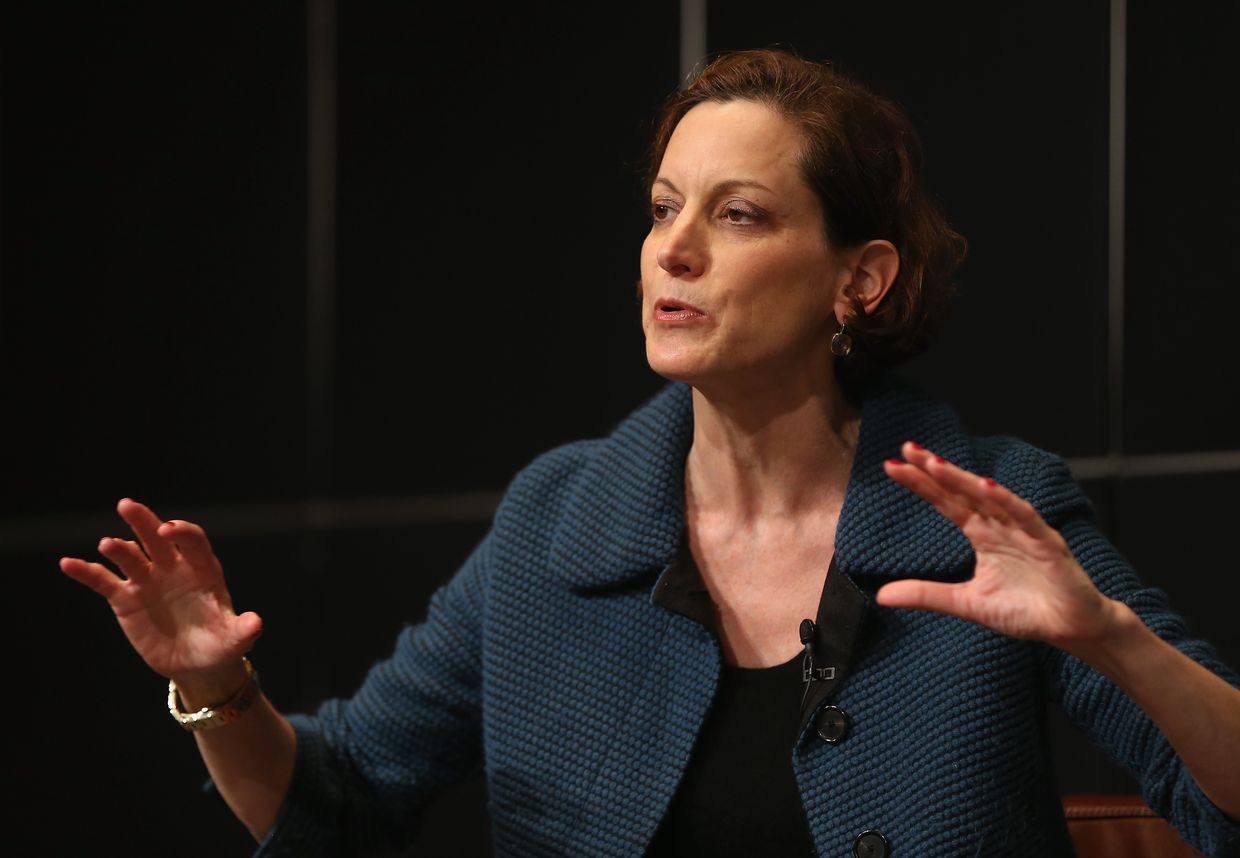

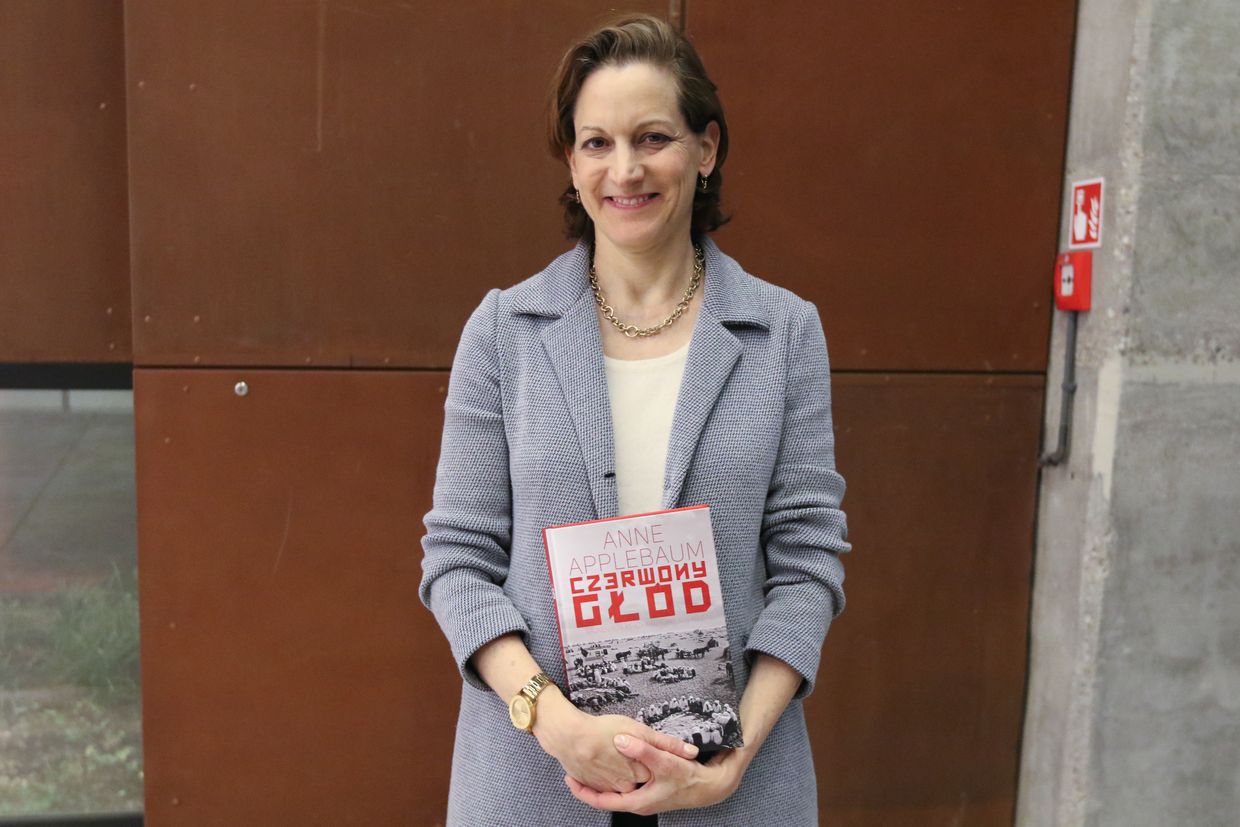

Anne Applebaum: Russia is ‘one of the world’s most unstable autocracies’

Democratic nations have grappled with a range of pressing issues in recent years, including the inherent flaws of long-established political systems, the erosion of international alliances, and global economic challenges, all while autocracies have been gaining power by exploiting this instability.

American journalist and historian Anne Applebaum’s latest book, “Autocracy, Inc.,” delves into the complex mechanisms that underpin autocratic regimes, highlighting the roles of financial networks, surveillance technologies, and propagandists who bolster their narratives of power and control.

Unlike the ideologically motivated autocrats of the Cold War era, today's authoritarian leaders, Applebaum argues, are driven solely by the pursuit of power. Unfazed by Western sanctions, countries like Russia, China, North Korea, Iran, and Venezuela form alliances to mutually support each other's financial, security, and political objectives. Russia, North Korea, and Iran are even being called by some the new “Axis of Evil.”

In this context, maintaining an optimistic outlook can seem daunting. However, Applebaum underscores not only the urgent necessity of defending democracies against the rise of authoritarianism but also offers effective strategies for doing so.

The Kyiv Independent recently spoke with Applebaum about the rise of autocracies and potential strategies the West can employ to counteract them.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The Kyiv Independent: In "Autocracy, Inc.," you detail how Russia has been a leader in merging autocracy with kleptocracy, creating a network of states that support and economically sustain one another in the face of international sanctions. Given the scale of this system Russia has helped put in place, do you think we are facing the long-term threat of an autocratic Russia even after Vladimir Putin’s eventual demise?

Anne Applebaum: I’d hesitate to make any predictions about Russia’s long-term future. Not only do we not know who might succeed Putin, but we also don't know how that successor would be chosen. In a sense, Russia stands out as one of the world’s most unstable autocracies.

In China, the Communist Party will select the next leader, and in Iran, a religious council stands behind the government. We know how these systems work. But in Russia, it doesn't really function as a system anymore – Russia is essentially a one-man state.

It’s true that the autocratic system Russia has created has had a significant global impact, with many countries having imitated it. What used to be ordinary corruption has become financialized, allowing massive sums of money to be hidden. Autocrats can now turn political power into enormous wealth, becoming billionaires. This pattern, set by Russia, has been highly influential.

It will likely persist beyond Putin, and it will continue until there’s a way to challenge or counteract it. But as for what will happen to Russia after Putin’s gone, that remains uncertain.

The Kyiv Independent: One point in the book that really struck me is when you wrote that no country has autocracy in its “genetic code.” I think that it’s important to remember this because looking at a country as irredeemably undemocratic, one might argue, could inadvertently bolster an autocrat's power. However, given the multitude of conflicts in recent years, how should democracies engage with autocracies like Russia and China in the future?

Anne Applebaum: We need to think much more strategically about how we trade with these countries. Autocracies aim to leverage our technology and economic ties to exert influence within our countries. The idea that the economy is a neutral space without significant implications is one we need to abandon.

It's crucial to understand this, but I’m not advocating for cutting off all relations with these autocracies – that's neither realistic nor practical. There are important discussions to have with autocratic governments, whether related to trade, climate change, or urgent crises. We can't ignore their existence.

However, understanding their worldview is key in protecting our democracries. The goal of my book is to explain that they see themselves in a constant conflict with us, and we need to recognize this and respond accordingly.

The Kyiv Independent: We’ve seen growing frustration concerning international institutions like the U.N., which continue to engage with Russia as usual, even as it commits war crimes. In that sense, has the international rules-based order thought up after World War II already failed us, and if so, does it need to be radically rethought?

Anne Applebaum: It failed some time ago, actually. The so-called international order has always been more aspirational than real. The U.N. Convention on Genocide didn't prevent the genocide in Rwanda, for example. Similarly, there are international laws against torture, but that hasn’t stopped torture from being used in dozens of countries since 1945. These laws exist as ideals to strive for rather than guarantees.

That said, some nations do take these standards seriously. When U.S. soldiers were accused of torturing Iraqi prisoners, they were court-martialed and went to prison. So, while some countries enforce these laws, many others do not.

In my view, the U.N. system is beyond saving or rebuilding. It's a very 20th-century institution rooted in the belief that large bureaucracies based in places like New York or Geneva can solve global problems. This mindset reflects the world of the 1950s, but it's outdated. Instead, I would much prefer to see coalitions of countries wanting to solve specific issues.

Take kleptocracy, for example. A group of 100 nations could come together to tackle offshore tax havens, anonymous companies, and money laundering. If these countries committed to the cause, they could create a meaningful plan to combat these problems. That’s the kind of coalition worth building and focusing on moving forward.

"I don't believe a massive organization that includes Russia, China, Togo, Sierra Leone, and the U.S. is capable of solving international issues effectively."

I don't believe a massive organization that includes Russia, China, Togo, Sierra Leone, and the U.S. is capable of solving international issues effectively.

The Kyiv Independent: Considering the extent to which individuals within these very financial systems benefit, along with the complexities of a globalized economy, how feasible do you think these reforms are in our lifetime?

Anne Applebaum: We’re already seeing some changes in both the U.S. and the U.K. Significant progress has been made toward eliminating anonymous companies. In the U.K., both the prime minister and the foreign minister have given speeches addressing this issue, showing a clear desire to tackle it.

There’s a growing political will to push back against these practices, so I don't think it's an impossible task. Of course, much depends on the outcome of the next U.S. election. Kamala Harris, for example, has a background as a prosecutor and a strong interest in the rule of law, so she might champion this issue. The Biden administration has already made some progress.

Obviously, if Donald Trump wins, things could go in the opposite direction. He has personally benefited from the offshore kleptocratic world — this was part of his business model. A significant portion, perhaps a fifth, of the apartments in Trump-named buildings were bought by anonymous companies. We don't know who the real owners are, but many likely come from Russia, China, or other autocratic nations, possibly using these purchases for money laundering.

Secrecy is a hallmark of autocracies. We don't know the sources of wealth for leaders like Xi Jinping or Vladimir Putin, and this opacity is deliberate. That said, I believe it's possible to eliminate these practices. It will require a coalition of willing nations and a gathering of political will, but signs of that momentum are already visible.

"Secrecy is a hallmark of autocracies."

The Kyiv Independent: Many individuals, frankly speaking, seem uninterested in the developments occurring in countries like Russia, China, Venezuela, and Iran, and the threats they represent, leading to a lack of urgency among the populaces of democracies. Unfortunately, democratic leaders have not effectively communicated these threats, which enables bad actors to mock and exaggerate concerns, such as the potential for Russian interference in U.S. elections. How can we better communicate to people that these threats are more interconnected than one might realize?

Anne Applebaum: First, they would need to truly understand the issue, and I’m not sure all of them do. They’d also have to make it a priority. Foreign policy issues rarely take center stage in domestic election campaigns, so it’s important to find a way to make them relevant.

That’s why, in my book, I focused on how autocratic practices are impacting us directly and influencing our internal politics. I believe that framing it this way is key to convincing people of its importance.

I also recently co-produced a podcast with Peter Pomerantsev, who writes extensively about Ukraine. The podcast, “Autocracy in America,” explores how autocratic practices are present in the U.S. itself, aiming to engage American voters on this issue. It’s all about finding new ways to connect with people and raise awareness.

The Kyiv Independent: In “Autocracy, Inc.,” you describe how authoritarian regimes frequently co-opt the language of independent media to present themselves as legitimate sources of information. Still, they spread disinformation that, in the internet age, quickly goes viral. Looking ahead, what strategies can democratic nations adopt to fortify their information ecosystems against such tactics? Is there anything that makes a democratic society more susceptible to propaganda and disinformation?

Anne Applebaum: This is a complex issue, and at its core, it involves regulating social media. I don't see a solution without doing that. People like Maria Ressa have tried creating online networks to counter propaganda, but even she seems to have concluded that regulation is the only real answer. By regulation, I don’t mean censorship – I mean holding social media platforms legally responsible for the content on their sites.

In the U.S., Section 230 currently protects platforms from being held liable for what users post, unlike newspapers or TV companies, which are responsible for what they publish. I believe we will eventually need to change that law, and I hope we’ll see progress on this under a future administration, perhaps under Harris.

To illustrate, if a bank were found to be funding terrorism or enabling the sale of child pornography, we wouldn't hesitate to hold the CEO accountable — those actions are clearly illegal. Yet, somehow, internet platforms continue to avoid such accountability. It's time to change that.

The Kyiv Independent: You dedicate “Autocracy, Inc.” to the optimists. In a world where authoritarianism is on the rise, what does it mean to be an optimist, and how can such optimism be sustained in the face of these growing threats?

Anne Applebaum: It's important to remember that history is not predetermined. There’s nothing that guarantees democracy will fail, autocracy will succeed, or vice versa. We aren’t promised victory in the end – that's not how it works.

The optimistic view is that what we do today directly shapes what happens tomorrow. Each of us has the power to influence and change the world, to make a difference. Recognizing that we have this agency is what should give us hope.