Biden was “killing Ukraine softly.” Trump won’t wait

As Donald Trump is set to become the US President in January, critical questions loom about the future of Western support to Ukraine in its war with Russia.

Trump’s repeated claims about achieving a “quick end to the war” have raised concerns about potential pressure on Ukraine to make territorial concessions, even as the country enters its third year of resistance against Russian aggression.

What can this “quick end to the war” mean for Ukraine? What does Ukraine need to prevent simple capitulation to Russia after 3 years of fighting? Is returning to the Ukrainian borders of 1991 still a feasible goal?

Against this backdrop of uncertainty, several crucial issues demand attention: the continued restrictions on long-range strikes with Western weapons, persistent fears of escalation (present even in Trump’s team) and Russia’s potential collapse, and Europe’s relative passivity in regional security matters.

We discussed these pressing questions with Alyona Getmanchuk, founder and director of the New Europe Center think tank and non-resident senior analyst of the Eurasian Center of the Atlantic Council (USA).

Getmanchuk analyzes how Ukraine should approach Trump’s presidency and introduces an innovative concept of a “Coalition of the Resolute” – a new framework for European military involvement that could serve as a security guarantee amid unpredictable Trump-Putin peace negotiations.

“Killing Ukraine softly:” measured US support led to slow defeat

EP: How do you assess the current level of US support for Ukraine?

The Biden administration helped us survive, and we will always be grateful for this. But we must also understand that the current administration’s policy of “as long as it takes” has failed. By pursuing it, we can’t achieve what we in Ukraine would consider our victory. “Ukraine is still free” is not a victorious strategy.

US support wasn’t aimed at helping Ukraine regain its lost lands and recently also proved to be insufficient for the proper level of defense. Instead, this support was designed to help Ukraine avoid state collapse while simultaneously preventing the United States from becoming part of a direct confrontation with Russia.

This led to Ukraine’s slow defeat, not victory. It was a policy of measured support. There is a song, “Killing Me Softly.” Biden’s policy was “Killing Ukraine Softly,” so to speak.

EP: There is an opinion that the primary factor that prevents the US establishment from going all-in on Russia and supporting a Ukrainian victory is their fear of Russia falling apart, and the unpredictability that this brings. Do you agree with this assessment?

I’ve heard this argument in the major Western capitals that are paralyzed by fear the most—Washington, but especially Berlin. They are still inclined to see things through the lens of their understanding of what developments create more destabilization. And from their view, even ill-freezing a war in Ukraine is a less destabilizing factor than a potential Russian collapse.

“Ukraine is still free” is not a victorious strategy.

EP: Do you think the USA’s fears of escalation with Russia are justified?

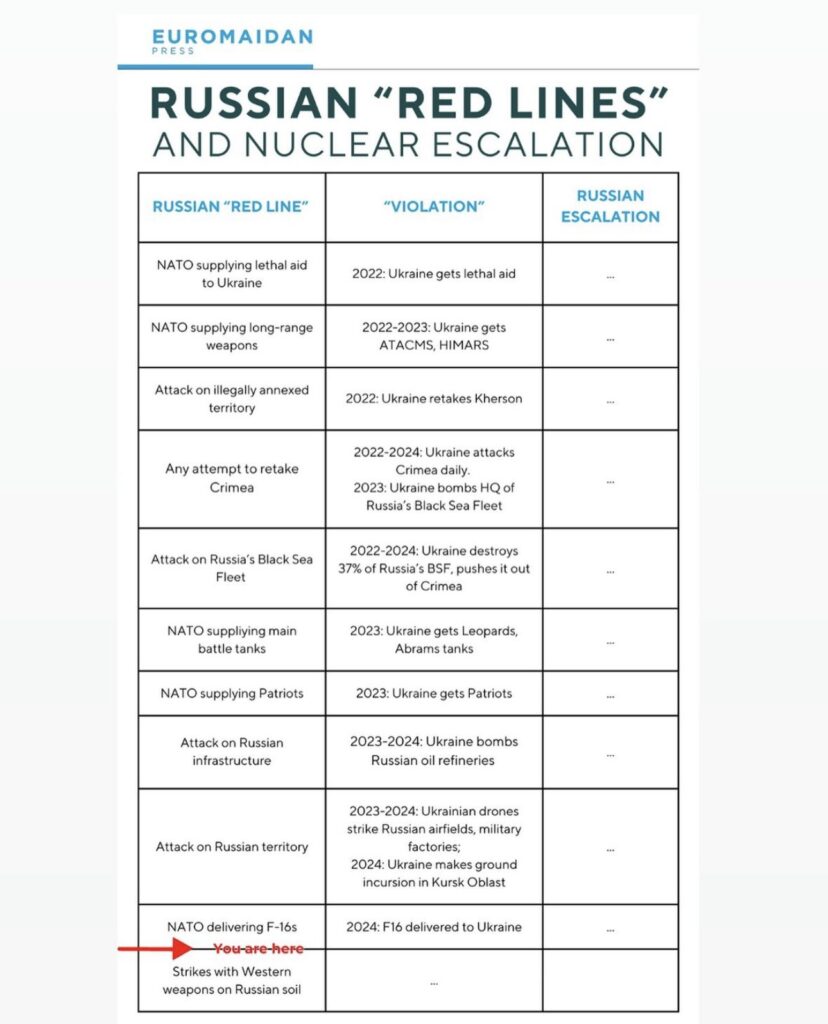

There is always ground for concern about Putin’s Russia. But looking back from 2.5 years of war, it’s obvious these fears were exaggerated, hyperbolized, and effectively paralyzed the White House in swiftly making critically important decisions for Ukraine.

Decisions that could have been made long ago and could have helped Ukraine change the course of the war in Ukraine’s favor still haven’t been made. For instance, deep strikes with Western long-range weapons still have not been greenlighted, even now, after the presidential election.

Prior to the election, there was a fear of escalation mixed with a fear of Donald Trump being elected president when a number of steps were postponed in order not to give Republican candidate arguments strengthening his already strong narratives that Biden’s Administration is dragging the US into III World War and nuclear confrontation with Russia. This thunderous mixture of two fears created even more problems for Ukraine in getting important for our defense – not Ukraine’s counter-offensive actions – decisions approved.

Western fears of escalation only benefits Russia

EP: Regarding long-range weapons strikes, do you think the Trump administration will take a braver position or a more restrained position on this?

First, we need to keep convincing the current administration to approve this decision because the fear of Trump’s election has been removed. During the campaign, Biden didn’t want to give Trump’s arguments that the Biden-Harris administration was drawing the United States into World War III and nuclear confrontation with Russia any support. Now that rationale is gone.

But I think there are also prospects for such approval under the Trump administration if, for example, there’s a feeling that a decision like this one will make Putin more eager to negotiate even without a list of preconditions.

Today, when his offensive in Ukraine continues, it seems that he has no special interest or special motivation to go into such negotiations, so it’s necessary to boost his appetite for negotiations by adopting strong and bold decisions. But as Ukrainians, we need this decision primarily from the defensive point of view – to minimize the number of attacks on Ukraine. Air defense capabilities are extremely important, but they are like painkillers. We need to target “sources of pain.”

Even though, right now, we don’t know if the future Trump administration will be also driven, if not paralyzed, by a fear of escalation. I have an impression based on Trump and his entourage’s statements that they are also obsessed with the idea of avoiding World War III by not respecting Putin’s red lines, but we don’t know whether these statements will convert into practical restrictions on certain types of weapons, etc.

It’s important to convey a message that nothing helps to transform the Russia-Ukraine war into a global war more effectively than a policy aimed at demonstrative avoidance of escalation with Putin, respect for his “red lines,” slow response in decisions and actions which only vaccinate Russia, providing it’s time to adopt to new developments and request help from China, North Korea, Iran.

Trump’s “quick deal” approach poses risks of pressuring Ukraine into unacceptable concessions

EP: So is there a possibility for the Trump administration to also be quite indecisive, especially regarding permission for long-range weapons, for example, even despite Trump’s bold statements that he’ll end the war quickly?

At this early stage, I would risk saying that Trump’s decisions will be made faster because Democratic administrations in the US generally tend to overthink things, which makes them slower at their decision-making. The Biden administration did this in a very concentrated form.

But I see signals that Trump’s team also has a strong unwillingness to provoke a direct confrontation with Russia.

Trump promised to end all wars and not start new ones. His campaign rhetoric on this sounds very attractive to American voters, but if we’re talking about short-term prospects, not everything depends exclusively on Donald Trump and his desire to end – or rather suspend – the war in Ukraine as quickly as possible, however masterful he might be.

Biden also promised to end wars during his election campaign, and he did end the war in Afghanistan, but not in a way that is really positive for his presidential legacy. And we see that new wars started instead.

EP: Trump has repeatedly claimed he could end the war in Ukraine quickly, even within 24 hours of taking office, though he has not provided specific details on how he would achieve this. Some analysts claim this might involve pressuring Ukraine to make territorial concessions. What risks do Trump’s statements about negotiations with Russia and relations with Putin pose for Ukraine?

The very concept of a quick deal itself poses risks, because such a deal is hardly possible without pressuring Ukraine to make unacceptable concessions, especially as Ukraine depends greatly on financial and military support from the West.

But Trump also talked about a fair deal. I think we need to explain that it’s more important to stick specifically to a fair deal—not only for Ukraine but also for him and his presidency.

Trump wants to conclude this deal and suspend the war at the beginning of his cadence, which has both pros and cons.

The con is that if this deal turns into a de facto capitulation of Ukraine, with the satisfaction of Putin’s demands and without real security guarantees for Kyiv, there might be a new war very soon, still during Trump’s presidency. In that case, Trump will be forced to deal with an even more massive war, and maybe not only against Ukraine but also against other countries in the region.

Any ill-cooked deal might look as if Ukraine was actually given up to Putin, and Trump personally will look like a person who handed Putin victory in the war and helped him rebuild the new Russian empire. Or Soviet Union 2.0, you name it.

Then, this won’t be a deal that could bring Trump the glory of being a Great Peacemaker or recognition that would allow him to be nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize, for example.

Any ill-cooked deal might look as if Ukraine was actually given up to Putin, and Trump personally will look like a person who handed Putin victory in the war and helped him rebuild the new Russian empire.

Trump prefers transactional relationships over donor-recipient models

EP: Trump made statements criticizing American financial aid to Ukraine. If this aid drops or ceases, what role will European allies play?

There are several aspects here. First, Trump is generally critical of donor-recipient models of interaction with other countries. He views things more through the prism of business relationships or seller-customer relationships. Therefore, we need to look for other models of interacting with his administration that are more transactional.

Second, many Republicans reject financial aid that supports the Ukrainian budget and state employees but are positive towards military aid and delivering weapons to Ukraine. So if general aid gets slashed, perhaps military aid will remain.

Nearly all ideas on ending the war from Trump’s team representatives floated in world media foresee Ukraine continuing to receive weapons and military aid to repel possible sudden new attacks from Russia. The question is whether the Trump team views this aid as coming exclusively from European countries or also from America.

A win-win solution for further maintaining military aid would be if the majority of the funds allocated to Ukraine’s defense would go to purchasing American weapons, supporting production and jobs in the USA, but a part would also be used to buy Ukrainian-produced weapons.

The main thing that worries many Republicans is that with donations to the Ukrainian budget, the check keeps growing, but this doesn’t change the course of the war.

If Ukraine explained that it needs a specific sum to achieve specific results, which could also accelerate meaningful talks, I think this would change the course of the discussion.

Currently, many, not only in the Republican party but in American society in general, feel that Ukraine is becoming another forever war — one where funds are allocated, but there is absolutely no sign of ending the war.

Time for Europe’s “security vacation” to end as Trump comes into office

Regarding our European partners, I hope that Trump’s election will give them more understanding that Europe’s security is, first of all, Europe’s responsibility.

This is very difficult to recognize because, for half a century, European countries were on “defense and security vacation” under the “ umbrella” of the United States.

Actually, Trump’s first presidency should have been a wake-up call for Europeans. They should have started doing something then. Russia’s full-scale invasion should have been the wake-up cry for them.

But we see that some European countries, until election day, hoped that Kamala Harris would become president and everything would continue by inertia.

They behaved as if it was not necessary to accelerate their own defense production and demonstrate more leadership in taking care of European security. I hope that the second Trump presidency will play the role of this wake-up cry, not even a wake-up call anymore.

Plus, there’s a new factor: Ukraine as an EU candidate. This means that we share responsibility for European security, and similarly, the European Union should share responsibility for Ukraine’s future. I hope Trump’s presidency will accelerate the emergence of a “coalition of the resolute,” a coalition of countries that understand the price of Ukraine’s defeat and the price of a bad deal regarding Ukraine during Trump’s presidency.

They understand that such a bad deal for Ukraine is also a bad deal for Europe’s security.

Some of these countries could be important contributors to financial aid, and others could contribute military components to protect us during the vulnerable phase of potential suspension of the war. Yet others could be ready to create an Air Defense Shield over Ukraine.

This means that we share responsibility for European security, and similarly, the European Union should share responsibility for Ukraine’s future.

EP: This coalition is not NATO, but something new, right? So far, we have seen no such resoluteness or involvement from NATO.

These are NATO member countries, but NATO’s hands are sometimes tied by a need to reach a consensus, just like the EU. They include both countries that support Ukraine and understand that Putin is waging a war not only in Europe but also against Europe, but also others that indirectly motivate Russia to continue its war by helping circumvent sanctions, undermining important decisions regarding Ukraine, or proposing some ideas of diplomatic settlement which similarly only encourage Putin to stick to his aggressive plans.

Zelenskyy’s plan should not “compete” with Trump’s ideas

EP: Zelenskyy presented a victory plan for Ukraine’s partners, but many media wrote that it wasn’t received with much enthusiasm. What was missing? How should this communication be changed?

There was a sort of ping-pong game when Republicans said they were waiting for the Biden administration to present Ukraine’s victory strategy before providing new aid. And the White House pointed at President Zelenskyy as the one who should determine this strategy first.

It wasn’t received so well, but this is not Zelenskyy’s problem, as he provided the plan.

Why wasn’t it liked? Maybe there were expectations that it would be more of a ceasefire plan with a clearly envisaged phase of “freezing” a war. But there’s no element of ceasefire in this plan.

We understand that Washington and many people in both parties are skeptical about Ukraine being able to win the war by military means and return to the borders of 1991. Leading figures in both parties mainly consider these Ukrainian goals unrealistic.

But this plan doesn’t say that by executing it, Ukraine will return to the borders of 1991 immediately or uninterruptedly. We actually explain with this plan that we need to change the course of war in Ukraine’s favor and force Putin to sit at the negotiating table, but not at the table where Ukraine’s “unconditional capitulation,” as Russian decision-makers put it, will be signed.

The clear difference between Trump and Biden is that Trump believes and openly shows that he should be the initiator of negotiations, not Zelenskyy.

The Biden administration constantly insisted that Ukraine and Zelenskyy should initiate the negotiations. Trump immediately made clear that he views himself as this initiator, as a person who wants to resolve the war and enter history.

For Zelenskyy, it’s important that his plan wouldn’t be perceived by Trump as some competitive idea.

If the Biden administration had expected exactly a plan from Zelenskyy, it could now have been seen as a competing proposal. We understand how Trump reacts to such things, and need to think about how to integrate ideas from our plan as well as the Peace Formula into Trump’s peace proposal.

Trump believes and openly shows that he should be the initiator of negotiations, not Zelenskyy.

Now the key task is to change the course of war in Ukraine’s favor or, at least, strengthen the positions of Ukraine. The majority of the plan’s points are about strengthening its positions and must be viewed in a complex way; you can’t pull them out as separate points. Only taken together do they give an understanding of how Ukraine can end the war if not in our complete interpretation of victory, then at least with a suspension that is advantageous for Ukraine.

Because both in Trump’s administration, or, for example, if Harris was elected, the discussion would still be about suspending the war, and not actually supporting and helping the USA to liberate all Ukrainian territories and return to the 1991 borders.

Security guarantees for Ukraine crucial to prevent future wars

EP: So, as in Trump’s statements, there are no narratives about the exact return to the borders of 1991, right?

For example, Trump’s surroundings talk about freezing the war with a demilitarized zone. The Biden administration discussed a negotiated settlement. However, this was also de facto about freezing, just called another way.

However, for Ukraine, real security guarantees are the fundamental question. We need to explain why it is important for us not to freeze the issues of NATO invitation and membership but, on the contrary – maximally unfreeze and accelerate this process. We need this to avoid new Russian wars not only for the next two years, but forever because Ukraine’s membership in NATO is the most powerful signal for Putin, Russian elites, and for Russian society that Ukraine won’t be part of the Russian Empire again, that Ukraine is an irreversible part of the West.

“Coalition of the Resolute” could include military presence in Ukraine for security

EP: So now besides NATO membership, Ukraine also needs a creation of this new “coalition of resolute”?

This is the position of the New Europe Center – the idea which we call “coalition of resolute.” It envisages decisive actions, including the deployment of troops.

But the main idea is that security guarantees should be a precondition for any “talks about the talks,” not a part of negotiated settlement.

I believe a part of these security guarantees should actually be the military presence of European countries, this “coalition of the resolute” in Ukraine along the contact line or administrative line, which will be determined during possible negotiated settlement.

Trump’s team shows a much larger appetite for this scenario than there was in Biden’s team.

Trump’s team talks much more about the military mission of Europeans, and this is already a substantial step forward on this issue because the Biden administration did not show a desire to involve Europeans more. This was viewed as an escalation of incredible scale.

However, we will continue pushing for European and American security guarantees, preferably through NATO.

Ukraine’s membership in NATO is the most powerful signal for Putin, Russian elites, and for Russian society that Ukraine won’t be part of the Russian Empire again, that Ukraine is irreversible part of the West.

EP: And how can the fact that Donald Trump has relations with Putin and talks about his ability to negotiate with him influence Ukraine and the peace talks?

Of course, it would be good to end the war without the direct involvement of Putin, but indirectly forcing Putin by proper actions to stop the aggression,

However, even Zelenskyy and the Ukrainian authorities admitted that representatives of Russia could be present at the second Peace Summit. Yes, maybe not Putin personally, but representatives of Russia.

We cannot forbid Donald Trump from talking with Putin. Similarly, we cannot teach him how to talk with Putin.

I’m not overdramatizing talking about Ukraine without Ukraine. I strongly condemn making decisions on Ukraine without Ukraine. That’s the biggest risk we should avoid. Also, we need to maximally involve important European countries so that they are at the table of any negotiated settlement.

So that this wouldn’t be an agreement, conditionally speaking, between the USA and Russia, but it would also involve Europeans. Which is logical because it’s primarily about European security.

And here, this “coalition of the resolute”—including the UK, France, Northern Europeans, Baltic countries, and some Central European states—could take on significant responsibility. We must prevent any peace negotiations from being monopolized exclusively by Putin and Trump.

Related: