Blinken praises how US handled Ukraine war, but were all calls “right”?

While the Biden administration prepares to depart from the White House, and US President-elect Donald Trump gears up to take office on 20 January, the New York Times has published an interview with Anthony Blinken, the outgoing Secretary of State.

One of the key figures in managing the Russo-Ukraine war, known for his diplomatic skill and light-hearted humor, he has largely been perceived well in Ukraine, which he visited on seven occasions in total.

Dubbed Anthony Blinken insists he and Biden made the right calls, his lengthy interview offers an overview of what happened over the years, with Blinken revealing some information while also making statements whose veracity and appropriateness are questionable.

I analyze the key points of his interview concerning Ukraine and provide commentary on them.

The Russo-Ukraine war at large

While avoiding the rabbit holes of Afghanistan and other foreign policy issues, at a minimum, Blinken’s overarching belief that “the right calls” were made by the outgoing administration in Ukraine is hardly the message that resonates with many Ukrainians who are now entering the third year of the full-scale invasion with no end of bloodshed in sight and even turning Trump-positive.

Blinken claims that the US quietly supplied Stringers and Javelins in September 2021 and December 2021 “that were instrumental in preventing Russia from taking Kyiv, from rolling over the country, erasing it from the map, and indeed pushing the Russians back.”

I can’t immediately verify this revelation, but even if true, it doesn’t change the overall macabre of the early days of the full invasion, as well as the massive exodus of all diplomatic institutions, including the US Embassy, in the winter of 2021-2022 followed by months of refusal to supply the so-called offensive weapons for Ukraine not just to defend itself against a total collapse but also quickly recapture the land.

The situation indeed eventually changed, with Ukraine receiving large bipartisan support in the early days of the invasion and the US and partners supplying heavy weaponry like HIMARS. These calls, late though right and deserving the highest appraisal, allowed Ukraine to quickly liberate the Russian-captured land, including the only regional capital Russia managed to seize since 2022, the city of Kherson, in November 2022.

The battlefield reality shifted dramatically in 2023 when the Russians started to build fortifications in the occupied territory and changed their tactics. The incursion of Iran’s proxy Hamas into Israel, launched in October 2023, only served to complicate the matter as Israel relies on US aid as well, while Ukraine had received ammo destined for it before that.

Since the failed 2023 counteroffensive, Ukraine has been on a losing streak – with the exception of its highly classified incursion into Kursk Oblast, which proved to be a success.

The Biden administration’s decisions that followed ranged from questionable to disappointing, with bipartisan support decreasing as the pivotal question started to emerge: what is the end goal of the war?

The answer was never explicitly provided, but if the Biden administration’s rejection of the Victory Plan in the fall of 2024, its leak of classified information to the press, and its provision of only 10% of promised aid in 2024 are anything to go by, it is most certainly not Ukraine’s victory.

Diplomacy efforts

Speaking about his diplomatic efforts, Blinken states, “I worked very hard in the lead-up to the war, including meetings with my Russian counterpart, Sergey Lavrov, in Geneva a couple of months before the war, trying to find a way to see if we could prevent it, trying to test the proposition whether this was really about Russia’s concerns for its security, concerns somehow about Ukraine and the threat that it posed, or NATO and the threat that it posed, or whether this was about what it in fact it is about, which is Putin’s imperial ambitions and the desire to recreate a greater Russia, to subsume Ukraine back into Russia. But we had to test that proposition.”

This is true. The Biden administration and Blinken personally engaged with Russia extensively in the winter of 2021-2022.

Russia also held a bilateral meeting with NATO in January 2022, with one NATO source describing that meeting off-record as absolutely futile, saying that the Russians just kept repeating the same old narratives against the unrealistic ultimatum toward NATO and the US never to include Ukraine, undo the post-1997 NATO enlargement by removing the troops and weapons stationed there, and not to admit new members, especially the ex-Soviet states.

It was predictably rejected, and Russia launched the multi-vector invasion.

The diplomatic efforts that ensued from the full-scale invasion, which Blinken mentions in the interview by saying that they brought and kept together more than 50 countries, deserve credit. The Biden administration and Blinken did a solid job of putting pressure on many countries that were either unfavorable to Ukraine from the outset or were hoping for the war to end quickly and for business as usual to resume. This foremost includes Germany, where some voices advocated the launch of the now-defunct Putin’s pet project, the Nord Stream 2 pipeline, even after 24 February 2022.

Blinken goes on to state, “Since then, had there been any opportunity to engage diplomatically in a way that could end the war on just and durable terms, we would have been the first to seize them. Unfortunately, at least until this moment, we haven’t seen any signs that Russia has been genuinely prepared to engage. I hope that that changes.”

Indeed, there are very few signs that Russia is prepared to engage in any peace push, even with Trump’s administration. Especially since the sanctions, while not being completely ineffective, have not managed to cripple the Russian war machine or economy to the fullest.

The population of Saint Petersburg and Moscow does not feel the ramifications of the war to the extent necessary. At the same time, Russia’s partners North Korea and Iran proved to be much more responsive, with Pyongyang even providing their troops for Russia to liberate Kursk Oblast.

On weapons, including nuclear ones

In other parts of the interview, Blinken comments on the general management of the Russo-Ukraine war, acknowledging “that there’ve been different moments where we had real concerns about actions that Russia might take, including even potentially the use of nuclear weapons,” adding that, “I think throughout we’ve been able to navigate this in a way that has kept us away from direct conflict with Russia.”

He doesn’t clarify, nor is he asked to clarify, what this “in a way” refers to. There’s, however, reason to believe that he’s referring to the so-called escalation management policy, designed by Biden’s national security advisor, Jake Sullivan. In a nutshell, it follows the logic of helping but in a very minimized way in order to not provoke the adversary, in this case, for it to not push the button.

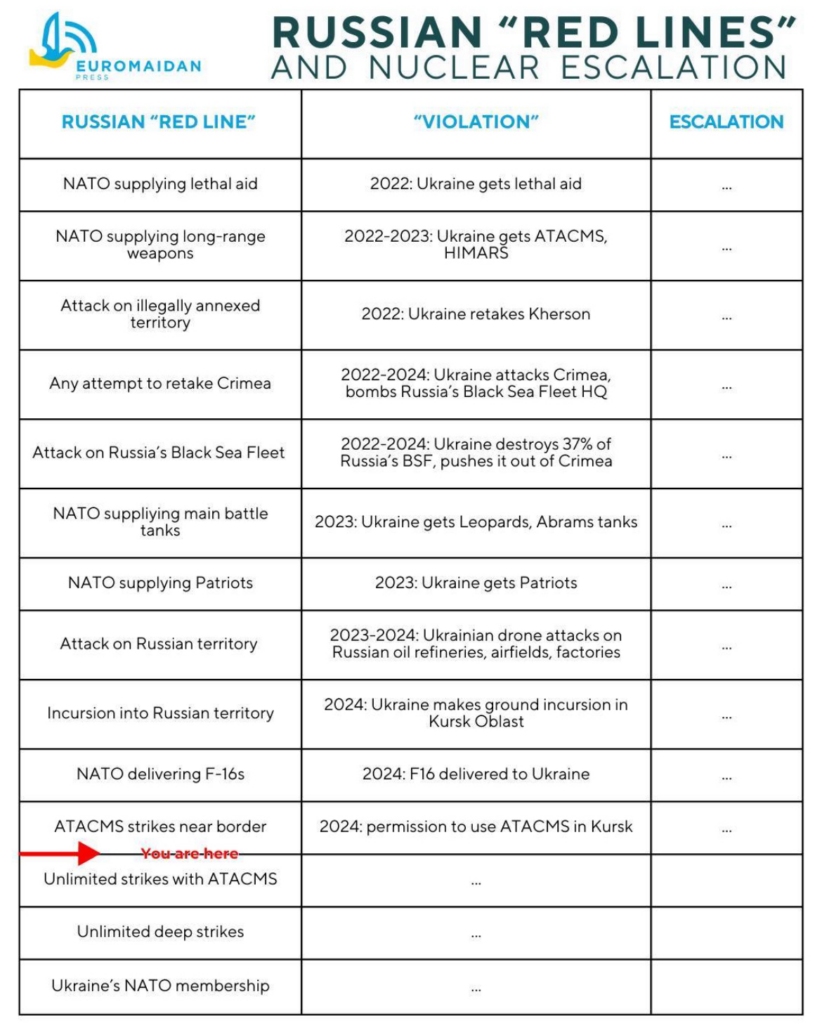

Understandable at a glance, it is not entirely clear why the threat persisted given the number of “red lines” crossed by Ukraine and its partners since 24 February 2022 and the fact that both the US, by its own admission, and likely China, by Blinken’s admission to the FT, warned Russia against doing it and it discarded the plans accordingly.

He states, “But I think what’s so important to understand is at different points in time, people get focused on one weapon system or another. Is it an Abrams tank? Is it an F-16? What we’ve had to look at each and every time is not only should we give this to the Ukrainians but do they know how to use it? Can they maintain it? Is it part of a coherent plan? All of those things factored into the decisions we made on what to give them and when to give it.”

Even if true in parts, this remains misleading.

When Ukraine asked, if not to say begged, for the Patriots systems in late 2022 when Russia started pounding Ukraine’s power grid, a scenario that had been widely anticipated, there was no justification as to why Washington D.C. refused to deliver them. I happened to be a witness to that in Bucharest, where Blinken attended the NATO foreign minister’s summit in 2022.

Similarly, no explanation was ever provided as to how one can seriously expect Ukraine, even with the help of other countries, to counter Russia with 31 Abrams tanks and 190 Bradleys, provided to it alongside other weaponry in 2023, to liberate its land from the strengthened enemy who rearms faster. Especially without the air superiority.

There’s likewise no reasonable argument as to the timing of some decisions.

Why were F-16s not a good idea in early 2023 but became acceptable in September 2023?

Or why was it ok to lift the long-range strikes cap in November 2024 but not in August 2024, for example, when Ukraine invaded and occupied Russia’s sovereign territory?

Ukraine peace talks

Asked how he feels about leaving Ukraine in the current stagnating position, not knowing what’s next, he answers: “Well, first, what we’ve left is Ukraine, which was not self-evident because Putin’s ambition was to erase it from the map. We stopped that. Putin has failed. Ukraine is standing.”

Undoubtedly, he’s right. Without the help of the US and the allies, Ukraine, regardless of the bravery and resolve of its people, would not have withstood the Russian aggression, especially since it had not taken the steps necessary to prepare for an invasion of this scale.

However, his answer to the question of whether “do you think it’s time to end the war, though?” offers a different angle: “These are decisions for Ukrainians to make. They have to decide where their future is and how they want to get there. Where the line is drawn on the map at this point, I don’t think is fundamentally going to change very much.”

This is largely in line with what the Ukrainian voices, including those based in Washington D.C., have been communicating since the summer of 2024, emphasizing that the Biden administration is willing for Ukraine to negotiate but wants to do so at Kyiv’s request.

Naturally, any negotiation in a position where the defending party has not attained its goals would involve some concessions, foremost territorial ones.

His answer to the next question of whether he feels the territory will have to be ceded to Russia plays into this notion: “Ceded is not the question. The question is the line, as a practical matter in the foreseeable future, is unlikely to move very much. Ukraine’s claim on that territory will always, always be there.”

He goes on to rightly ask rhetorically if Ukraine “will find ways with the support of others to regain territory that’s been lost?” and states that it’s “unlikely that Putin will give up on his ambitions.”

“If there’s a cease-fire, then, in Putin’s mind, the cease-fire is likely to give him time to rest, to refit, to reattack at some point in the future. So what’s going to be critical to make sure that any cease-fire that comes about is actually enduring is to make sure that Ukraine has the capacity going forward to deter further aggression,” he adds.

“We put Ukraine on a NATO membership path”

So, how does one deter that aggression that is almost guaranteed to happen once again as Russia has proved to systematically violate agreements it signs?

Blinken answers, “That can come in many forms. It could come through NATO, and we put Ukraine on a path to NATO membership. It could come through security assurances, commitments, and guarantees by different countries to make sure that Russia knows that if it reattacks, it’s going to have a big problem.”

First, “we put Ukraine on a path to NATO membership” is a highly misleading statement.

It was George W. Bush’s Republican administration that did this. He was the only American president to openly endorse Ukraine’s NATO membership in 2008 at the now infamous Bucharest summit, with the then-Chancellor Angela Merkel and then-President of France Nicolas Sarkozy blocking it and instead pledging that “Ukraine and Georgia will become NATO member states.”

Four months later, Russia invaded Georgia, occupying 20% of its territory to this day.

Ukraine’s NATO membership was put on ice by the subsequent Barack Obama administration and later by Donald Trump when the Allies refused to issue so much as a Membership Action Plan, let alone an invitation.

Joe Biden did not change anything in this respect except for the wording of the joint communiques. While Finland and Sweden were welcomed into the Alliance within a span of 2 years, Ukraine’s official application submitted in September 2022 was snubbed.

The two NATO summits in Vilnius and Washington D.C. failed to produce any specific timelines or invitations, with Biden stating in his interview with the Times in June 2022 that he doesn’t support Ukraine’s NATO membership.

As of today, Ukraine’s NATO prospect remains as ephemeral as ever, as evidenced by public and off-the-record statements, even though it is still the highly preferable option for Ukraine.

As for the security guarantees and other types of commitments, while Blinken doesn’t deep-dive into that, he’s right that regardless of NATO, Ukraine simply has no choice but to develop its own defense model in the foreseeable future. What it will look like depends foremost on Ukraine, and will have to learn from the experience of others, especially Israel.

Lastly, he adds that he hopes that the US “will remain the vital supporter that it’s been for Ukraine, because, again, this is not just about Ukraine. It’s never just been about Ukraine.”

Undoubtedly, he’s right.