Can Russia sustain its war effort as ruble plummets, inflation soars?

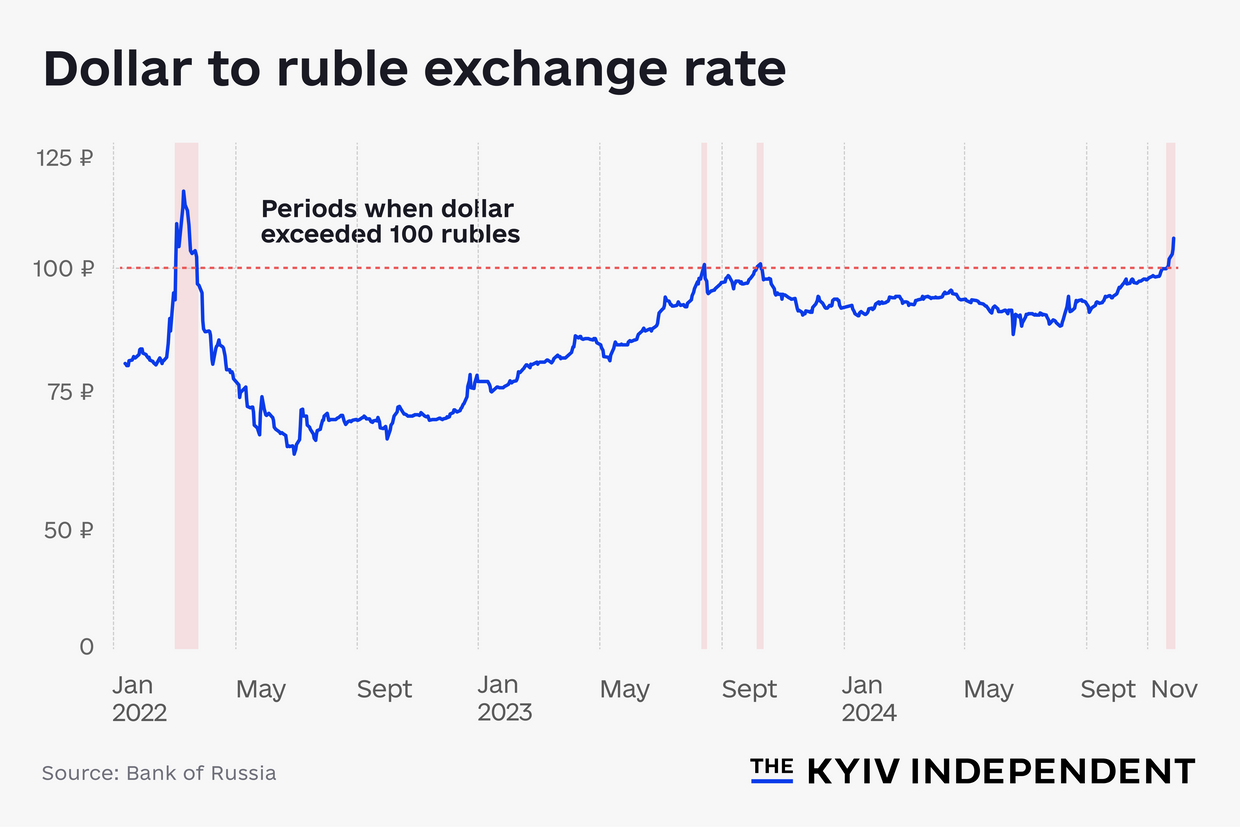

With the purchasing power of the Russian ruble hitting the lowest point since March 2022, the economic toll of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine becomes glaring.

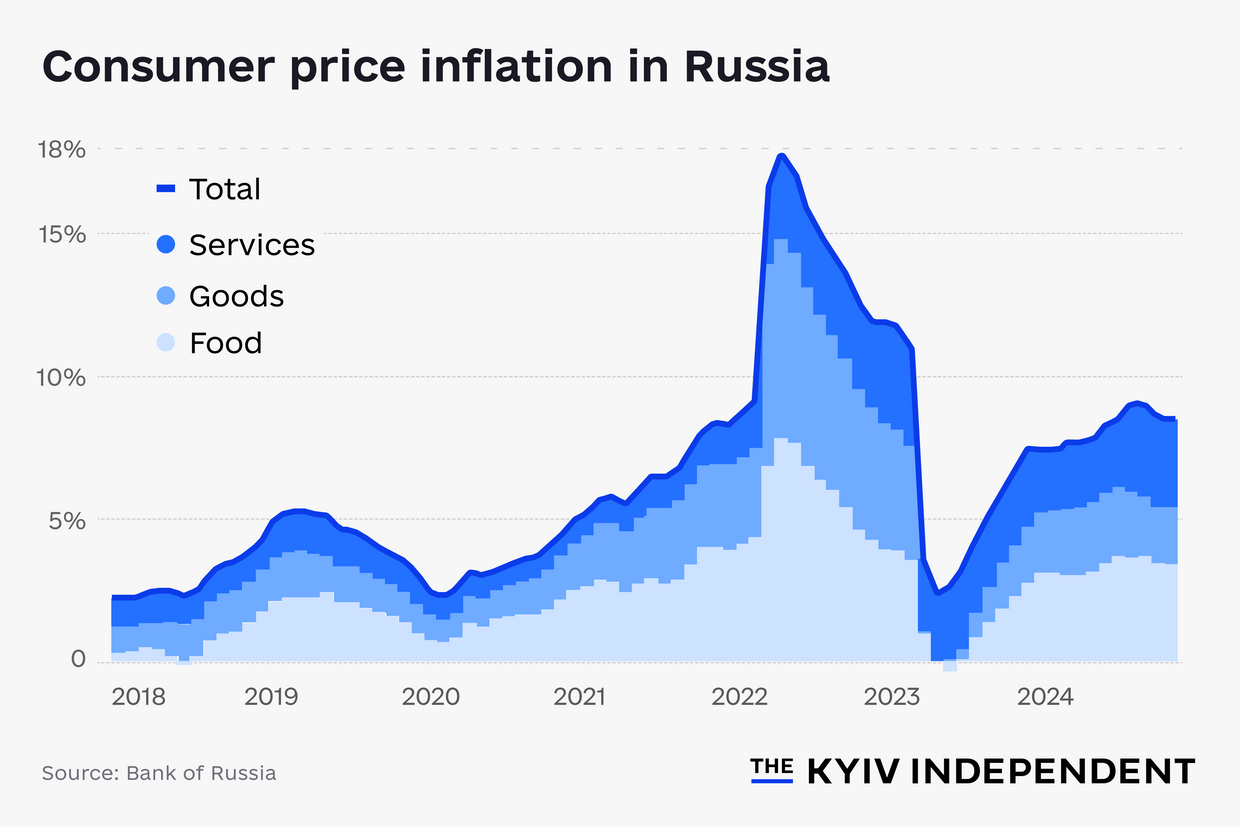

Russia's expanding spending on the war has fueled inflation, prompting Russia's Central Bank to hike its interest rate to the highest level since the early 2000s — 21 percent — to rein in consumer prices.

Inflation remained high regardless of the rate hike, speeding up to over 1 percent in the first three weeks of November and pushing the year-to-year numbers to over 8 percent.

In the wake of the economic challenges the country has faced over the past year, the U.S. government's Nov. 21 decision to impose new sanctions on dozens of Russian banks has proven hard for the country's economy to swallow.

"Russia is currently facing an impossible economic conundrum because of the rapid increase in military expenditures and the Western sanctions," Anders Aslund, a Swedish economist specializing in post-Soviet countries, told the Kyiv Independent.

However, economists and analysts are divided on how much of an impact Russia's economic problems will have on its war effort.

Some argue that it is becoming increasingly difficult for Russia to finance its war.

"Undaunted by economic reality, (Russian President Vladimir) Putin is raising defense and security costs to officially $176 billion in 2025, 41 percent of the federal budget expenditures," Aslund said.

"Yet, Russia can only finance 2 percent of GDP in budget deficit a year ($40 billion) because its only reserve is the National Wealth Fund," he said.

"At the end of March 2024, its liquid resources amounted to a mere $55 billion. Nobody lends money to Russia."

But others say that, despite all the economic difficulties, the Kremlin will have enough resources to finance the war for a long time at the expense of cutting spending on the country's civilian sector.

Sergei Aleksashenko, a Russian-born economist based in the U.S., said that "Putin's economic problems shouldn't be overestimated."

"He will spend as much money on the war as necessary," he said.

Even so, U.S. President-elect Donald Trump's team has shown openness to a potential plan to dramatically increase oil output and drive down oil prices, on which Russia's economy is heavily dependent. As a result, the Kremlin may be in for a bumpy ride.

"2025 will be a moment of truth," Vladimir Milov, a Russian opposition politician who was an economic advisor for the Russian government in the early 2000s, told the Kyiv Independent.

Central Bank between rock and hard place

Due to constant increases in military spending, Russia's budget deficit amounted to 3.2 trillion rubles ($30 billion) in 2023 and is expected to amount to 3.1 trillion rubles ($29 billion) in 2024.

Since 2023, inflation has been speeding up due to the same reason — from 2.3 percent year-on-year in April 2023 to 8.2 percent in November 2024.

Inflation contributed to the decreasing purchasing power of the ruble, which fell to 108 per dollar on Nov. 28, the lowest level since March 2022.

One of the latest blows to the ruble's value was the U.S. government's Nov. 21 decision to sanction dozens of Russian banks, including Gazprombank, which handles oil and gas payments.

To rein in accelerating inflation, Russia's Central Bank has been raising its interest rate — from 7.5 percent in July 2023 to 21 percent in October 2024.

The tight monetary policy of Elvira Nabiullina, the central bank's chief, has prompted a backlash from businesses, including those involved in the military industrial complex.

Sergei Chemezov, CEO of state-owned defense conglomerate Rostec, has lashed out at the Central Bank repeatedly.

"If we continue working this way, most enterprises will essentially go bankrupt," he said in October. "The question today is this: either we cease all high-tech exports — airplanes, air defense systems, ships, and so on, which require production timelines of a year or more — or we need to take some measures."

Opposition politician Milov said that Chemezov and Nabiullina "are both right" in their own way.

"Chemezov is right that businesses will have to shut down at such a (high interest) rate," he told the Kyiv Independent, "Nabiullina is right that the rate cannot be cut because in that case there will be hyperinflation like in Turkey."

He continued that "there is only one way out — finish the war and withdraw Russian troops" from Ukraine.

"Nabiullina is in a tough spot because of the spending on the war," Torbjörn Becker, director of the Stockholm Institute of Transition Economics and a co-author of a recent report on the Russian wartime economy, told the Kyiv Independent. "The whole war effort is creating a headache for Nabiullina. The military-industrial complex wants to spend more money. The military guys don't care about macroeconomic stability."

Is Russia headed for stagflation?

The Central Bank's policy of making credit more expensive may be contributing to a slowdown in economic growth.

Russia's gross domestic product rose 3.6 percent in 2023 amid a boom fueled by military spending, according to the State Statistics Service (RosStat). Russia's economy is expected to grow by 3.5-4 percent in 2024, but the growth is expected to slow down to 0.5-1.5 percent in 2025, according to Russia's Central Bank.

"There are no new investments, and the effectiveness of the fiscal stimulus is decreasing," Milov said. "(Economic growth) is also being killed by high inflation and the Central Bank's high rate. Credit is unbelievably expensive."

Milov believes that Russia's GDP may fall in 2025, and the country may experience stagflation — a combination of stagnation and high inflation.

Alexandra Prokopenko, an economic expert at the Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center, argued that "it's not stagflation yet, but Russia is close."

"Recent data suggests that the overheated Russian economy is starting to cool," she told the Kyiv Independent. "This includes a fall in retail lending, slowing wage increases, and dropping industrial growth. However, it shouldn't be overstated. Despite the signs of cooling, the fundamental drivers of overheating remain in place — growing military production and an intense labor shortage."

"Recent data suggests that the overheated Russian economy is starting to cool."

She added that "in some sectors related to the military (like, for example, finished metal products and optics and computers), there is no sign of any cooling."

Yulia Pavytska, an economic expert at the Kyiv School of Economics' think-tank, KSE Institute, told the Kyiv Independent that "the current policy of the Russian Central Bank will either lead to stagnation — the absence of economic growth — or the regulator will fail, in which case inflation will continue to rise."

She added, however, that "a combination of stagnation and inflation is currently an unlikely scenario, given the continued fiscal stimulus in the form of war-related expenditures and the significant labor market deficit."

Aleksashenko said that he did not expect a drop in Russia's GDP in 2025. He told the Kyiv Independent that labor market shortages were slowing down economic growth but their impact was relatively small.

Higher inflation on the horizon?

Some analysts predict that pressure from industry, including the military-industrial complex, will lead to Nabiullina's downfall.

"Putin understands that Nabiullina is useful but there is more and more pressure from security forces," Russian political analyst Dmitry Oreshkin told the Kyiv Independent. "In this struggle, the military-industrial complex will inevitably win because Putin is waging a war."

Aslund agreed, saying that "Chemezov and other industrialists will oust her very soon and make the correct point that high interest rates solve none of the (Central Bank's) tasks, which would be correct, but they will push for lower interest rates, which will aggravate the situation."

"Inflation will rise, the capital outflow will accelerate, and the exchange rate will fall," he told the Kyiv Independent.

Aslund also said that he "would not suggest hyperinflation (over 50 percent increase a month) but a substantial increase in inflation, which will cause popular dissatisfaction."

Andrei Movchan, a Russian-born economist and founder of Movchan's Group, told the Kyiv Independent that, if the Central Bank changes its policy and cuts its rate by several percentage points, inflation could rise to 20-25 percent but it would not lead to a "catastrophe" or "destruction of the economy."

Stay warm with Ukrainian traditions this winter.

Shop our seasonal merch collection.

const stayWarmWithUkrainian = document.getElementById(“stay_warm_with_ukrainian__snippet__link”);

stayWarmWithUkrainian.addEventListener(“click”, () => {

window.dataLayer?.push({

event: `InternalLinkClick`,

element_category: “Snippet”,

element_name: “E-store-christmas”,

target_url: “https://store.kyivindependent.com/collections/winter-collection”,

target_text: “Shop Now”,

});

});

War effort unsustainable?

Although economists agree that Russia is experiencing economic difficulties, they are split on whether they will make its war effort unsustainable.

Aslund said that "Russia's macroeconomic failures will become a critical factor next year, perhaps rather soon, though these things are always difficult to time."

Anders Olofsgård, a deputy director at the Stockholm Institute of Transition Economics, shares these thoughts.

He told the Kyiv Independent that "it is becoming increasingly expensive for Russia to finance the war, with domestic military production at capacity, inflation and wages surging, and them increasingly turning to allies such as Iran and North Korea for military equipment and even soldiers."

"They are also gradually depleting the external reserves they have, and the worse the economic situation, the more they need to turn to those reserves to afford the expansion in military expenditures," he said. "Unfortunately, this doesn't mean that they will run out of money tomorrow, but depending on oil and gas prices, the effectiveness and enforcement of sanctions, and the competence and credibility of their macroeconomic policies, that day is coming."

Milov said that there is less and less money at Russia's Federal Wealth Fund, and it's difficult for the government to borrow at such a high interest rate.

The government has tried to raise money by increasing taxes but the "tax hikes will accelerate the slowing down of the economy and reduce the tax base," Milov continued.

"They'll have to decide something because they can't wage such a high-intensity war anymore," he added.

Milov said that the production of more primitive military products — such as drones, bombs, and artillery shells — is expanding. However, it is more difficult for Russia to produce more complex equipment — tanks, armored vehicles and aircraft, he added.

"They'll have to decide something because they can't wage such a high-intensity war anymore."

Other economists are more cautious.

"Russia is currently not facing serious fiscal challenges," Pavytska said. "It is likely that the Finance Ministry will be able to execute this year's budget as planned."

She said that domestic borrowing would be "costly," but the government would take this step if needed because "the regime needs money for the war now, not in some abstract future."

"In modern Russian realities, the key interest rate is, de facto, irrelevant to the regime," Pavytska added. "Funds for the war will be found in any case, including by cutting other expenditures, as evidenced by the draft budget for next year, or through monetary issuance."

Movchan and Aleksashenko said that the defense sector gets direct funding from the budget, not loans, and it would be funded regardless of high interest rates. They argued that Russia's economic difficulties were not affecting its war effort.

Movchan said that Russia would start experiencing problems with funding the war only if oil prices fell significantly, leading to a major drop in the government's foreign currency earnings. He added, however, that he believed that a major fall in oil prices was unlikely in the near future.

The hope for a drop in oil prices was boosted recently by Trump's plan to issue more permits to drastically increase U.S. oil and liquefied natural gas production. Reuters reported on Nov. 25 that Trump's transition team was working on the plan and would roll it out within days of him taking office in January.

Oreshkin said that Russia's current economic turmoil is unlikely to strengthen Ukraine's hand in potential peace talks. But, if Trump manages to drive down oil prices and cracks down on Russia's evasion of oil sanctions, Ukraine will have a stronger position, he added.