He fought Putin’s prisons for 10 years

“The situation we found ourselves in February 2022, put us at a crossroads: either allow the destruction of our freedom, or fight.“

For two decades, prominent journalist and human rights activist Maksym Butkevych had established himself as one of Ukraine’s most formidable voices for justice.

In the first days of the full-scale Russian invasion, one of Eastern Europe’s most respected human rights advocates stepped up to defend his principles with a rifle.

Months later, the tables turned: he was sentenced to 13 years in the very same Russian prison system he had once helped free others from, convicted of crimes he never committed.

For two and a half years, Butkevych remained one of the war’s most high-profile POWs—caught between Kyiv’s relentless campaign for his freedom and Moscow’s grip on his cell.

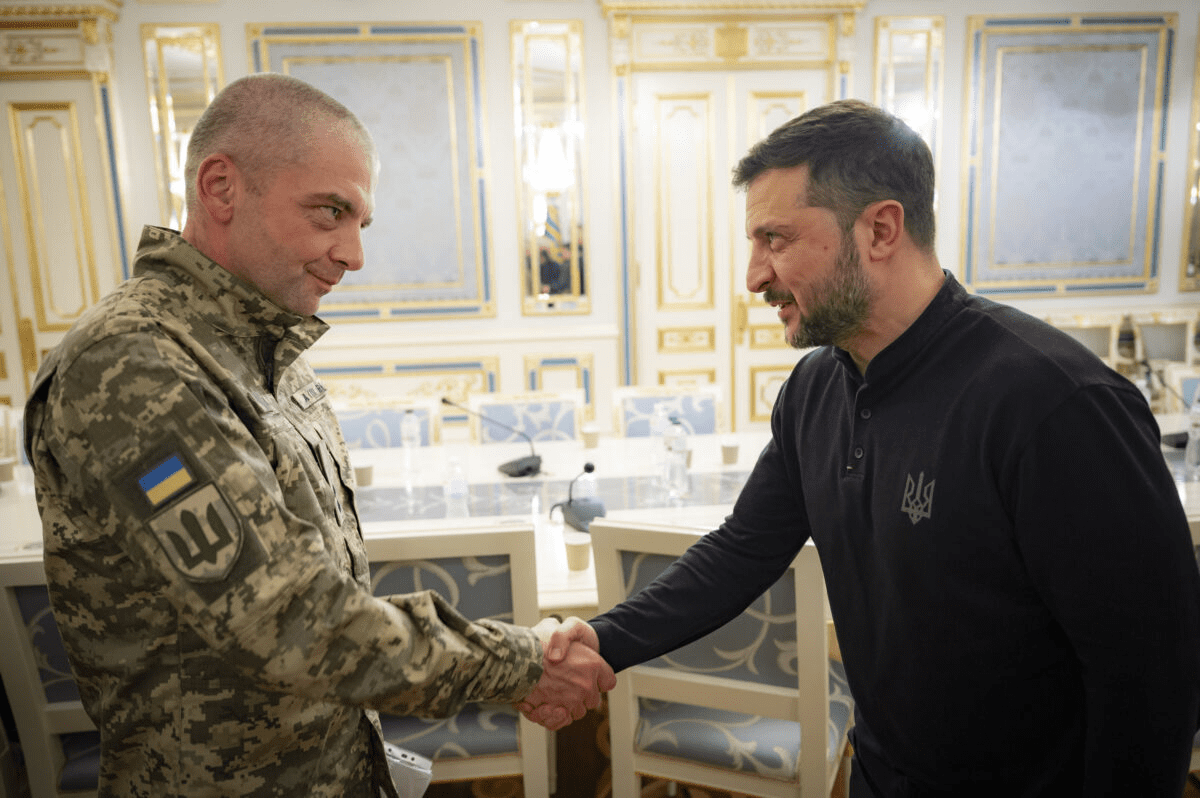

On 18 October 2024, Ukraine’s battle for his release paid off: Maksym Butkevych walked free in a prisoner exchange with Russia, marking the end of a battle that had galvanized Ukraine’s civic society for 913 days.

In his first major interview with ZMINA Human Rights Center—a leading Ukraine’s human rights NGO he helped create—Butkevych breaks down his shift from rights defender to soldier, maps Russia’s prison system from behind bars, and exposes the reality for thousands of Ukrainian POWs still held captive.

The architect of Ukraine’s civic society

Before the full-scale war, Maksym Butkevych was well-known for his work in independent journalism and human rights advocacy. His biography includes work with the BBC Ukrainian Service in London, where he produced programs on art and refugee issues, serving on the board of Amnesty International’s Ukrainian branch, and leading communications for the UN Refugee Agency.

In the early 2010s, Butkevych emerged as one of the key architects of Ukraine’s civil society during the authoritarian rule of the Russian-backed dictator Yanukovych, a period marked by a severe crackdown on human rights in Ukraine.

In 2012, Butkevych co-founded ZMINA Human Rights Center, which rose to become one of Ukraine’s leading NGOs, documenting 8,500 Russian human rights violations during the full-scale war.

During the 2013 Revolution of Dignity, that drove Yanukovych to flee to Russia, Butkevych co-founded Hromadske Radio—a public, non-commercial broadcaster that emerged from journalists’ fight for integrity and grew into a major platform with up to a million monthly visitors.

Since the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2014, Butkevych’s human rights activism has taken on a new dimension—fighting for the release of Ukrainian political prisoners in Russia. As a leading member of the Committee for Solidarity with Kremlin Hostages, he helped secure the release of several high-profile detainees, including the widely publicized case of Ukrainian filmmaker Oleg Sentsov.

With nearly 20 years of human rights work under his belt — from co-founding “Without Borders” to combat racism in Ukraine to securing the release of Russia’s political prisoners — Butkevych built a reputation as a steadfast pacifist.

That’s why many were stunned when, on the first day of the full-scale war, he took up arms to continue his human rights mission.

“I’m really not in favour of violence as a method, and military service, in one way or another, involves taking lives. It’s undoubtedly a problem and a moral-ethical dilemma for me,” Butkevych told ZMINA.

The day a pacifist chose war

Butkevych explains that his decision to take up arms was a continuation of his human rights advocacy—his lifelong mission now at risk from the brutality of Russian occupation.

“I understood that if the Russians prevailed, there would be no more human rights protection in this territory,” he said. “We’ve fought long and hard for the rights we have today. But if they’d come to these territories, everything would have been destroyed.”

With no real combat experience and only decades-old university officer training, Butkevych reported to the conscription office on the first day of the full-scale war.

“I said I was a lieutenant after military training, but I didn’t remember anything from military service, I didn’t know or was skilled in anything. However, I was ready to grab a shovel and dig whatever was needed.”

That day, Russian forces had already seized Kyiv’s suburbs, with military vehicles advancing on the city’s outskirts. In the weeks that followed, Maksym Butkevych joined the Battle of Kyiv—the decisive campaign of the early full-scale war, which thwarted Russia’s plan to swiftly capture the capital, topple the government, and subjugate Ukraine within days.

Butkevych was right at the front, charging into the newly liberated Kyiv suburbs after weeks of Russian occupation.

“The locals welcomed us with tears in their eyes, bringing flowers, jars of tomato juice—whatever they had after a month of occupation. It was truly incredible. You could feel how much they had been waiting for us,” he recalls.

Later, Butkevych became part of the 210th Separate Special Battalion “Berlingo,” a volunteer unit formed in the war’s early days within the Presidential Regiment, charged with hunting down Russian heavy armored vehicles trying to capture the capital.

Once Kyiv’s safety was secured, the unit was deployed to reinforce Ukrainian forces in the east, tasked with halting the Russian push into Donbas.

With a group of soldiers now under his command, Maksym Butkevych found himself in open fields, stripping away their urban combat advantages and forcing his unit to quickly adapt to conventional ground warfare tactics.

Betrayed by a rescue call

In June 2022, Butkevych’s unit received orders to move to a village in the Luhansk region with challenging terrain of forests and ravines. Upon arrival, they endured intense mortar shelling throughout the night that left the village largely wiped out by morning.

The situation rapidly worsened. Russian electronic warfare jammed their communications, and in the sweltering June heat, they ran out of water. By morning, with no radio contact, they spotted large enemy forces and equipment marked with Russian tactical insignia.

Butkevych realized they were effectively in a “bottleneck”, with their position surrounded by enemy-controlled territory. The final trap was sprung when a soldier from a neighboring unit contacted them, claiming there was still a way out of the encirclement.

Exhausted from days without sleep and nearly a day without water, they followed his directions across an open field toward a tree line.

The soldier fired a flare—an oddly conspicuous action in enemy territory. When they were just meters from the forest, the soldier revealed that he had been captured the previous evening, and they were now under Russian guns—they would have to surrender or be killed.

With his eight men exposed in the open field, Butkevych had no choice but to surrender.

“There was nowhere to take cover, hide, or run,” Butkevych recalls. “I had eight men under my command, and I was responsible for them. So I gave the order to lay down our weapons.”

The soldier who led them to surrender was later held in the same cell. He had been forced to cooperate through violence, believing—as the Russians told him—that he was actually saving comrades’ lives by making them surrender.

“Perhaps he was right—it’s hard for me to judge,” Butkevych says.

The art of prisoner humiliation

The journalist reveals that the moment of capture marked the start of a brutal process of dispossession. The Russians quickly seized their documents, phones, and personal belongings.

“When you’re on your knees with your hands tied and a gun pointed at you, you’d generally give anything away,” he says.

Butkevych recalls a Russian soldier demanding his wireless earphones as a “gift.” He refused, explaining that they were a present from someone close to him. The soldier’s confusion revealed much about the dynamics at play.

“They were trying to avoid acknowledging that they were stealing from prisoners,” the activist reflects. “I suggested he might need to call it a ‘trophy’ or find some other euphemism for what it really was.”

The pattern of dispossession persisted at each checkpoint, with soldiers seizing whatever they had left—watches, body armor, and even their shoes.

“They also took a bulletproof vest from a soldier who still had one, asking him not to mention it to their commanders. From what we understood, theirs were in worse condition at the time,” Butkevych recalls. ”We spent the next few months only in socks.”

By the end of that first day, the prisoners found themselves in a semi-destroyed building, spending the night on a concrete floor. The guards allowed them to use their hands only when, one by one, and at gunpoint, they were permitted to use a makeshift toilet—a plastic barrel cut off at the top, standing in the corner.

One of the most unsettling aspects of the initial captivity was the psychological torture, which began on their first day in Russian custody, setting the tone for the torment that would last for the next years.

“At one point, an officer in a balaclava appeared, taking charge, and everyone fell in line. He forced us to kneel with our hands tied behind our backs and started […] verbally mocking us to assert his supposed superiority,” the journalist says.

He recalled how a Russian officer would deliberately target prisoners whose wives had evacuated abroad, taunting them with graphic descriptions of sexual violence allegedly committed against their spouses. The prisoners were also threatened with decades-long sentences in colonies where they would face sexual abuse.

Maksym Butkevych’s reveals that, initially, his status as an officer and his pre-war work as a journalist and human rights defender didn’t significantly affect his treatment. At a transit point, he identified himself when the Russians asked who among them was an officer.

They tried to film him criticizing his command, but he refused, making it clear that any forced statements would be obvious as coerced.

However, as the interrogations began, captured on camera, the situation shifted dramatically, and the torture became brutal and overt. After one soldier was struck with a wooden hook for failing to recall commanders’ call signs, Butkevych advised his men to be open about non-sensitive details while steering the more provocative questions toward himself.

“Since we didn’t have any secret information, I told the guys to tell everything during interrogations to preserve themselves,” he recalls.

The culmination of these early days came when they were transferred to a pre-trial detention center in Russian-occupied Luhansk. Butkevych remembers that they removed their blindfolds and untied their hands, and they found themselves in a cell.

“They brought old, torn mattresses and towels. Some had the Luhansk detention center stamp – that’s how we learned where we were.”

This facility would become his home for the next year and three months, until September 2023.

Making war criminals the Russian way

In March 2023, an occupation court in Luhansk sentenced Butkevych to 13 years in prison for “cruel treatment of civilians and use of prohibited methods in armed conflict,” making him one of nearly 200 Ukrainian POWs sentenced by Russia on fabricated charges.

The path to this verdict revealed much about the occupation authorities’ methods of extracting confessions and fabricating evidence. During his time in the Luhansk pre-trial detention center, Butkevych faced interrogations from various entities—both uniformed personnel and civilians in plain clothes.

“They questioned us about our unit’s movements, specific locations, dates,” he recalls.

One particular interrogation on 16 July took an unexpected turn when investigators showed special interest in the Soros Foundation’s activities in Ukraine, pressing him to give an interview to an unnamed “respected international media outlet.”

“I told them I didn’t want to give any interviews,” Butkevych says, “but if forced, I could only tell what I knew – about the foundation’s support for decentralization projects, local governance, legal aid, and academic publications.”

This response earned him his first direct threat: imprisonment.

On 13 August, it turned into reality when masked interrogators forced him into a painful position, unable to see anything but the floor, as they relentlessly tried to break his composure.

They presented him with three increasingly menacing options: sign a confession to war crimes without reading it, with the promise of an eventual exchange; refuse and face execution during a staged escape attempt in an “investigative experiment”; or remain imprisoned indefinitely with no hope of exchange.

“They told me that at 45, it might be time to end my life anyway,” the journalist recalls.

The charges were entirely fabricated. Butkevych later discovered they had accused him of launching grenades at a residential building, supposedly wounding two women. To cement the lie, they brought him to a supposed crime scene in Russian-occupied Sievierodonetsk, forcing him to pose at the building he allegedly attacked and memorize an address for a crime he never committed.

“The only thing I insisted on, as much as one could insist in that situation, was that I wouldn’t testify against others, only against myself, and that the case shouldn’t involve any deaths,” he reveals.

When the 13-year sentence was handed down, Butkevych remained certain he wouldn’t serve the full term, convinced that an exchange would eventually secure his release. While his cellmates were more optimistic about the outcome, he anticipated a sentence of 12 to 15 years.

A Russian investigator later exposed the cynical reasoning behind the lengthy sentences. Ukrainian soldiers were sentenced to long terms to match the penalties Ukraine imposed on Russian prisoners for “illegal border crossing with the intent to seize territory.” This strategy ensured Russian soldiers would be exchangeable.

Finding purpose behind bars

Reflecting on the source of his resilience in captivity, Maksym Butkevych credits his strength to his spiritual life.

“I have a sense of purpose that’s inseparable from the meaning of life, the meaning of salvation. Simply put, I feel none of this happened without reason,” he says.

He recalls rereading the New Testament and Psalter, which mysteriously found its way into their cell. He read it aloud to fellow inmates—many too injured or ill to read themselves—going through it at least 15 times.

During one interrogation, when pressed for his social media passwords, Butkevych revealed he had left his passwords with friends in case he was killed in action, so they could announce his death and set up automatic email responses.

However, despite making such preparations for death, he pointed out that most soldiers never gave a second thought to the possibility of being captured.

“Everyone who goes to the frontline mentally processes the possibility of being wounded or killed,” he explains. “But I barely saw anyone who considered what would happen if they were captured. We weren’t prepared for that.”

In captivity, Butkevych kept his mind sharp and his purpose intact. After a year and a half, when books were finally within reach, he devoured at least 50, using them to fuel his strength through the ordeal.

Perhaps most remarkably, Butkevych began teaching English to his fellow prisoners. With nothing but their resourcefulness to rely on—no paper, pens, or possessions—they made do with whatever materials they could scrounge.

“We used a cigarette filter, a burnt match, and pieces of cigarette packets to explain sentence structure. We learned through song lyrics I could remember,” Butkevych says.

Maksym Butkevych reveals that forced isolation and overwhelming psychological pressure often had a devastating impact on prisoner’s mental health. He recalls that the others would become overwhelmed, feeling that their time in captivity had been erased from their lives.

For him, however, captivity paradoxically provided the opportunity to reflect on issues he hadn’t had time for in civilian life.

“Looking back at my choices since the invasion began, I concluded I made no wrong choices. There are things I regret in life, but not in this chain of events,” he says.

Now, as Butkevych looks toward his future during his 30-day rehabilitation leave, he carries with him the lessons and insights gained during his imprisonment.

“I never doubted that people remembered me, that they were trying to secure my release, that they were thinking of me and praying for me,” he says.

While some of his fellow captives have been freed and one has tragically fallen in defense of Ukraine, many others remain in Russian custody, keeping Maksym Butkevych determined to use the lessons learned in captivity to fuel his ongoing human rights fight.

“I tried to understand what I could learn from this experience that might help me better serve others in the future,” he says.