What Syria means for Ukraine

I came to Ivan Franko University in Lviv for the first time in 2016 to teach Ukrainian students a course on Middle East politics. That year, I argued that Russia’s 2015 deployment in Syria was a rehearsal for a future war with Ukraine.

At that University I met the co-author of this article, Maria Marchenko, who would witness the aerial Russian tactics used in Syria against the northeastern Sumy Oblast, her home, as well as throughout Ukraine. During the lectures at the University, I discussed the Iranian-Russian alliance in Syria as well as the Iranian-produced kamikaze drone called Shahed, which means “witness” in Arabic and Persian. Indeed, upon her return, Maria witnessed how the “witness” had completely disrupted her life in Kyiv.

Syria had become a testing ground for Russian missiles that would be used in Ukraine as early as 2015 when it first intervened on behalf of Syrian regime leader Bashar al-Assad.

For example, from the fall of 2015 to the summer of 2016, Russia tested out long-range Kalibr cruise missiles over Syria, ostensibly against ISIS targets.

There were Russian planes stationed in Syria whose deployment would have been more accurate and effective in targeting ISIS, not to mention cheaper than using costly cruise missiles. However, an air raid would not have delivered the same political message for Putin.

The range of the cruise missiles launched from the Caspian Sea demonstrated to the US and NATO the advances in Russian military technology, more related to Moscow’s tensions with the West over Ukraine.

The 2015 missile attacks were documented by the Russian Ministry of Defence on YouTube, giving Russian citizens the chance to “like” these missiles of the nation’s arsenal in a show of post-modern missile nationalism. The video of the 2015 missile launches garnered nearly eight million views.

The Russians dropped munitions on Syria, devastating its towns and cities and forcing millions to flee as refugees as far as Europe. Those same bombs from the air would make Ukrainians into refugees, fleeing toward Europe. Indeed, Maria Marchenko was one of them fleeing to Italy.

The Guernica pattern

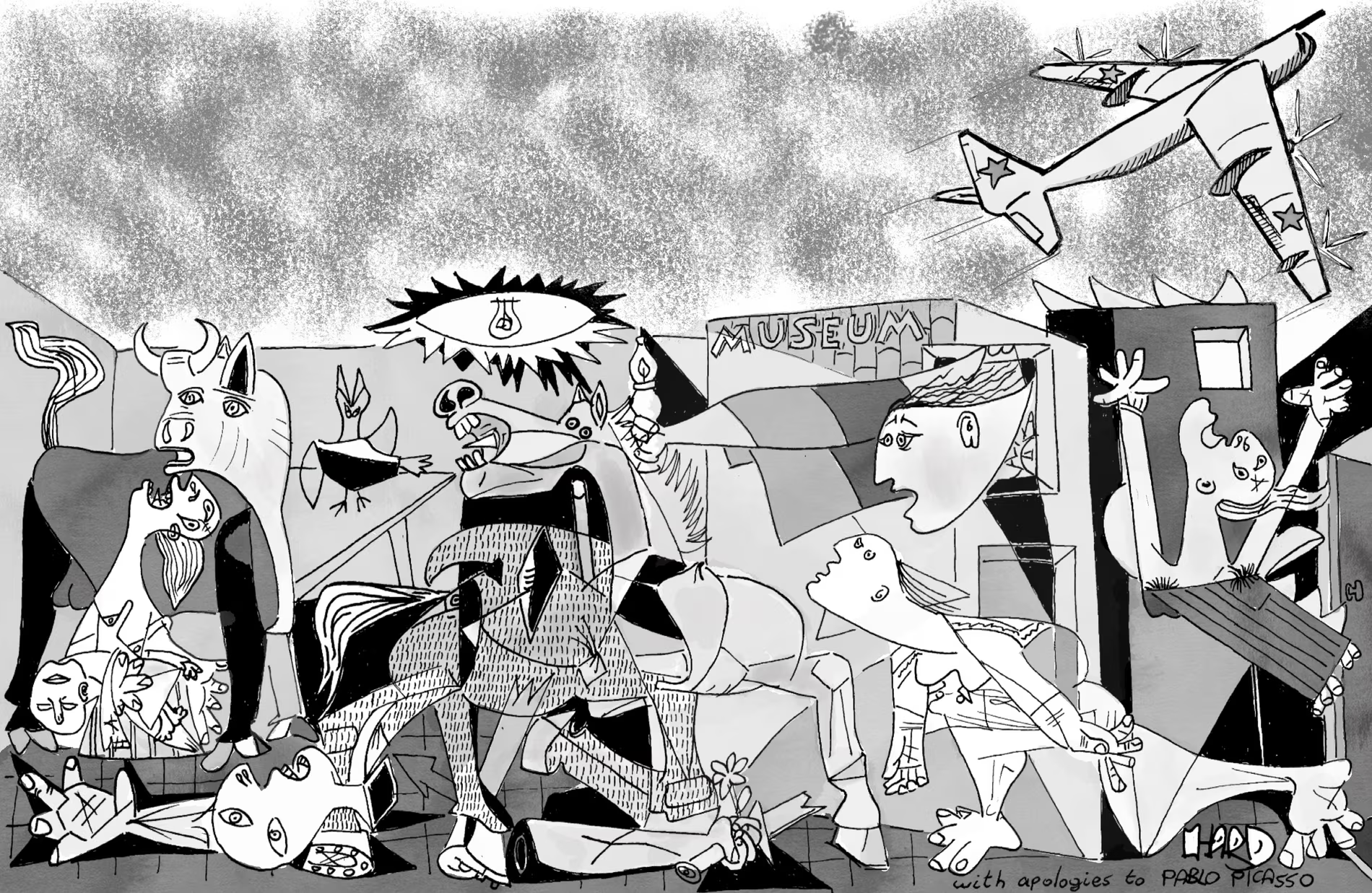

The shock of Picasso’s modern painting Guernica was recreated in 2016, by a graphic designer from Portugal, who drew “Alepponica,” a revised political cartoon about the battle for Aleppo in that year.

This artistic echo across time reflects how aerial bombardment of civilians has evolved as a distinctly modern form of warfare – where “modern” encompasses the mass-scale transformations that emerged from the 1500s onward. These changes gave rise to mass production, mass consumption, mass media, and mass transportation – and ultimately, weapons of mass destruction.

This modernity of mass destruction first revealed its full horror on April 26, 1937, when Nazi Germany attacked the Spanish city of Guernica. In a grim perversion of progress, civilian airliners were retrofitted with bomb bay doors, transforming vehicles designed for peaceful mass transit into instruments of warfare. Under the banner of Fascism, these aircraft carried industrial-scale weaponry to deliberately target civilian populations.

The attack on Guernica served as a rehearsal for the widespread bombing of civilian centers during World War II, most notably the German bombing of London during the Blitz. However, Hitler’s strategy proved counterproductive – rather than demoralizing the British population, the air raids strengthened their resolve to resist.

This historical pattern continues to repeat itself in contemporary conflicts. Russia’s targeting of urban centers in Syria and Ukraine follows the same flawed logic that guided the Nazi bombing campaigns. Like their predecessors, Russian strategists appear to believe that aerial bombardment will break civilian morale. Yet, as in Britain during WWII, these attacks have instead catalyzed defiance and resilience among the Syrian and Ukrainian people.

The shock of Picasso’s modern painting Guernica captures the disruption of civilians’ ontological security – that mental state derived from a sense of order and continuity in everyday life – when death comes from above. Throughout human history, civilians could at least see approaching threats: armies appearing on the horizon or ships entering a bay to lay siege or bombard urban centers. Picasso’s iconic painting depicts something new: civilians looking skyward in shock, among the first humans to witness death descending from above.

In the lobby of the United Nations General Assembly, a replica of Picasso’s mural hangs above the podium where international figures field questions from the media. It serves as a constant reminder to this multilateral body of the world community’s failure to act after Guernica in 1937 – a failure that led to World War II. By bearing witness, or in Arabic, being a “shahed” to Guernica and what it represents, UN diplomats would work to ensure such atrocities would not happen again.

Yet it did happen again. In February 2003, US Secretary of State Colin Powell, after delivering a presentation to the UN (holding a copy of the co-author’s plagiarized work on Iraq’s security services), refused to take questions in front of that mural, because such Guernicas would be repeated in Iraq more than a month later.

In 2016 Alepponica, the bull from Picasso’s painting is replaced by the head of Russian President Vladmir Putin, and a woman and her son underneath him fleeing Russian warplanes in the upper left.

Then later a Tupolev TU-95 bomber is inserted into Picasso’s painting, reconfigured as a political cartoon to accompany the Ukrainian writer Andrey Kurkov’s March 2022 Guardian article, “Putin’s bombs and missiles rain down, but he will never destroy Ukraine’s culture.”

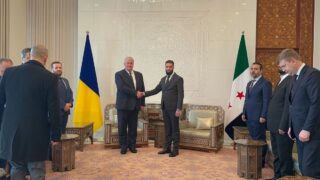

The neglected story of refugees is how desperate they are to return home. When it seemed by May 2022 that Russia could not take Kyiv, Maria left her life in Italy to make it back to Ukraine. Such yearning for home is universal – news reports have shown lines of Syrian refugees waiting at borders, hoping to return whenever conditions allow.

These modern displacements connect to deeper historical patterns. Timur-e Leng or Tamerlane was a Mongol chieftain who established a base in Uzbekistan, and his forces reached as far as Syria. They sacked Aleppo, and, like the events of December 2024, launched a lightning offensive that took the Syrian cities of Hama and Homs, until they reached the outskirts of Damascus.

Damascus capitulated to Timur without a battle in December 1400, with the Mamluk Sultan fleeing the city in disarray. (Ironically many of the Mamluks were slave warriors imported from Crimea). In the same month of December 2024, it was the al-Assad dynasty that collapsed without a battle, its leader fleeing to Russia.

The Turks call the Mediterranean the White Sea, and it is connected to the Black Sea and Red Sea. Indeed whether it is Spain or Syria on the White Sea, or Ukraine on the Black Sea, these lands have witnessed waves and histories of violence. The events in Syria demonstrate that there is hope that these waves can come to an end on the Black Sea as well.