplied components being used to attack Ukrainian infrastructure underscore how this war is not some isolated event. Ukraine's struggle is not just a fight against Russia — it is emblematic of a larger battle for global democratic values, serving as a wake-up call for the world. As complacency risks setting in among democratic nations, the price of inaction might grow ever steeper.

Note from the author:

Hi, this is Kate Tsurkan, thanks for reading this article. There is an ever-increasing amount of books about Russia, Ukraine, and the greater region available to English-language readers, and I hope my recommendations prove useful when it comes to your next trip to the bookstore. If you like reading about this sort of thing, please consider supporting The Kyiv Independent.